Happy International Day of Democracy!

It’s with a heavy heart we tell you that the United States is considered a “flawed democracy” by the Thinkers at The Economist, a respected British publication for rich people.

We’re lumped with the likes of Estonia and Israel, Slovenia and South Africa, Hungary and Latvia, Malta and Malaysia. Ouch. “Flawed democracies are nations where elections are fair and free and basic civil liberties are honoured but may have issues (e.g. media freedom infringement and minor suppression of political opposition and critics),” The Economist explains. “These nations can have significant faults in other democratic aspects, including underdeveloped political culture, low levels of participation in politics, and issues in the functioning of governance.”

The good news is the U.S. did great on “electoral process and pluralism,” “political participation” and “civil liberties” — but tanked on “political culture” and “functioning of government.” Hmmm. Wonder why that is!

In the interest of furthering the cause of American Democracy on this International Democracy Day — a day the United Nations sets aside to reflect on democracy as a “universally recognized ideal” providing for the protection and realization of human rights — we’d like to share a few ideas.

Elections

How about expanding the U.S. Senate so states like South Dakota, with fewer than 1 million people, have more senators than a state like California, with 40 million people? Right now they have exactly the same number of senators, and that can’t be right!

While we’re at it, let’s rejigger the Electoral College, which had the right idea by refusing to grant the great unwashed (non-land-owning/non-White/non-male) masses the direct vote for president. The Electoral College gives small states like Wyoming one Electoral College vote for every 193,000 people or so, while California gets one Electoral College vote for every 727,000 people or so. This grants even more power to the minority in wee states, which keeps those big, unruly, coastal bully states in check. It also allows for the loser of the popular vote to become president. Whew! One person-one vote is overrated.

Also, allow corporations and their billions to “speak.” This ensures fundamental fairness in the political process. (Oh wait — we’ve already done this. It’s so hard to see its effects on the political system that it’s easy to forget!) Short election seasons, caps on political spending, prohibitions on private contributions and public financing are for losers.

Discredit independent experts and the press and convince voters that the only folks they can believe are the ones in power. Then, refuse to accept election results if your side loses.

On a somewhat more serious note, some argue that a parliamentary system is a more functional form of democracy than the one our Founding Fathers invented. It lets little parties hold seats in the legislature, something virtually unheard of in our system, and can help reduce gridlock and obstructionism by allowing the majority party in the legislature to govern at the executive level as well.

In American democracy, the legislative (Congress) and executive (president) branches are elected separately. The executive is independent of Congress. So you can have one party in the White House and the other party dominating Congress, and might get a lot of nothing as a result. Not that this happens very often.

In a parliamentary system like Great Britain’s, though, folks elect the legislature — i.e., Parliament — and then Parliament elects the Prime Minister, who serves as chief executive. There’s usually a separate figurative head of state with no real policy power, like Queen Elizabeth II or King Charles III. Of course, when Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, the king was the head of government and he managed the British Empire with Parliament in tow, which the founders found distasteful. Also, the British wore funny wigs in the halls of power, a weird practice that didn’t formally end until 2007, though they’re still worn for some ceremonies (and by die-hards and balding people). Both of these facts may have had something to do with the founders’ rejection of the parliamentary system.

Nothing’s perfect

The point here, really, is that American democracy is not perfect, but has arguably produced some of the greatest freedom, science, technological advances and innovation that the planet has yet seen.

American democracy is an aspiration. It has withstood civil war, struggles over civil rights, waves of immigration that have always been met with intolerance — but the melting pot eventually did its job. This system has produced wealth and stability and a march toward fairness, however uneven. Its benefits may not be distributed equally, but it bends toward justice. Right? Switzerland and such do a pretty sweet job of things, but — yeah, Switzerland.

The future of American democracy?

Brian Levin, professor emeritus of criminal justice at Cal State San Bernardino and its Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, is buckling up for a very bumpy ride. He expects political violence in the very near future. A rise in hate crimes. Political tribalism. Racial polarization. Rampant distortion and misinformation amplified by “high transmitters who subscribe to the very worst undemocratic methods,” employing conspiracy theories, bigotry, scapegoating. Degradation not just at the top, but at the local level (been to a school board meeting lately?), further eroding trust in our institutions.

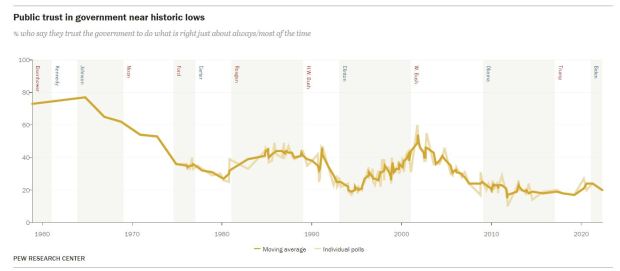

Talking to Levin was terrifying. I missed dinner. In 1964, 77% of people said they trusted the government, according to the Pew Research Center. The year Richard Nixon resigned — 1974 — it was 36%. Last year, it had plummeted to 20%.

Chalk some of this up to the rise of the Internet and the ability for loonies to broadcast their looniness loud and clear, find other loonies and plot loony mayhem. The result, Levin said: a frightening fragmentation.

Chapman University political science associate professor Fred Smoller is inclined to agree. That all this is happening as mainstream news struggles is no coincidence.

“In a democracy, citizens need to have access to information to make informed decisions. Unfortunately, we have not figured out a way for the press to pay its bills,” Smoller said. “This has resulted in a tragic collapse of local news coverage and the infusion of entertainment values in many news coverings ….

“James Madison summed up the problem well: ‘ A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or, perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: And a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.’”

Are we in a momentary blip of political insanity? Or is this the beginning of the end of the American Empire? In “The End of the American Century,” author David S. Mason argues that this has already begun.

For our part, we are stubbornly Pollyanna. We’re most relieved to find that Dan Schnur, politics/communications/leadership professor at UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies, Pepperdine University’s Graduate School of Public Policy and USC’s Annenberg School of Communications, shares this optimism.

He quoted Mark Twain: History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme. “This county has been through periods of hatred and division since before it was even a country,” Schnur said. “The specifics are different, but the overall challenge is definitely not new.”

He points to Jon Meacham’s book, “The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels,” which examines how we overcame these divisions. “It isn’t simply a circle-of-life, good-overcomes-evil, Luke beats Darth type of thing,” Schnur said. “Some are familiar stories of larger-than-life heroes — Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr. — but most of them are much more improbable individuals who stand up and push back.”

Our institutions are strong, he said. Smart people have used the U.S. Capitol after Jan. 6, 2021 as a metaphor for the nation as a whole: It was damaged, but it survived. That’s precisely the lens to look through. “There has not been a sustained period in the last 240 years where we haven’t faced these type of challenges and sustained some damage along the way. But at least so far, we’ve found a way to repair the damage.”

Past performance may not be indicative of future results, as the disclaimer goes — but it’s encouraging. Personally, Schnur has come full circle — from enthusiastic optimist, to front-line cynic, back to optimist again. He takes heart for the same reason we do: the kids.

“I’m lucky. I get to spend most of my days with some of the most impressive young people in California. I can’t help but to feel better about where we’re headed.”

Every generation seems to grow more tolerant, more worldly, more rational, more critical when it comes to messages and sourcing. Our kids will bring our nation closer to its ideal, and their kids will after them.

It’s easy to say young people will save us, but Schnur’s theory is based on tangibles. Gen Z and Millennials may vote in smaller numbers, but they volunteer their time back in their communities in larger numbers than any generation in recent American history. Unlike traditional partisan politics, volunteering doesn’t demand absolute ideological adherence. “If you volunteer at a community cleanup next to someone who disagrees with you on immigration or abortion, you leave understanding they’re not stupid or evil, they’re just a good person who doesn’t happen to agree with you on everything,” Schnur said.

If a crazy 2024 with pockets of violence is, indeed, inevitable, we cling to the belief that, eventually, things will settle down. If you don’t agree, you’ve obviously sprung from the loins of the devil, don’t like chocolate and enjoy torturing kittens. Happy Day of Democracy!

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.