After many a summer, the swan gets cluster-bombed

How should we think about the European war as it enters its second summer? It sometimes seems, for those of us on the Left, that we are caught among the weeds of a great many traditions of war thought: scepticism about the military-industrial complex; support for the self-determination of invaded states; dislike of dictatorship; fear of nuclear war; commitment to international justice; and a sense that this justice is asymmetrically applied and enforced. There is, perhaps, at times either a forgivable paralysis or outright confusion.

Meanwhile the British (and Anglo-Australian) commentariat and political classes are in the grip of an unwavering consensus. Virtually everyone is now in favour of the war. As Paul Fussell said of a previous European conflict, ‘the war kept winning’.

Or at least a particular version of the war keeps winning. It goes something like this. On 24 February 2022, the Russian state and Vladimir Putin launched a wholly unprovoked war on a democratic sovereign state and its pro-Western populace. This war is a crime of aggression and an assault on what Australian officialdom likes to call the ‘rules-based global order’, and it has been accompanied by the very worst war crimes and crimes against humanity. The only possible ending to this war will be the comprehensive defeat of Russia—possibly even its disintegration—followed by the restoration of full Ukrainian territorial integrity, the removal from office and trial of Vladimir Putin, and the launching of a series of war crimes proceedings against many of his officers and soldiers. The relevant analogy is 1938 and the disastrous appeasement at Munich. Unless Russian military capabilities are destroyed, Poland or Estonia or Sweden will be next in Putin’s sights (this is the latest iteration of the periodically discredited ‘domino effect’). This common position involves a mixture of the operatic, with good and evil carefully demarcated, and the historically contingent. Iraq is barely mentioned. Gordon Brown has proposed a special tribunal to charge the Russians with a crime of aggression, with all thoughts of his own involvement in a 2003 crime of aggression dismissed from the picture. In a panel I was on recently—and these panels seem to be largely about denouncing the Russians—a fellow panellist called for Russia to be expelled from the international system ‘forever’.

Forever?

It’s not as if this is all nonsense. Under international law the Russian invasion is an act of aggression. The Ukrainian state and the Ukrainian people have been the victims of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The situation for ordinary civilians, for soldiers, for families facing daily bombardments and all manner of shortages and privations is appalling.

In this feverish atmosphere, it’s not easy for anything heterodox or even—1938 apart—historical to be given much of a hearing. But other perspectives are possible, and my aim in offering this particular counterpoint is to help us to begin thinking about ending the war in a way that might save the lives of thousands of Ukrainians and Russians.

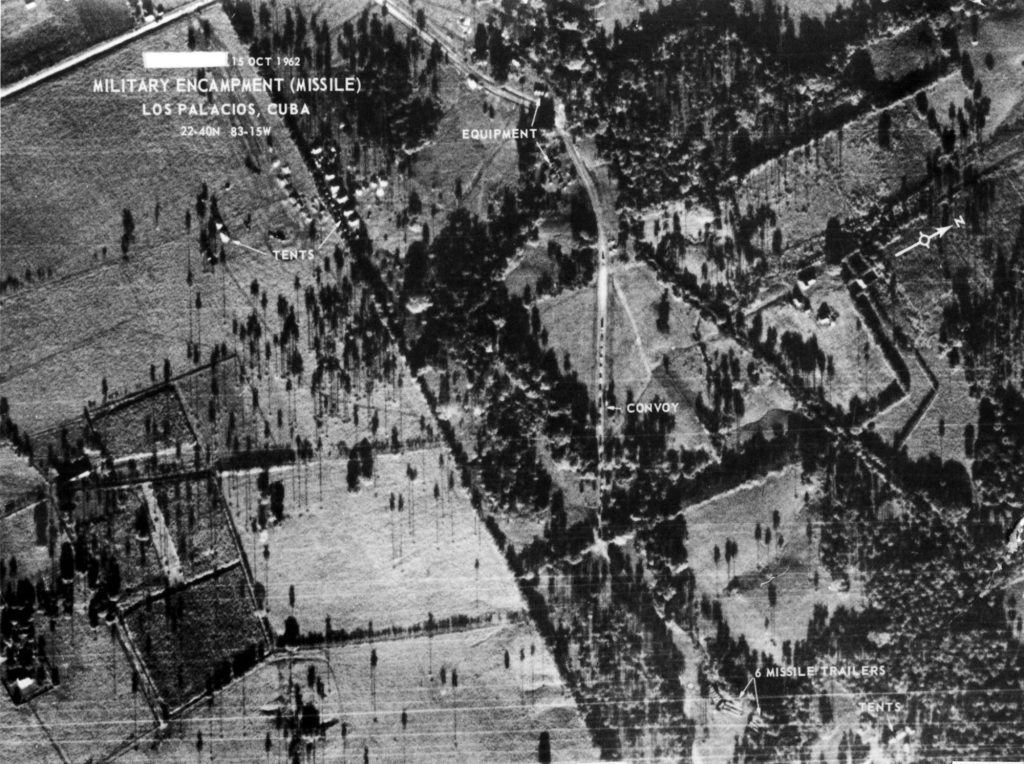

At an event in Sydney this year I mentioned some parallels with the Cuban Missile Crisis, and was told that this was exactly the comparison Putin wanted us to draw. To argue against the war or to speak about it in a different register is to become Putin. And yet the October Crisis, for example, might be a useful analogue. For Vladimir Putin read John F, Kennedy; for Fidel Castro read Volodymyr Zelenskyy. In 1962 Kennedy was unwilling to accept a rival power in the US sphere of influence. Of course, the United States did not quite invade Cuba—or if it did, its attempt at the Bay of Pigs was, rather like the Russian war on the Donbas in 2014, merely the beginning of a long subversion of a sovereign state. But Kennedy made it clear that the United States would not tolerate an enemy on its doorstep, and certainly not a heavily armed de facto Warsaw Pact member. Castro, meanwhile, was agitating for a world war over Cuban sovereignty, even it this meant the end of Cuba itself. This would have marked the final displacement of material sovereignty by its pure form, sovereign as sign. Cuban sovereignty would be preserved at the cost of Cuba’s existence.

The parallels are striking (and, as always, imperfect): the Zelenskyy-Castro figure prodding his patrons into a wider war; the Putin-Kennedy figure refusing to tolerate a radical rearrangement of geographical spheres of influence; the destruction of the Donbas-Cuba necessary in order that it be saved. Of course, these historical comparators are rarely mentioned, the focus being relentlessly on appeasement and 1938.

For this 1938 idea to work, though, the Russian threat has to be exaggerated, as military threats nearly always are (for the Russian Army in 2022–23 see the Republican Guard in 2003 or the Red Army in 1968). Remember the missile gap? So on the one hand, we are warned that NATO’s eastern flank is threatened; on the other, we are reassured that the Russian Army would be obliterated by the North Atlanticists within three or four days. But this latest Putin War, following on from Georgia in 2008 and Crimea in 2014, is surely more likely to be his last major intervention. Ukraine is his Iraq: a war that ends a particular kind of annexationist military adventurism for two decades at least, if not more.

This kind of counter-narrative does not suit the popular imagination, the war-gripped media and the gleefully righteous political classes. ‘The Russian threat’—an atavistic trope that almost constitutes Western European identity—is back.

Donald Trump, in one of those moments where disinhibition meets idiot savant diplomatic intelligence, asked several years ago what the point of NATO was. Russia has now supplied a point, but it would be ahistorical not to point out that this threat is also partly an affect of NATO strategy since the end of the Cold War. As many people have been pointing out recently, it was long predicted that an eastward expansion would invite war. In 2007, fifty foreign policy experts wrote to Bill Clinton opposing NATO’s enlarging membership and describing it as ‘a policy error of historic proportions’. In 1988 George Kennan, in The New York Times, called NATO expansion a ‘tragic mistake’. Anyone who has studied Great Power politics will have been aware of the risks of moving an aggressive and hostile security organisation up to the Russian border.

Again, the dominant narrative dismisses this kind of talk as ‘history’ or ‘excuse’, as if it is not possible to condemn the Russian invasion, analyse its deeper historical roots and seek an end to the war all at the same time. And there is a parallel blindness when it comes to the conduct of the war. This is regulated in international law by the laws of war, or international humanitarian law to give it its softer designation, and it is an important and necessary principle of this legal regime that it does not have anything to say about the justness or overall lawfulness of the war itself—that is, its status as a war of self-defence or an illegal invasion. All protagonists are treated alike.

There is always a certain pressure on this idea when the West is at war. Our war crimes are mistakes, or the result of agonising moral and strategic calculations; the enemy merely displays a brutal disregard for these laws. There is little doubt that Russia’s invasion has been accompanied by the most vicious war crimes; nor is there much doubt that less pervasive Ukrainian violations are likely to be underreported. But it is striking how forgetful we are in talking about and condemning such crimes. The British press and political class were aghast when reports began to emerge about the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam. What sort of state blows up a dam as an act of war? Rishi Sunak called this ‘a new low’.

It turned out to be a rather old low.

Opposite the Australian High Commission in London is a statute of Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, the man who invented and implemented the air assault on German dams towards the end of the Second World War. This brilliant piece of military strategy, or war crime, has been celebrated in British cultural life in film (The Dam Busters) and in music (‘The Dam Busters March’). I don’t recall any mention of this a few weeks ago as commentators fell over themselves to deplore Putin’s dam-busting ghastliness. Indeed, The Sunday Times, whose sister paper quickly described the attack as a ‘war crime’, today rated The Dam Busters—‘a story of triumph against the odds … one of the most daring missions of the Second World War … authentic British heroism’—the third finest war film ever made. We do not have to deny that the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the war against Nazism are very different types of wars to find these parallels disquieting.

What kind of state uses cluster weapons? Only the most despicable, surely? On 22 February 2022, the US Envoy to the United Nations, Linda Greenfield, accused Russia of using cluster munitions ‘which are banned under the Geneva Conventions … and have no place on the battlefield’. Over 100 countries have indeed prohibited their use. The United States would never sanction their deployment…unless it was militarily necessary or desirable. So we have the unusual sight of the United Kingdom and the United States in disagreement over the transfer of such weapons to the Ukrainians. The Biden Administration, not insensible to the broader historical context in this war, made the ‘difficult’ decision to send these weapons—a byword for war crimes—to Ukraine. Accompanying these weaponised droplets were the familiar justifications: the Ukrainians will be using them on their own territory; they are modified cluster weapons; the Russians are already using them; it’s temporary.

Jens Stoltenberg, early in 2022, characterised the early Russian deployment of cluster weapons as a ‘violation of international law’. He went on to say at the time that he welcomed the decision of the International Criminal Court to begin an investigation into their use. There was no such talk of war crimes last week at a Stoltenberg press conference, where it turned out that NATO didn’t have a formal position on the use of cluster munitions and that it was for individual allies to make decisions about transferring them to the Ukrainians. All the while, the Russian bombing of Ukrainian infrastructure is reported by the BBC with the kind of intonation that strongly suggests that each and every one of these attacks is a war crime.

A. J. P. Taylor once said that states don’t commit crimes, they make mistakes. Surely it’s time for an amendment? We make mistakes; they commit crimes.

None of this excuses Russia’s invasion, or its methods of war-making, each if which is deplorable by any measure. But this historical context and some awareness of our own flexible standards will be vital as we think about how to achieve a settlement with the Russian state.i There have been some encouraging signs. In recent weeks, news media have reported some overtures (former US officials in conversation with Lavrov; CIA chiefs talking Wagner with their Russian counterparts). The Ukrainians are nervous. Zelenskyy, understandably, and justifiably from his perspective, has condemned these moves. But there is now greater recognition that this war is not only a Russo-Ukrainian armed conflict but also a European Great Power war, partly a proxy war but becoming less proxy with every passing day.

The special proxiness of all this is illustrated by two contradictory trends. On one hand, we have the arming of Ukraine, on the other the refusal to supply Ukraine with all the arms it wants. The puppet-masters are pulling the procurement strings here. NATO seems still to be committed, just, to avoiding a direct clash with Russia. Some weapons are thus off the table (as Ben Wallace, the UK Foreign Secretary, recently admonished the Ukrainians in his ‘We’re not Amazon’ outburst), and Ukrainian attacks on Russian territory are very much not part of NATO’s plan. In this context, it makes some sense for initial contact to take place over Ukrainian heads.

But this is all very complicated for the Left. How might we distinguish a pacific left-wing move to end the war through negotiation from a cold-blooded Kissingerian realism in which a small state is sacrificed to Great Power interests? This is particularly difficult in a historical moment when there have been no large-scale protests against the war, and when Sir Keir Starmer’s New New Labour is in lockstep with the Tories and the British military establishment on the need to prolong the war by reinvigorating NATO. The pacifist wing of the Labour Party has been pretty much silenced; Corbyn is marginalised; and Cabinet members are prohibited from supporting the Stop the War group.

Perhaps it is best, to begin with, to think of the choices on offer as radically imperfect and unjust. A ‘just’ outcome, involving the removal of Russia from Crimea and the trial of Vladimir Putin, would be extraordinarily violent—perhaps cataclysmic. The ICC likes to talk about ‘no peace without justice’, but its vain, performative, diplomacy, rather like the discussions about Ukrainian membership of NATO, is in this case likely to be an obstacle to ending the war, and to provoke a more existential struggle to the death. Likewise, the Ukrainian endgame seems immensely unpromising: a NATO-funded war of attrition—the dreaded meat-grinder—in Luhansk and Donetsk. NATO itself seems committed to prolongation, giving the Ukrainians just enough to keep going but not enough to win. Could it be that NATO officials themselves would secretly prefer not to see the Ukrainians on the Russian border to the East and a world in which Ramzan Kadyrov is in possession of the world’s biggest nuclear arsenal?

It may be time, then, for the Left to recover its more innocent anti-war credentials. After all, there are numerous constituencies—self-promoting statespersons, the military-corporate sector, men of violence, a pugilistic media—with a deep desire to prolong war.ii Now, befuddled by the claims of justice and sovereignty, we, too, seem drawn to a war about which we should be much more sceptical.

i Indeed, should we be thinking and speaking about this war as much as we are? In Puerto Rico recently I was at a conference at which there was an underlying atmosphere of restraint as scholars from the Global South either refused European war talk in favour of a dissection of displaced or forgotten wars elsewhere, or were more interested in probing structure over crisis in their diagnoses of global disorder.

ii No wonder it has political appeal. War can have a clarifying effect on politics: the apparent muddiness of local political life gives way to the grand, simple gesture and the great on-off switch of a certain kind of friend–enemy distinction.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.