On 5 January 1988, Tanya Smith – then two years into a 13-year prison sentence in West Virginia – walked out of her cell and kept on walking. Smith, who had been convicted of bank and wire fraud, wanted a shot at an appeal. Having grown increasingly desperate, she hatched an unorthodox plan to try to win her freedom from the outside. With the help of an accomplice, she disguised herself as a lawyer and floated confidently past the security guards who observed her every move.

Like many elements of Smith’s life story, it sounds as if it was ripped straight from the pages of a pulpy thriller. “When I reached the gate, I turned to the guard standing in the doorway and waved,” writes Smith in her action-packed memoir, Never Saw Me Coming. “He squinted as if he was seeing someone he knew … I smiled and waved again. A heavy lump formed in my throat … At any moment, someone could realise I was missing, and the alarm would sound.”

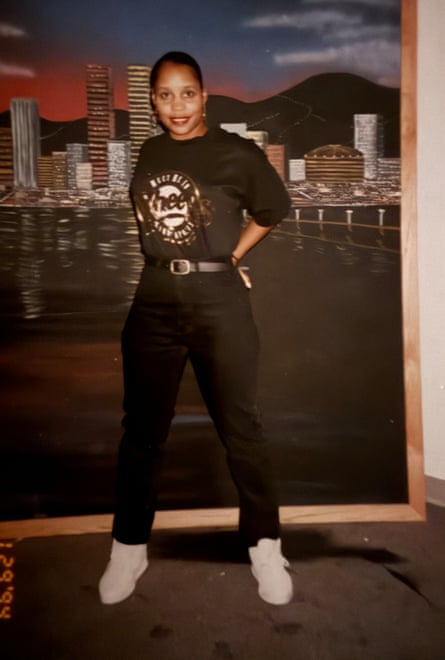

Despite her nerves, Smith says she knew her plan would work – and it did. Sitting now in the immaculate sage-green kitchen of her home just outside Los Angeles, the 64-year-old appears content and humble, in keeping with the book blurb that declares she is “enjoying the peace of suburban motherhood”. She tears up a few times during our call – when she thinks about the strained relationship she has with two of her three children, for example. But there are frequent flashes of the brilliance and confidence that helped her pull off a daring $40m scam that the FBI struggled for decades to unpick – and which they doubted a black woman could be capable of orchestrating.

After a while, I stop asking her whether she ever worried that any plan of hers wouldn’t work out, because the answer is always: “No.” As for her prison break, she says: “I wasn’t sure how I was gonna do it, but I knew I was gonna do it. I knew I’d figure out a way – I usually do. When my brain kicks in and there’s something I gotta do, I’ll make sure it happens.”

Never Saw Me Coming is the story of Smith’s rise to infamy, which eventually saw her cornered by the Secret Service and the FBI. She was handed down a string of considerable, seemingly vindictive sentences for the initial fraud, at a level almost unheard of for white-collar crime. When she was captured eight months after breaking out of prison, she was facing 24 years behind bars, thanks partly to being implicated separately in her ex’s crimes.

Smith’s early life couldn’t have been more sedate. She and her five siblings, including her identical twin sister, Taryn (not her real name, but the one Smith uses in the book), had a secure and loving upbringing on the north side of Minneapolis. Their parents had met while studying at a historically black, Christian university and became community leaders, her father opening a theatre that became a hub for black and working-class culture. Homeless and otherwise disadvantaged people were regularly welcomed into the family home.

“We were a very likable family, we had a lot of friends,” she says. “Our parents were always saying: the sky’s the limit! It was the best time of my life.” The Smith kids made many friends in the neighbourhood, including one Prince Rogers Nelson, who would of course become better known by his first name. “I would walk past the house and hear the drums go boom, boom, boom and the sound of the synthesiser. I knew he was talented, but I wasn’t thinking that one day he’d become this great big star.”

Like her father, Smith wanted to do something to help people, although – being a skint teenager – she had a slightly different way of going about things. Early in the book, she recounts tracking down a phone number that she believed belonged to the rising star Michael Jackson, only to get an earful from the ill-tempered Jackson patriarch, Joe.

Unperturbed, Smith turned her talent for finding phone numbers into a talent for tracking down money, pinballing her way from one bank department to the next, impersonating staff and figuring out how to get reserve funds transferred to people who needed it. “It gave me a natural high,” she says. “I felt like it was my duty to help.” Her voice begins to crack. “I wanted everyone to have a good life … the kids who couldn’t swim at the park when other kids could. I learned that there were people who had their electricity turned off, gas turned off, water turned off. How can you not help somebody who has kids and they can’t turn their stove on?”

Smith tried to help out her grandmother, sending her $5,000, but she assumed it was a bank error and didn’t touch the money. Helping people who were struggling felt “like being in Bewitched”, she says. “It was my favourite show as a child.”

Smith’s initial intentions might have been good, but she got in deep after discovering how to hack computers, slowly becoming the FBI’s worst nightmare – and landing those marathon prison sentences. Instead of sending money to real customers, she began sending the funds to accounts opened under fake names. The cash was then collected in person by a team of “runners”.

Initially, Smith knew her lackeys personally, but, as her operation grew, she began to hire them through intermediaries. Eventually, this unwieldy network would be her downfall: a runner got cold feet while withdrawing $160,000 at Caesars Palace casino in Las Vegas, telling staff that “a girl named Tanya” had asked him to pick up the money, eventually leading investigators to Smith.

As for Smith’s memoir, it ranges from darkly comic (Taryn and Tanya’s identical twin status becomes part of Smith’s legal defence) to tragic (she gives birth to two children in prison and is double-crossed so many times, even by her own lawyer, who was secretly working with federal prosecutors, that, were this a work of fiction, you would start to feel the writer had a vendetta against her).

While the prison break was a success (albeit temporarily), it put her back under the control of an abusive partner. Through it all, Smith remained determined to get her sentence reduced, propelled by her outrage at racist assumptions from FBI detectives. In the book, she recounts how one officer told her that “neeee-grroes murder, steal and rob, but they don’t have the brains to commit sophisticated crimes like this”.

It was, Smith says, “my turning point. That’s when everything changed for me. They hit my soul. I grew up in this household where I was told I could be anything I wanted to be, and for someone to tell you you couldn’t be who you are because of the colour of your skin … I realised I had to fight for other women, not just for me. I said to myself, I’m gonna show them exactly what this black woman can do.”

Smith was so appalled that she occasionally offered the detectives bait, via letters in which she declared herself “always 10 steps ahead of you”. “They used one of the letters in my trial, saying: oh, she’s cocky, she thinks she’s so smart,” Smith says with a laugh. “I wanted them to know it was me. You don’t tell me that I can’t be smart enough because I’m a black woman. I didn’t sign the letters – but I gladly dropped them in the mailbox.”

Smith writes about the cars and jewels she acquired with the money she stole (including a $50,000 diamond ring, which the jeweller hesitated to hand over to the black man who was working for Smith) and how she became the target of a convoluted plot to steal her ill-gotten fortune. Did she get a taste for the high life as the years went on and the sums of money she was siphoning off grew? “Absolutely! Yes!” she says, chuckling. “The more money I could have, the more things I could buy. You start realising the power of money and what it can do. I was still helping others – it wasn’t just for myself. But I did buy things and I did enjoy it. I mean, luxury’s nice!”

Today, Smith is upbeat and clearly relishing the opportunity to share her gripping story, but much of her time in prison was anything but fun. In the book, she recounts the strain her conviction had on her family and how “the sadness on my father’s face when they ushered me out of the courtroom made me wonder how things had ended up like this”. In the beginning, she writes: “I had just wanted to help people … But step-by-step I’d gone elsewhere, and now we were both paying for it.”

She describes her life of crime as “ultimately destructive” and writes of her “tremendous guilt and some regret over losing nearly a quarter of my life to prison”. There is a pained quality to her voice when she speaks about the two children, then 11 and 13, who were practically strangers to her when she was released from prison; the breakdown of her relationship with Taryn; and returning to a family unit that felt incomplete (her parents died while she was inside). “My mom and dad were gone, so it was very different. They were my backbone, they were my strength, they were everything,” she says.

But, in many ways, Smith had become the source of strength she was looking for. Rather than brazenly walking out, as she had done on that January morning – only to be apprehended once again – she found legal means to get out of prison, poring over library law textbooks until she found terms and precedents that showed she was long overdue for release. She came across the concept of “same course of conduct”, which meant that, had her crimes been treated as part of a spree, rather than individual offences, she would never have ended up with the vast sentence that she did. After a protracted legal battle, she was released on 27 May 1999.

A year before her 40th birthday, the next act of Smith’s life began. She had another daughter, Makala, whose childhood she could more readily enjoy. “She’s the joy of my life,” she says. “It’s almost like I lost my children … so when Makala came along, I had a new chance.” Smith starts to wipe her eyes again. “She’s wonderful. We have a great relationship. I look at her sometimes and I’m like: you’re everything I could’ve wanted.”

It was Makala who wrote about her mother’s life for her college admissions essay and in turn encouraged Smith to write about her past, which she had kept hidden from almost everyone she had met in the years since her release. In California, she says, “I just started my life over … it was very hard for me, but I never let anyone see that. I was just the mom who would sing Hannah Montana in the Honda with all the neighbourhood kids, taking them to the zoo, to the movies. I always had a smile on my face, but inside it was different. I felt like I couldn’t talk about being in prison because people would ostracise me – people would just be like: ‘I don’t want to be around you, I don’t want you around my kids.’”

Eventually, four years ago, Makala convinced her mother that her story might be a source of inspiration to others, so she set to work. Smith says the process helped her to shed the worries she had been hanging on to since she left prison. “When I started writing this book, that’s when I started to feel like I was free – it’s like a burden has been lifted, being able to talk to people. I’m emancipated.” Instead of the fake name she used for the past two decades, she is now known to friends as Tanya Smith again.

When it came to getting her work in front of a literary agent, she employed one more (legal) trick that the young Smith would have been proud of. “I went through this book of all the different agents and agencies. I said: I’m gonna get everybody’s number and send a message straight to their cell phone [telling them about the project]. I sent it to around 15 literary agents and all of them said: ‘We want to represent you.’”

A potential Netflix series didn’t get off the ground. Smith can’t go into much detail, but relations remain warm with Issa Rae, the showrunner of Insecure who was slated to produce and has described Smith as “my hero”. Smith says there has been plenty of interest since; it’s surely only a matter of time before her story ends up on our screens. In the meantime, she has more work to do. “There was so much stuff in the book we had to cut; it would have been too long,” she says. “But I’m writing a second one …”

Never Saw Me Coming by Tanya Smith is out now (Quercus, £20). To support the Guardian and the Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.