On Friday afternoon in Block C, which houses the Orleans Justice Center’s juvenile pod, nine shackled youths studied on laptops in the jail’s school. The remaining seven incarcerated male juveniles were locked in their cells.

One teen lay in bed, his small frame almost undetectable under a beige blanket. Taped on his wall were a September calendar with each proceeding day crossed out and a progress report showing three As and a C in world history.

Cell blocks can house 60 inmates. But under a new law backed by Gov. Jeff Landry, the 16 youths in Block 2C are considered adults in court but must be separated from the 18-and-older population in jail.

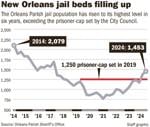

Sheriff Susan Hutson called their presence an added strain on a jail that is already over capacity, with the population ticking upward to its highest level in six years as police have stepped up arrests and judges have set higher bonds for them, city data show.

At 1,460 individuals as of Friday, the jail’s population has blown past a City Council-imposed limit of 1,250, set in 2019. That cap came as a compromise after a long political fight over the size of the jail that straddled mayoral administrations and reflected a broader effort toward prison reform that addressed mental health needs of inmates. The jail’s target population, as stated in that ordinance, was 998 inmates—a number that would let the city make good on its pledge to the MacArthur Foundation, from whom the city accepted a $2 million grant.

In May 2021, when low-level offenders were released during the pandemic, the city hit a low of around 750 inmates.

Repercussions for failing to cleave to the City Council’s cap are unclear. Even less clear is which party should bear them.

“I do not decide who comes into this jail, and I do not decide when they leave,” Hutson said last week in an interview in the jail’s fourth-floor conference room. From that vantage, she can see inmates as they are discharged, sometimes padding across the parking lot in jail-issued orange slippers because they lack shoes, she said. “I can’t stand at the door and say, ‘Don’t let them in.'”

While stakeholders describe a system-wide crisis in the rising jail rolls, Attorney General Liz Murrill, whose office is prosecuting Orleans Parish arrests made by state troopers in the city, offered a solution that’s simple but not easy.

“I think people should stop committing crimes in New Orleans and that would alleviate the crisis,” Murrill said in a statement.

‘Good with the bad’

Over the last year and a half, New Orleans has seen a stark, welcome drop in violent crime, from the country’s most murderous city to one where declines in crime are among the steepest.

Law enforcement officers credit effective federal, state and local partnerships, including the Louisiana State Police’s new Troop Nola and FBI intelligence-led operations, for targeting the most dangerous repeat offenders and taking them off the streets. The reductions in violent crime began in mid-2023, well before Troop Nola launched patrols in the city, and have continued this year.

Meanwhile, bonds have ticked up along with arrests, with an average felony bond sitting at $14,359, compared to $10,468 at this time last year, according to the City Council’s Bond Paid Per Charge Dashboard.

“We have to take the good with the bad. … (The jail) is overcrowded because we have a proactive law enforcement response right now with the Louisiana State Police. We have proactive prosecution with the Attorney General,” said Matt Dennis, founder and director of enforcement for ASAP Release. “We have to start to look at how we handle this limited jail space.”

Citing an 83% re-arrest rate for people leaving the Orleans Justice Center, Hutson said the city’s magistrate judge and commissioners are setting higher bonds because they’ve become well acquainted with offenders they’ve seen in their courtroom seven or eight times. The average stay at Orleans Justice Center is now 53 days, Hutson said, compared to a national average of 43 days.

“We’re taking in more people than we are releasing, and that’s a big problem. It keeps going up,” Hutson said.

Loyola University law professor William Snowden sees politics as a factor.

“When a person is accused of committing a crime when they are out on bond, the judge gets blamed. And I think judges are concerned about how their decisions are painting them in terms of whether they’re keeping New Orleans safe,” Snowden said.

Hutson’s office said it’s taking steps to deal with the bloated jail rolls, including winnowing its population of prisoners assigned to the state Department of Corrections from around 100 to 32 as of Thursday. She’s discussed with District Attorney Jason Williams moving misdemeanor cases to New Orleans Municipal and Traffic court and expediting screening decisions. Williams’ office did not return requests for comment.

Hutson also has brought on a new deputy corrections chief, Jeworski “Jay” Mallett, a veteran of the Mississippi Department of Corrections. Mallett has made overtime mandatory for the OPSO’s 190 personnel. They went from 14 to 16 shifts per month, with each shift at 12 hours long.

“A lot of people were working overtime anyway. Now it is built into the schedule,” said Col. Debra Hammons.

Hutson said she would consider her office fully staffed with 463 workers. But the low pay, long hours and challenging conditions make “a tough sell” of the job.

“The city’s summer interns make $16 an hour. These are high school students. Lifeguards make $17, and our deputies make $18,” she said. “I’m asking them to take care of people who have burned their children up in a house or dismembered somebody.”

‘Too full’

The swelling population and staffing shortage threaten to undermine the jail’s progress toward compliance under a 12-year consent decree overseen by a federal judge. Federal monitors in May said inmates in unmanned pods crafted weapons from brooms, buckets and metal sheeting, fueling a surge in inmate-on-inmate assaults. Hutson released in May a corrective action plan to address 11 areas in which monitors identified backsliding.

Violence in the city’s lockup hit a boiling point a year ago, when deputies staged a brief walkout after inmates started multiple fires.

At that point, the jail’s population stood around 1,200. Now, the jail is so full that 32 people jailed recently had to sleep on the floor in side rooms near the low-security open dorms, in cot-like beds called “boats,” Hammons said.

The plumbing, air conditioning, and even the carts used to transport meals are stressed, jail officials said, not to mention deputies “run ragged,” Hutson said. When the long-debated “Phase III” of the jail opens with a planned 89 beds for mental health patients, capacity will be even more limited, she said, with another facility in the complex, the temporary detaining center, to be shuttered.

“We can’t have this many residents per deputy,” Hutson said. “That will keep us from being able to comply. It’s just not going to be possible. And we will have to go into federal court and say, ‘We are too full’ at some point.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.