James Mannion knew what he needed.

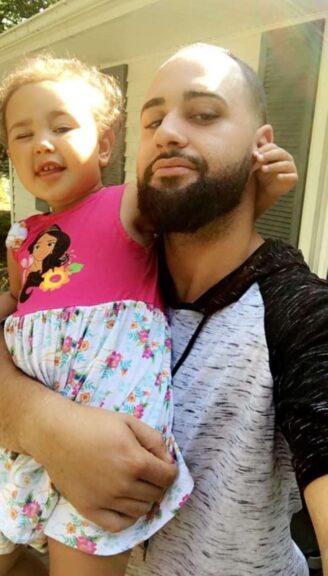

For nine months, while incarcerated in a county jail in Portland, Maine, he pleaded for a medication called buprenorphine. Mannion, a barber, recreational fisherman, and father of two, was once a regular heroin user, but had used the medication to eliminate the cravings and withdrawal he experienced whenever he tried to quit opioids cold turkey. Buprenorphine had worked before for Mannion, just as it has worked for millions of others, helping him to avoid using far more dangerous illegal drugs like heroin and fentanyl.

On Aug. 11, 2022, a doctor working at the jail examined Mannion and concurred with his self-diagnosis: He had opioid use disorder, and had once benefited from Suboxone, a common buprenorphine brand. Mannion had repeatedly written to jail officials reporting “daily cravings” for heroin and a fear that denying him buprenorphine would end in disaster. “I want help,” he wrote at one point. Later, he added: “If my cravings don’t go away, my mental state is going to get worse and worse.”

His pleas went nowhere. Three days later, Mannion was found dead after overdosing on opioids he had obtained from another inmate. “His cold body was discovered in his cell with no pulse, a clenched jaw, and blood in the mouth,” a representative of Mannion’s estate alleged in a federal lawsuit.

“When people go to jail, sometimes your first thought is: They’re safe, they’re not going to get in trouble or die,” said Taylor Webster, Mannion’s longtime partner and the mother of his two daughters. “It’s really shocking, when all your rights are taken from you and put into the jail’s hands. … He really needed medication, and this could have been prevented.”

Mannion’s death is just one example of a lingering crisis within the U.S. criminal justice system. Across the country, many leading law enforcement officials remain hostile to buprenorphine and methadone, another highly effective addiction medication, denying a uniquely vulnerable population access to high-quality care amid the worst drug epidemic in the country’s history.

A STAT investigation has found that opposition to medications for opioid use disorder is pervasive in local jails, state and federal prisons, specialized drug courts, local police precincts, and the halls of the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Despite significant improvements in medication access since the onset of the opioid crisis, much of the nation’s criminal justice system often operates with indifference to their lifesaving potential, treating them as if they were no different than illegal opioids. Many facilities offer the medications only in special circumstances, like pregnancy. Thousands more do not offer them at all.

The criminal justice system is, in theory, responsible for providing medical care to hundreds of thousands of Americans with addiction. At any given moment, the U.S. incarcerates roughly 2 million people — by far the most of any country — a majority of whom are estimated to meet the criteria for a substance use disorder. Providing medication for opioid addiction is highly effective: Those receiving methadone or buprenorphine while incarcerated are 75% less likely to eventually die of an overdose, according to one study.

The Department of Justice has failed to comply with its own guidance on facilitating access to addiction medications. The Bureau of Prisons, which is overseen by the DOJ and incarcerates over 150,000 Americans, uses clinical practices out of step with other arms of the federal government and fails to guarantee access to addiction medications for all its inmates, despite the Justice Department’s own view that failing to provide access violates the Americans with Disabilities Act.

But much of the justice system keeps methadone and buprenorphine out of reach. At least partially as a result, people being released from jail or prison are, according to one estimate, 129 times more likely than the general population to experience a fatal overdose.

The explanation from prison wardens, sheriffs, drug court judges, and other law enforcement or carceral system officials is often one of safety. Methadone and buprenorphine are both opioids themselves, and methadone in particular can cause overdose if misused. But the medications are both vastly safer than the toxic, fentanyl-dominated drug supply from which they offer an escape.

“The interviews and research we’ve done with police officers shows they have attitudes that are broadly similar to the average American’s attitude,” said Brandon del Pozo, a Brown University researcher and former law enforcement official. “There’s a lot of belief that methadone and buprenorphine substitute one drug for another, one addiction for another.”

In 2021, for example, the New York Sheriffs’ Association lobbied against a law that would have required local jails to provide methadone and buprenorphine to inmates. This year, a county sheriff in Tennessee led a failed attempt to block a new methadone clinic from opening, calling the facility a “safety and hazard concern for the citizens of Putnam County.”

Del Pozo and other experts say law enforcement officials’ attitudes perpetuate a climate in which the American public views addiction medications with suspicion; doctors are afraid to prescribe them; and pharmacies are reluctant to stock them.

In recent years, the criminal justice system has come under fire for its anti-medication approach. Increasingly, legal scholars and federal prosecutors have used the Americans with Disabilities Act and Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment, in lawsuits meant to force local governments, correctional systems, and even private health providers to prescribe addiction medications.

But change comes slowly. According to the Jail and Prison Opioid Project, a research initiative devoted to medication access in carceral settings, more than half of state prisons and an estimated two-thirds of local jails don’t offer medication for opioid addiction in any form.

“These medications are proven to reduce illegal drug use,” said David Howard Sinkman, a former federal prosecutor and attorney representing Mannion’s estate. “They’re proven to reduce overdose deaths, and they’re proven to reduce criminal recidivism rates. Unfortunately, jails, prisons, and private medical providers have erected discriminatory barriers to these treatments, and these barriers cost people’s lives.”

‘If they had treatment, they wouldn’t be there’

The 2 million people incarcerated in the U.S. constitute one-fifth of all those behind bars worldwide, despite the U.S. having roughly 4% of the world’s population. The American carceral system is built to scale: It includes 122 federal prisons, over 1,500 state prisons, and over 3,000 local jails.

While estimates vary about the share of incarcerated people with substance use disorders, and opioid addiction specifically, it is universally agreed that addiction rates within U.S. jails and prisons are vastly disproportionate.

And in a tragic cycle, thousands are incarcerated precisely because there is so little access to high-quality addiction medication to begin with. Untreated addiction often leads to further drug use, crime, arrest, and prison time. Once imprisoned, people with addiction still lack access to methadone and buprenorphine, placing them at immense risk of overdose death and furthering the addiction-incarceration cycle.

“They shouldn’t be in prison in the first place,” said Josiah Rich, a doctor and Brown University professor who co-leads the Jail and Prison Opioid Project. “If they had treatment, they wouldn’t be there.”

Much of the stigma preventing medication access in jails and prisons stems from the chemistry of addiction medications. Methadone is known as a full-agonist opioid, meaning it binds with the brain’s opioid receptors in the same way as more powerful drugs, like heroin or fentanyl. Buprenorphine is a partial agonist, meaning it occupies the receptor partially.

As a result, the criminal justice system has long sought alternative approaches that exclude opioids altogether, even though the medications are highly regulated. Some private companies that some prison systems contract to provide health services for inmates also do not provide medication: Mannion, the Maine inmate who died after being denied buprenorphine, was treated by a private system under contract with the state’s department of corrections.

Police at the national and local level also have historically resisted methadone and buprenorphine. In the past decade, the DEA and local police agencies have cracked down on doctors who prescribe and pharmacies that distribute large quantities of buprenorphine. Due in part to decades-old DEA regulations, methadone remains available as an addiction treatment only at specialized clinics, whose policies are often so restrictive that patients have dubbed the medication “liquid handcuffs.”

Even the Department of Justice, which oversees roughly 150,000 inmates in its prison network, fails to comply with its own guidance regarding medications for opioid use disorder. As of early 2024, a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services administration database showed fewer than half of federal prisons were listed as methadone providers.

The department’s standard of care is also inconsistent with accepted practice in the addiction medicine community and guidelines enacted earlier this year by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: It requires a year-old diagnosis of opioid use disorder before inmates can receive methadone, and states that methadone treatment can be discontinued as punishment for bad behavior.

Many prisons also facilitate meetings of 12-step programs like Alcoholics Anonymous, which rely on total abstinence from all substances. Narcotics Anonymous, the 12-step offshoot focused on opioids, considers methadone and buprenorphine to be “mind-altering” and historically opposed the medications’ use. Yet NA announced at its World Conference in September that the Federal Bureau of Prisons recently asked the group to make a presentation to all 122 of its wardens nationwide.

Experts say that judges, police, and prison wardens who deny access to the medications for fear that they are dangerous are actually making the opposite mistake. Failure to access methadone or buprenorphine, statistics show, is far more risky than negligible overdose risk associated with buprenorphine and low risk associated with methadone.

“Their job is to think about safety, so I don’t fault them for thinking about safety,” Rich said. “But the evidence suggests it’s much safer to have people on treatment.”

The ‘Vivitrol courts’

One Massachusetts-based pharmaceutical manufacturer, in particular, has sought to take advantage of prisons’ resistance toward methadone and buprenorphine. Alkermes, the company, makes a third form of addiction medication: a long-acting, injectable form of naltrexone, which blocks opioids’ effects.

Because naltrexone is not an opioid, it has been cast as a “non-addictive” alternative to methadone and buprenorphine.

President Donald Trump’s first administration even wrote in special favoritism to Vivitrol in its national opioid crisis response plan, specifying that the injection — which can carry a list price of over $2,000 — be used instead of methadone or buprenorphine.

But the medication has a mixed track record. While some studies initially showed it to be highly effective at preventing overdose and death, subsequent research suggested that it was associated with frequent overdoses. Those who take it experience a sudden drop in opioid tolerance, addiction doctors say, meaning that if they return to using heroin or fentanyl, their overdose risk may be higher than it was before they began treatment.

“Extended-release naltrexone is an alternative medication treatment for people with opioid use disorder, but in a head-to-head comparison with buprenorphine, it was less effective than buprenorphine because many people had a hard time starting it,” said Sarah Wakeman, the medical director for substance use disorder at Mass General Brigham in Boston. “It has also not been shown to reduce the risk of death, and in fact there are some studies which suggest there might be an increased risk of death from overdose, likely because people have a harder time starting and staying on it.”

Many judges in specialized drug court systems across the country, designed to help drug users avoid incarceration for possession charges, mandated that participants use not just naltrexone, but naltrexone in its extended-release, injectable form — in other words, Vivitrol.

Some courts became so known for this practice that they were dubbed “Vivitrol courts.” The Fairborn Municipal Vivitrol Drug Court in Ohio adopted the label as an official title.

Other courts turned to Vivitrol not out of ideology but, in local officials’ telling, out of necessity.

“I don’t believe any of the medication-assisted treatment is the cure-all,” Fred Moses, a judge in Hocking County, Ohio, said in a 2017 interview with the Cleveland Plain-Dealer. “They’re a tool in the tool belt to help people get better. They’re all legitimate treatments: methadone, Suboxone, Vivitrol. They all work in a different manner. The big problem in my county is there’s not a doctor even prescribing Suboxone, so the idea of using Vivitrol is a good thing for us. We can control it.”

Booked for medication possession

A policing crackdown is emblematic of a uniquely American tragedy. Law enforcement largely missed the signs of the emerging prescription opioid epidemic decades ago, allowing “pill mills” to proliferate and millions of dubious painkiller orders to be distributed.

Now, with the ensuing opioid crisis in full effect, the nation’s criminal justice infrastructure has finally jumped into action — but, in many cases, to deny access to the medications used to treat the addictions caused by their inaction decades ago.

The problem is that methadone or buprenorphine can be so hard to get that many drug users obtain the medications illegally. In a legal bind, many police officers treat such “diverted” medications the same as illegal opioids.

“Diversion is only a thing because of how hard it is to get treatment,” said Aaron Ferguson, a harm-reduction proponent who advocates for wider access to methadone and has used the medication to avoid the use of more harmful substances. “It prevents people from using out of desperation. Being in withdrawal makes a person incredibly compromised and desperate.”

Ferguson credits diverted methadone with saving his life and helping him avoid debilitating withdrawal on numerous occasions, including during an overseas deployment with the U.S. Navy. In his view, law enforcement officials were anything but lenient with addiction medications.

“In my experience, they were all treated the same,” he said. “It was an illegal drug. It was never considered part of any treatment.”

Still, the law enforcement climate has cast a pall over doctors and pharmacies attempting to provide vulnerable patients with a lifesaving medication. And generally speaking, the DEA has made access harder rather than easier for patients.

For the past two years, the agency has pushed for the return of certain restrictions on providing buprenorphine via telehealth. It also has threatened to investigate numerous methadone clinics and individual addiction doctors based on limited evidence, contributing to what many providers describe as a climate driven by fear.

Recently, however, a pair of Democratic lawmakers introduced a bill that would require the DEA to exclude buprenorphine from its Suspicious Order Reporting System, arguing the rules “have led to an uncertainty among pharmacies and distributors to stock and dispense buprenorphine.”

From experience, new strategies

As the U.S. grows more accepting of medications for opioid use disorder, some corners of the criminal justice system are, too. Arguably, the network of jails, prisons, and drug courts are changing more quickly than methadone clinics or the 12-step recovery world.

Many states, like Rhode Island, have aggressively sought to incorporate methadone and buprenorphine treatment into their jails and prisons. Others have been compelled to do so by a slew of lawsuits from nonprofits including the Legal Action Center and American Civil Liberties Union.

And among police, attitudes may be shifting, said del Pozo, the Brown researcher and former police chief in Burlington, Vt., where he moved to decriminalize illegally obtained buprenorphine.

Recent research shows that more experienced officers, who’ve spent decades on the front lines of the opioid crisis, are more open to taking a lenient approach to addiction medications and consider novel approaches to reduce overdose and death, del Pozo said.

“We’ve had police say that if someone has non-prescribed buprenorphine on them, they’ll just let them go, they don’t charge it as a misdemeanor,” he said. “The police we talk to in Rhode Island, for example, where buprenorphine was decriminalized — most couldn’t care less.”

The U.S. Department of Justice, itself, has pushed for reform, issuing guidance in 2022 and a reminder in 2024 that jails or prisons failing to provide methadone or buprenorphine constitutes a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Federal prosecutors have also secured recent settlements against jails, prisons, and court systems in Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, requiring each to provide full access to all available addiction medications.

But still, courts sentence people specifically to Narcotics Anonymous, mandate Vivitrol, and prohibit the use of opioid agonist therapies like methadone and buprenorphine. Thousands of jails and prisons continue to prohibit their use.

Sinkman, the attorney who represented James Mannion’s estate, said change is unlikely to come quickly — and in the meantime, restrictive policies across the law enforcement community are likely to cause more families to suffer from similar tragedies.

“Unfortunately, I think this is going to take some time,” said Sinkman. “These negative stereotypes and stigmas and cost concerns are deeply ingrained in jails and prisons and private medical providers. But we anticipate lots of lawsuits. And we will win.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.