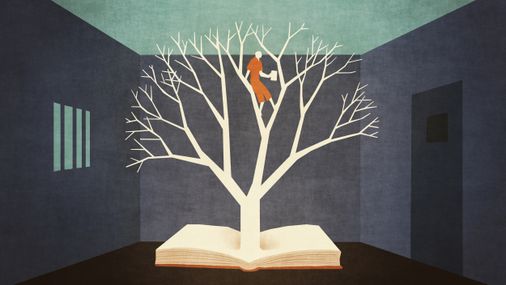

Many Americans today believe that their rights to free speech are being trampled. However, what is the possibility that the government will incarcerate you simply because of your criticism? Perhaps not very high. However, if you’re already currently incarcerated like me, the chances that government officials will retaliate against you for dissent, or restrict your access to books, is exponentially higher.

Book bans in prisons are done under a shroud of legitimacy. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1989 ruling in Thornburgh v. Abbott allows prison officials to reject incoming mail if the writing is “determined detrimental to the security, good order, or discipline of the institution,” or if it might facilitate criminal activity. While it makes sense to grant staff the power to prevent prisoners from obtaining books that encourage violence or help them escape, such power is often abused–particularly when the courts grant “broad discretion” to officials.

This lack of accountability has had huge ramifications, at least for prisoners in Michigan. Some prisons reject books so often, and with such disregard for First Amendment rights, that most prisoners don’t even attempt to purchase books. Just look at the Michigan Department of Corrections’ (MDOC) restricted book list and you will begin to understand what I’m talking about.

As of April 2022, the list includes more than 1,200 publications, including 1,000 books. Some of these are computer programming manuals, tax guides, or books about carpentry, cars, truck driving, and welding. When the list of censored materials went public last year, it generated a lot of headlines, but no real action.

The funny thing is all of these topics are actually taught in prison classes facilitated by the MDOC itself. Trying to rationalize such decisions requires mental gymnastics, but they try. One employee told me that allowing us to read books in MDOC-facilitated classes makes sure we’re reading “under [MDOC] ‘guidance,’ ensuring that [prisoners] do not do anything inappropriate with the material.” (Note: they also let the prisoners take the books back to their rooms).

As a currently incarcerated prisoner, I have filed several grievances about the arbitrary nature of the MDOC’s censorship activities. However, the grievances were rejected based on vague, irrational justifications. This includes the fact that a prisoner apparently “can’t grieve the content of a policy” – even when no such policy exists.

‘They fear a prisoner’s ability to influence others – even in positive ways.’

In January 2023, PEN America sent me its 2022 Prison Writing Awards Anthology, but my facility refused to give it to me, because I authored one of the book’s articles. Their reason was that giving me the book would grant me the power to “exert pressure to have the story distributed by or to other prisoners as a means of communication with or influence of other prisoners confined in MDOC facilities and impact the atmosphere and threaten the order of the facility.” This justification has nothing to do the article’s content, and essentially denies all prisoners the ability to obtain a copy of writings that they produce while incarcerated. Several people have filed multiple grievances regarding this issue, and at multiple facilities, but MDOC has upheld the decisions at all steps of the process.

And the haphazard censorship doesn’t stop with material that can teach prisoners practical skills, either. I know an inmate who said he had a James Patterson book rejected because the plot includes a detective being killed. While I do not encourage anyone to engage in violence, censoring the mere mention of such incidents would require prisons to ban TVs, radios, and most fiction books.

Michigan prisons also try to censor dissent. The MDOC has concluded that prisoners cannot receive any books or articles that have been authored by other prisoners because allowing prisoners to impact the facility’s atmosphere “threatens the good order of our facilities.” In other words, they fear a prisoner’s ability to influence others – even in positive ways.

Such reasoning clearly violates U.S. Supreme Court precedent, which requires officials to make an individualized assessment that the mail is actually a threat. Blanket bans are not allowed under Thornburgh v. Abbott. However, the only way to challenge such decisions involves filing a grievance, and, if that fails, a federal civil rights lawsuit for a constitutional violation by the government. For 99% of prisoners, this process is almost impossible to do on their own because of the complexity of the law, as well as the courts’ reluctance to question the rationale behind prison staff decisions. Most cases are thrown out during summary judgment based on procedural reasons, even when prisoners have strong cases.

Even when a prisoner’s issues are strong, they are unlikely to find an attorney. According to the 1996 crime bill, the Prison Litigation Reform Act, attorneys representing prisoners can only receive 150% of what a prisoner wins in a lawsuit. Since most prisoners filing federal lawsuits only win $1 for “nominal damages,” attorneys representing these people are only entitled to $1.50 in legal fees, meaning most attorneys decline taking such cases, preventing prisoners from holding authorities accountable for violating their constitutional rights. In this sense, prisoners are among the most vulnerable populations in America. The government controls every aspect of our lives, and even when it arbitrarily violates our rights, we have little to no recourse to vindicate our rights.

Given this, it should not surprise us that the censorship is only increasing in prison. Once the courts refuse to hold government officials accountable, the only other avenue prisoners have is the press. But, when that is denied, then what? So, is there any doubt that censorship exists in America?

Daniel Pirkel was born and raised in NW Indiana. He spent his childhood playing football, riding motorcycles and gaming. Since being incarcerated 15 years ago, he has won a favorable legal decision on appeal and earned a bachelor’s degree through Calvin University (2021) in Faith & Community Leadership in Social Work. Daniel won the Honorable Mention in 2022 PEN America Prison Writing Contest for his essay, “The Unintended Consequences of Retributive Justice” and Honorable Mention in PEN’s 2019 America Prison Writing Contest for his essay, “Parole Reform.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.