Matt Woodhead has always wanted to expand the possibilities of theatre. Now he may well have invented an entirely new genre: the verbatim investigative dance piece. Even Woodhead is not sure how to describe his latest show, but one thing’s for sure: it’s a compelling piece of journalism and a wonderfully ambitious meshing of art forms.

Woodhill is an exposé of multiple self-inflicted deaths at the prison of that name in Milton Keynes – and the institutional failings that have allowed them to happen. In June 2018, the HM Inspectorate of Prisons reported that, “staggeringly”, a total of 20 men had taken their lives in seven years at Woodhill, higher than at any other jail in England and Wales. There have been further cases since then.

Woodhead, aged 30, is a warm, funny man committed to making theatre about challenging community-based issues. He interviewed 70 people for this project, from grieving family members to prison staff, architects, academics, lords, ministers, campaigners, former inspectors of prisons and ombudsmen – many of whose words are quoted on stage.

The play tells the story of three men: Kevin Scarlett, 30, who was found dead in his cell in May 2013; Stephen Farrar, 25, who was found dead in his cell seven months later; and Chris Carpenter, 34, who was found unresponsive in his cell after a drug overdose in 2018. The inquests into all three deaths were highly critical of the prison. Woodhead, co-director of the verbatim theatre company Lung, has spent four years working on this, partly because the interviewing process was lengthy, and partly because it took time to win the trust of bereaved families.

Today, via Zoom, I am speaking to Sophia, the sister of Stephen Farrar, as well as Carole and Linda, sister and mother of Chris Carpenter. Stephen was sporty, a good dad, and hoped to become a fitness trainer. Then he got into drugs. “With drugs come debt,” Sophia says. His troubles spiralled, and he was in and out of prison. At the time of his death, he was on remand at Woodhill, charged with theft.

“I was his little sister,” says Sophia, “and he wanted to be there for me, and not be the vulnerable one.” But she knew he was troubled. In a beautiful short film Woodhead has made to accompany the play, Stephen’s mother Janet says: “The officer who assessed Stephen on arrival at Woodhill told the jury, ‘When I interviewed him, he maintained eye contact, so I didn’t identify any immediate health concerns.’ I could have screamed. Stephen had a history of self-harm.”

While on remand, Stephen filled in a form about his mental health. “When I came into the prison, I told the reception nurse that I suffered from depression,” he wrote. “Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve been feeling very low and have cut my arms again … I’ve had thoughts of suicide. I’m up all night and can’t sleep due to constant thoughts running in my head. Please help.” He was put on a waiting list for mental health support.

“The prison had records that Stephen had tried to kill himself in 2007,” adds Janet, “and again in 2010. Why did nobody do anything? The morning before it happened, the woman who ran his computer course said Stephen was like a different man – he was really unhappy. But nobody did anything. In the canteen, Stephen said to a mate, ‘I’m going to get out of this jail, just watch me.’ But nobody did anything. That night Stephen told an officer, ‘I’m going to set fire to my cell.’ But nobody did anything.”

At Stephen’s inquest, the coroner Thomas Osborne said he was concerned that no formal risk assessment had been made of Stephen. “Almost any risk assessment tool would have identified him as high risk,” he said. “In my opinion, there is a risk that future deaths will occur unless action is taken.” And so it proved.

In August 2018, only two months after the chief inspector of prisons expressed concern about the number of prisoners who had died by self-inflicted means at Woodhill, Chris Carpenter was found dead in his cell. Like Stephen, he had been diagnosed with severe mental health problems. One day in 2015, he called Prospect Park hospital in Reading and said he was in danger of harming himself or somebody else. They collected Chris and briefly sectioned him. A few weeks later, the same thing happened again.

“He said he was going to kill someone or kill himself,” his sister Carole says. “He did it thinking he’d be picked up by them again, but they put the phone down on him and rang the police.” The police arrived to find him in his corridor outside his flat with a knife. He was charged with threats to kill and possession of a bladed weapon, found guilty and sentenced to 40 months in prison. Was he threatening anybody with the knife? “No,” says Carole. “He never threatened or approached anyone with it.”

Chris was released on parole in June 2018, but was recalled to prison one month later for breaching his licence. His father had just died and he had taken it badly. Concerns were raised with the prison that Chris might self-harm or take his own life if his mental health deteriorated. In prison, Chris started to take drugs. The jury heard that the availability of drugs brought with it a culture of debts, threats and violence.

Chris made numerous attempts to alert prison staff to the threats he was facing. On 15 August 2018, he reported that he had been threatened with a bladed weapon, and named the prisoner who threatened him. The next day he handed prison staff a note stating that he feared for his life, requesting to move to the vulnerable prisoners unit. No meaningful action was taken. Two days later, he was found unresponsive in his cell.

“He rang my mum the day before he died,” says Carole, “to say he thought he was in danger because prisoners were threatening him. He begged her to call the prison, which she did. But they never answered the phone so she had to leave a message, which mysteriously disappeared. I thought he was going to be safe in prison. I thought, ‘He’s got a bed, he’s being fed, he’s safe and being looked after.’ I never knew what horrors were happening in there. There was video footage of a group of men outside his cell door threatening him on the day he died. I do believe it got too much for him.” Chris’s mother Linda prefers to think it was a cry for help that was ignored. The jury at his inquest found that Chris was failed by the prison on numerous safeguarding fronts.

Linda talks about the Saturday evening two officers arrived at her home. “For liaison officers, they didn’t show much sympathy. They made me feel even worse because they said things like, ‘We’ve travelled all the way from Milton Keynes to give you the news’, as if I should feel grateful.”

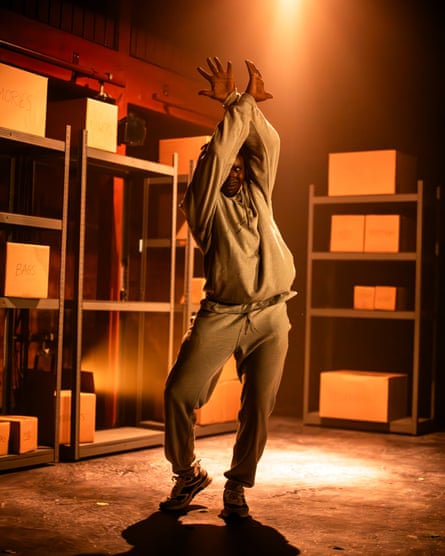

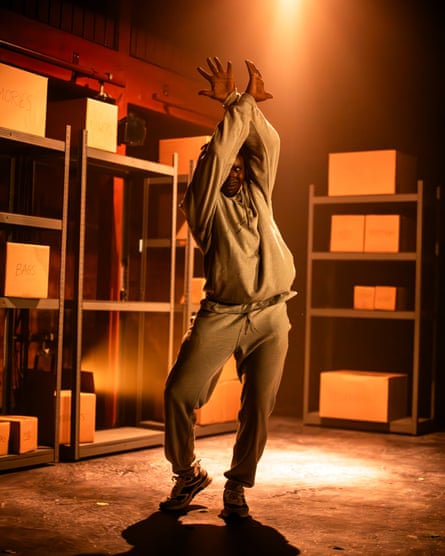

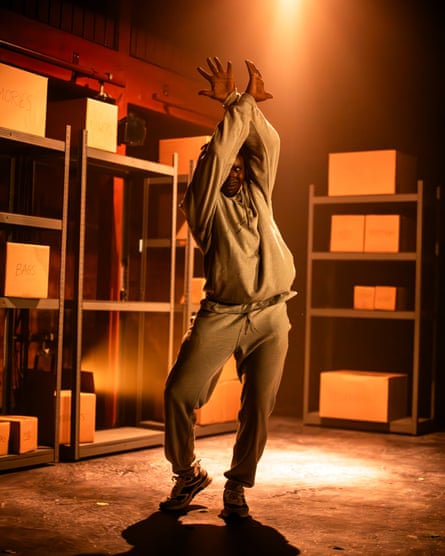

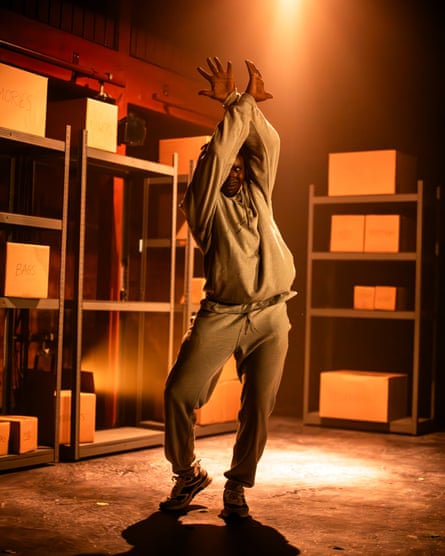

Despite its brutal subject matter, Woodhill’s script is astonishingly lyrical. Actors have been pre-recorded telling the families’ stories, with regular interjections from “experts”, while on stage four dancers (choreographed by Alexzandra Sarmiento, dance captain of the original London production of Hamilton) perform a gut-punching piece of physical theatre. Woodhead, who also directs, has never worked with dancers before, but he says it felt right here. “In one of our interviews, Janet says, ‘Who hasn’t done something wrong in their life? If you find me that person, I’ll show you a liar. For the grace of God, this could be your dance. It could be you.’” Not surprisingly, her words have stayed with him.

It also makes perfect sense to watch the dancers silently channelling the emotions of the prisoners and the bereaved. Both were silenced: nobody listened to the warnings of the prisoners or their loved ones, however loudly they screamed for help. Talking to the families, it soon becomes apparent that these losses had terrible repercussions. In the case of Stephen Farrar, it led to another tragedy: his brother Nathan never recovered from his death. In 2014, he died after a drugs overdose.

As for Chris Carpenter, Linda blames herself for not doing enough to support her son. “I know I failed him because I couldn’t handle his drinking.” She breaks down, weeping, and the weeping turns into wailing. “I know Carole thinks that I should have done more, and I don’t blame her. It’s something I will carry with me always. A part of me has died with him.”

There has been one positive for the families: they say working with Woodhead has been cathartic. I ask Carole and Linda how their relationship is now. “We’ve grown closer because of what we’re doing,” Linda says.

Woodhead has previously created verbatim plays with his partner Helen Monks about the alleged plot to infiltrate Birmingham schools with “hardline” Muslim teachers and governors (Trojan Horse) and a campaign against forced evictions (E15). He also co-created the verbatim play Chilcot with the Guardian’s former defence and security correspondent Richard Norton-Taylor. Like his previous dramas, he hopes Woodhill will educate and change opinions – in this case, showing audiences how our failing system is killing prisoners, many of whom shouldn’t have been jailed in the first place. Audiences will be asked to sign a petition to support the charity Inquest’s call for a national oversight mechanism to ensure recommendations made at inquests are followed up. In October, the accompanying short film will be screened at parliament.

A Prison Service spokesperson told the Guardian: “Our thoughts remain with the families of Chris Carpenter, Kevin Scarlett and Stephen Farrar. Over the past decade, we have made significant changes to improve mental health support at HMP Woodhill leading to a reduction in self-inflicted deaths.”

The families hope the play leads to better mental health support and more humane, safer jails. But they also want a better understanding of how so many people end up in jail. Chris’s mother Linda admits she used to prejudge prisoners. “I thought people deserved to be in prison because of what they did, and that it must be the family they came from. Having Chris, and knowing how he was and what happened to him in prison, has changed my view a hell of a lot. There’s just not enough help out there for their mental health, to give them the support they need. There’s no rehabilitation so they don’t reoffend.”

Sophia nods. “I want people to watch it,” she says, “and realise that these prisoners are humans with families, too.”

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.