On a low whitewashed outbuilding in the grounds of HMP Grendon, close to double rows of tall barbed-wire fences, an image of Elvis as a cowboy with the orange-mulleted head of David Bowie cuts a surreal figure. The image announces a new studio-cum-art gallery at Europe’s only fully therapeutic prison, where 260 inmates – 70% of them lifers – spend five days a week in therapy facing their crimes. “We’re the only prison in the country that has no segregation unit but has an art gallery,” says Grendon’s head of clinical services, Richard Shuker.

The Bowie/Elvis work is part of a show titled Imposter Syndrome by the artist Dean Kelland, the fruit of a nearly five-year residency organised by Ikon Gallery in Birmingham at the category B all-male prison, located in the Buckinghamshire countryside. A group of us have passed through those massive chain mesh fences, beyond security gates and a sniffer dog to visit Kelland’s show alongside a presentation of the inmates’ artworks. Despite all these precautions, there’s a celebratory mood as inmates, prison staff and guards pack in, chatting and admiring the works.

Paintings of Noel Gallagher, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, vibrant hummingbirds, rainbow flowers, prints of peace signs, sketches of moths and bees crowd the walls, salon style. A disquieting canvas portrays a shaven head with prison bars growing through the skin of the face, which twists in a grimace. “It’s about how the prison environment gets woven into you, no matter how you rail against it,” says its creator, N from D wing. The men are highly articulate about their work, hardly a surprise given the time they spend in small groups forensically dissecting their crimes, which range from armed robbery and rape to child abuse and murder.

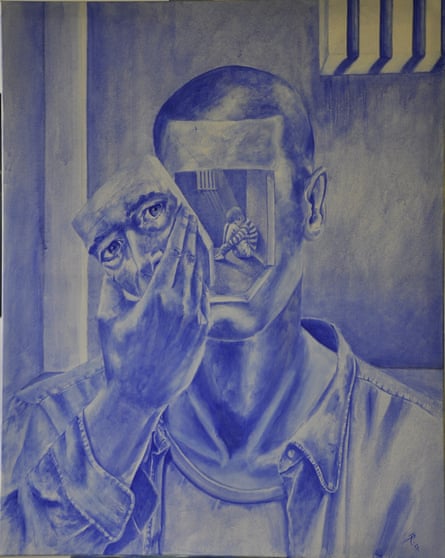

High above our heads, a large monochrome self-portrait shows an inmate removing the front panel of his face to reveal a scared child clutching his knees in an empty prison cell. Another canvas shows a shackled prisoner with a hammer inside a head made of bricks, smashing his way to freedom. “I did a series of paintings about what’s on the inside, behind the masks we’re wearing all the time,” an inmate identified as B from C wing tells me.

B has been in institutions since he was 11. But Grendon is different, the inmates say: it lacks the hierarchies and violence of ordinary jails. “Here there’s no fights, people can express themselves,” an inmate who writes poetry notes. “In other prisons you’d be seen as weak for that and open yourself up to bullying.” Grendon was founded in 1962 as a radical carceral experiment and is divided into five wings (communities) of about 40 men plus an induction unit. Inmates must apply to join the prison and spend up to six months being assessed before they can begin the intensive four-year therapy. Some can’t hack the extreme scrutiny and request to return to what they know, but statistics from criminological studies show that inmates who complete at least 18 months of therapy at Grendon are 20 to 25% less likely to reoffend than in conventional prisons.

“Prison can retraumatise people and if you don’t address it, it will be ongoing,” a female therapist (or facilitator, as they’re called at Grendon) tells me. “You have to believe people change. I’ve seen it.” Shuker agrees: “The thing that is unique here is that everybody feels they’re part of a shared goal. They want to make it work. At Grendon we say: ‘This is your prison, you’re responsible for making it safe, sort out your differences.’”

Every decision is taken democratically, by vote – including the choice of resident artist. Kelland recounts his interview with the men before he was accepted on the scheme. “One of them asked me what my work was about and I told him ‘flawed masculinity, cycles of failure’. And he said: ‘Well, you’re in the best place then. You’re not gonna find any more flaws than are here.’”

But Kelland, who describes himself as “a working-class lad from Great Barr”, has come without judgment, with a remit to support the inmates in their artistic pursuits and make work about the experience. The prints, collages and films they’ve developed collaboratively are testament to the trust he has managed to build in the prison community. Masks are a core motif in Kelland’s show, in part because of the requirement to anonymise the men who feature in it and because he is interested in the idea of social veneers, which dovetails neatly with the fact much of the psychodrama the men undergo involves masks.

Among the most powerful works in Imposter Syndrome is a multi-channel video installation, Absolute Beginners (2022), featuring portraits of the men wearing neutral masks. Shot in semi-darkness, it shows the moment each confronts their reflection in a mirror after years of not seeing themselves in some cases. Most of the men struggle to hold their own gaze through the eyeholes of the white mask, soon looking down or away. “It was really disconcerting,” N tells me. “It felt like being stripped naked. I felt a twinge of sadness that I spent my life wearing the armour and the masks.” At Ikon, where the main iteration of Impostor Syndrome is on display, the men’s images are projected on to a monolithic black cylinder and the viewer is obliged to walk around it to see them, aping the circular flow of the prison activity yard.

The level of the inmates’ engagement with Kelland’s work is evident in a dialogue wall the artist set up at Grendon, reproduced at the Ikon show. You can see how ideas materialised and proliferated there as Kelland would pin up notes and images and the men jotted down their responses. Elvis has been a major touchstone, embodying both the male ideal and its failure. Photos of the singer along with Grayson Perry, Boy George, Tupac Shakur and Bowie point to an intense exploration of male role models. David Beckham, however, didn’t make the grade and has a giant cross through his face.

after newsletter promotion

The filmed performance So the Days Float Through My Eyes (2023) marks the culmination of Kelland’s collaboration with the inmates. A ragtag group of men in screenprinted Bowie masks (including Kelland) stand in a silent row. They step forward in turn, holding up placards with lyrics from Bowie’s 1971 hit Changes that seem poignantly resonant with their incarcerated state: “I’ve never caught a glimpse how the others must see the faker” and “So I turned myself to face me”. Kelland originally planned that the men would discard the signs, but they told him that didn’t work. “It’s those little victories for me where they felt they had authorship and were able to say: ‘No, Dean, do it this way,’” the artist says. “That’s been massive.”

The prison artist residency was launched in 2011 by the Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust and Ikon came on board in 2014. Since then, the gallery has expanded the programme’s reach, installing a producer at the prison, James Latunji-Cockbill, who with Kelland spearheaded the establishment of the art studio and gallery at Grendon. It’s changed the goalposts and the ambition of the project, according to Latunji-Cockbill: “We’ve seen traditional prison arts and crafts almost fall by the wayside as our group’s artwork has become more like a fine art practice.” As well as helping the inmates with painting and drawing, Kelland has set up a press for screen printing and invited other artists in to teach them etching. Having seen the enormous benefits, Ikon hopes to roll out this workshop model in other prisons.

At a symposium held after the exhibition-viewing, several prisoners give speeches about how working with Kelland has transformed their art and their lives. “Every Wednesday, when I come to the workshop, I’m reminded I’m not just an offender – I do have a voice through art,” says M from A wing, who has won silver for the past two years in the annual Koestler prison art awards for his textile works. M’s entry this year was a pair of blue fabric therapy chairs that he had stitched with bright yellow words used in counselling sessions. “For me it was about the chairs speaking of all the people who sat in them and talked about their lives. Those chairs hold so many secrets,” he explains. Likewise, B from C wing speaks movingly of how valuable it has been to receive constructive feedback about his art. “Prison is an abrasive place – normally, people will say, ‘Fuck off you prick’ – but working with someone in the arts, it’s wholesome, it feeds the soul. This is what pulls us forward, to be part of something much bigger than us.”

As we are herded out of the prison complex under towering, triffid-like lights, rabbits scamper incongruously on the tended grass verges. It seems incontrovertible that art and therapy can play a huge role in rehabilitation. Kelland, for his part, is pleased with what he and Ikon have achieved: “What we have is prisoners who will leave having worked with us, who will see the possibility of working in creative practice and may even call themselves artists. That’ll do me.”

-

Dean Keller: Imposter Syndrome is at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, until 22 December

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.