Lessons From the Historic Crime Drop

Understanding mass incarceration’s limited contribution to the historic crime drop, which began in the 1990s, strengthens the case for pursuing substantial decarceration. Rates of crime reported to the police in the United States grew dramatically beginning in the 1960s, reached their peak in the early 1990s, and then plummeted over the subsequent two and a half decades. The reported violent crime rate, for example, peaked at 758 per 100,000 residents in 1991 and fell to a low of 362 per 100,000 in 2014 – a 52% drop. In 2022, the most recent year for which national data are available, the reported violent crime rate was 381 per 100,000 – still 50% lower than its peak rate in 1991. Several studies have established that the increased confinement of people in prisons, from about nearly 200,000 in 1972 to a peak of nearly 1.6 million in 2009, accounted only modestly for this crime drop.

Over two dozen countries experienced crime waves and drops comparable to that of the United States but most did not expand imprisonment anywhere close to the scale of the United States. In contrast, incarceration levels in the United States exploded, quadrupling the prison population between 1972 and 1991, the period of the crime wave. Imprisonment levels then doubled again between 1991 and 2009, while crime rates were falling. The prison population finally began its modest decline in 2010, entering a nearly decade-long period when both crime and incarceration levels declined in unison.

Scholars examining state imprisonment trends during the period of extreme growth conclude that incarceration contributed only modestly to the crime drop. They find that in the 1990s mass incarceration accounted for as much as 35% or as little as 6% of the crime drop. These estimates depend on the type of crime under investigation as well as the methodology and assumptions used by analysts. Since the turn of the century, mass incarceration appears to have made almost no contribution to the crime drop. Reviewing the four-decade period when incarceration levels increased without any consistent relationship with crime rates, the National Research Council has concluded that “the increase in incarceration may have caused a decrease in crime, but the magnitude of the reduction is highly uncertain and the results of most studies suggest it was unlikely to have been large.”

Some of the reasons that mass incarceration has contributed so little to community safety are:

- The War on Drugs has failed to mitigate the harms of drug use by incarcerating drug sellers who are easily replaced, and by failing to treat substance use disorders, while diverting resources from more effective interventions;

- Incarceration often fails to offer adequate rehabilitative services that can address factors such as economic disadvantage and/or trauma that contribute to crime, and sometimes exacerbates these problems through the experience of incarceration and its associated collateral consequences; and

- Increasing sentence lengths does not deter crime, and thus does not promote community safety as shown by an abundance of criminological research.

Why Longer Sentences Don’t Work

A key part of mass incarceration has been the rise of lengthy sentences. More Americans are serving life sentences today than the total prison population in 1970. In addition, 19% of the prison population has already served at least 10 years. Yet, research has shown that lengthy prison terms often incarcerate people long after they have aged out of crime:

- Recidivism rates drop dramatically among people who have served longer than six to 10 years compared to those who have served shorter sentences.

- “Criminal careers” typically end within approximately 10 years.

- Research on the age-crime curve, which measures the proportion of individuals in various age groups who engage in crime based on arrest trends, shows that for a range of offenses, including robbery and murder, criminal offending peaks around the late teenage years or early 20s, then begins a gradual decline in the early 20s.

Longer sentences also fail to deter others from criminal activity. As Daniel Nagin, professor of public policy and statistics at Carnegie Mellon University and a leading national expert on deterrence, writes: “Increases in already long prison sentences, say from 20 years to life, do not have material deterrent effects on crime.” Long sentences are limited in deterring future crimes because most people do not expect to be apprehended for a crime, are not familiar with relevant legal penalties, or commit crime with their judgment compromised by substance use or mental health problems.

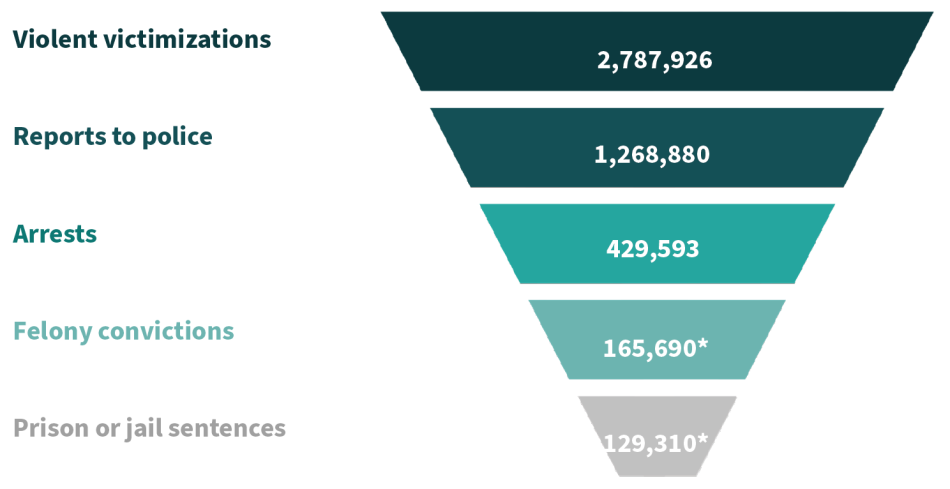

Another way to understand mass incarceration’s limited contribution to the crime drop is by visualizing the system itself as a funnel. We illustrate the funnel model using the violent crimes of aggravated assault, robbery, rape, and murder/nonnegligent homicide. According to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), a nationally representative snapshot of victimization experiences across the United States, in 2022 the number of violent victimizations surpassed 2.7 million yet fewer than half were reported to police. While reporting rates vary by crime type, individuals choose not to report for a variety of reasons including handling it informally, thinking it was not serious enough to report, or not believing that law enforcement could or would do anything. Of violent offenses reported, roughly one-third resulted in an arrest. For a variety of factors, as cases exit or proceed through the criminal legal system, a fraction of those arrested – roughly 130,000 people – are sentenced to a term of incarceration. In other words, the criminal legal system addresses a small proportion of crimes that impact the safety of our communities.

Figure 5. The Criminal Legal Funnel and Violent Crime

Note: Violent crime types depicted include aggravated assault, robbery, rape, and murder/nonnegligent homicide. Because the NCVS does not measure homicide victimizations, the UCR murder/nonnegligent manslaughter count is added to the violent victimizations count. Violent victimizations, reports to police, and arrests use 2022 data, the most recent year available.

* Felony convictions and related incarceration for the above-listed crimes use 2006 data, the most recent year available, and pertain to state courts. In 2006, there were 2,355,704 violent victimizations, 1,417,745 violent crimes reported to police, and 611,523 arrests.

Sources: FBI crime data explorer. Crime in the United States annual report, 2022: CIUS estimates “Crime in the United States (CIUS), Table 1” & persons arrested “Estimated number of arrests, Table 29.” FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program; Rosenmerkel, S., Durose, M., & Farole Jr., D. (2010). Felony sentences in state courts, 2006 – Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Thompson, A., & Tapp, S. N. (2023). Criminal victimization, 2022. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Researchers have identified many factors, other than incarceration, that contributed incrementally to the U.S. crime drop. These include the decline of the crack cocaine market, a decline in the share of the population that falls into high-risk age groups, and the growing immigrant population who have lower crime rates than native-born Americans – and there is ongoing debate about the magnitude of impact from factors such as improvements in the economy and changes in policing.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.