Katherine Ann Power is 74 years old and happily married to her wife of 15 years. She’s a proud grandmother. She has just gotten her hair cut, and on this early October morning the sun is beaming down on her as she walks along Seashore Boulevard near Boston’s South Station.

Power glances at the bag I’m lugging — my uncle’s green military bag from the Vietnam War, which I now use for art materials. “That bag looks heavy,” she says.

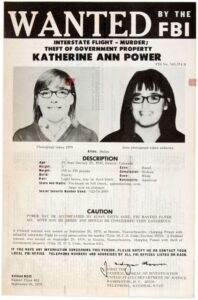

Fifty-three years ago, Power raged against that war, as many young people did. But the antiwar action she and four friends took veered toward violence and put her on the FBI’s most wanted list for longer than any other woman in U.S. history, and, eventually, in prison.

Power waited in the switch car while her fellow militants robbed the State Street Bank & Trust in Brighton. One member of her crew, William “Lefty” Gilday, lingered behind the rest and fatally shot Boston police officer Walter A. Schroeder in the back. Power says this was never the plan.

It was the second bank her radical crew had robbed, along with robbing and blowing up the state armory in Newburyport, to fuel the antiwar movement. But this robbery was their final act. After they turned on the car radio and heard about the officer being shot, Power packed up her belongings and went into hiding.

Power was a fugitive for 23 years. Assuming the name Alice Metzinger, she led a low-key new life in Corvallis, Ore. as a restaurant owner, devoted mother, and upstanding community member until her self-initiated surrender to authorities in 1993.

Her story was not neatly resolved by the prosecution that followed. In a 1994 profile in the New Yorker, Lucinda Franks wrote, “The woman who left Oregon last fall was praised, lionized, and wept over, and the woman who was then arraigned in Massachusetts was as strongly derided and condemned.”

Power was unforgivable to some and an emblem of idealism to others. She served six years in Framingham State Prison — Massachusetts’s only women’s prison — and was released on Oct. 2, 1999.

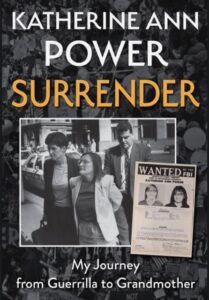

In her new book, Surrender: My Journey from Guerrilla to Grandmother, Power traces the arc of her thinking after a life spent grappling with her own involvement in violence and activism and with war and eventual peace. “I had always thought of the atmosphere of rage and violence as a force of the times, an outburst over the government’s violent repression and our powerlessness to stop the war,” she writes in a chapter titled “Idealist, Activist, Militant.”

She now views her story as a cautionary tale. “Many of us who turned to violence in those days have come to see that it was a severe error in judgment,” she writes.

What seems more relevant at this point in history is her insight that secrecy, more than devotion to action or even rage itself, was what led her to violence. “As soon as you step into secrecy there’s no one who’s going to challenge your distorted thinking,” Power says. “You lose certain normal correctives.”

Sitting on a bench overlooking Boston Harbor, Power says, “It’s really important to come back to a compassionate heart and a sense of equanimity as we regard the things we have to address in the world,” she says. “Deep change takes time.”

She thinks the love of the outlaw in American culture and the instinctive rebelliousness it denotes can be healthy at times. But, she says, “Some of it overlooks an awful lot of antisocial behavior.

“What I think is important,” Power says, “is that Surrender is the title.”

Power’s book does not romanticize her time as a guerrilla. Years in prison looking inward seem to have precluded that. She writes about the work that transpired there, “seeing my defenses, identifying the many ways I had been recklessly wrong in 1970.” And she describes how, in therapy, she discovered the source of her compulsive rebellion against all authority.

There was study: “Reading the literature on nonviolence, I recognized the error and danger in thinking of a person or force as an enemy,” she writes. And there was also what she calls “spiritual development.” The latter, she says is what has enabled her to integrate her two lives, “to see myself both as a person who had done something so destructive and as someone socially and spiritually redeemable.”

Suffolk County Superior Court Judge Robert Banks — and, as many reports have it, Boston itself — did not put redemption close at hand. Banks added a 20-year probation period to her sentence that would put Power in jail for life if she or any member of her family received any benefit or profit for telling her story. That expired in 2013, which allowed her to publish her first book, Doing Time, a volume of personal essays and poetry written in prison.

“Certainly, the judge’s intention was my story should be suppressed,” she says. Her probation officer came to her cell at Framingham State Prison and told her, “If you know what’s good for you, Ms. Power, you will go away and be quiet.”

Deep Change

The event: Surrender, a reading and discussion with Katherine Ann Power and Michelle Axelson

The time: Thursday, Oct. 12, 5 p.m.

The place: The Wilde at the Gifford House, 11 Carver St., Provincetown

The cost: Free

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.