Myanmar has undertaken a vast and secretive prison-building programme, according to new satellite analysis, prompting fears it has been carried out to jail thousands of pro-democracy protesters.

Analysis of the images taken before the February 2021 military coup – which ousted the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi – through to January 2024, indicate that 27 of 59 prisons identified in the south-east Asian country showed signs of large-scale expansion or the construction of new wings or buildings.

Officially undeclared by the ruling military, the extensive prison building programme has prompted fresh disquiet that Myanmar’s jail network is an increasingly central part of the ongoing crackdown against the nation’s pro-democracy movement.

More than 25,900 “political prisoners” have been arrested since the 2021 coup with almost 20,000 still detained, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners – which keeps a toll of those killed, jailed or detained by the military.

Published to mark the third anniversary of the 1 February military coup, the analysis, carried out by Myanmar Witness, which collates and verifies evidence of human rights abuse, also detected that 33 new structures likely to house inmates have since been erected outside the perimeter of 25 prisons.

“Due to the security surrounding these additions, and factors such as location and their high-security structure, we believe they are new detention facilities connected to the official prisons,” said Matt Lawrence, director of Myanmar Witness, which is run by the London-based Centre for Information Resilience, a research body partly funded by the British government.

The study also identified an apparent proliferation of 53 labour camps, mainly quarry sites and agriculture projects in rural areas, of which almost all exhibited signs of continuous activity.

The post-coup expansion of the prison system has coincided with the mass arrests of political opponents, journalists and activists.

The most high-profile is Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s de facto civilian leader who was arrested in a pre-dawn raid at the start of the coup, prompting fears she might be taken to Insein prison in Yangon City where she was held in 2003 and 2009.

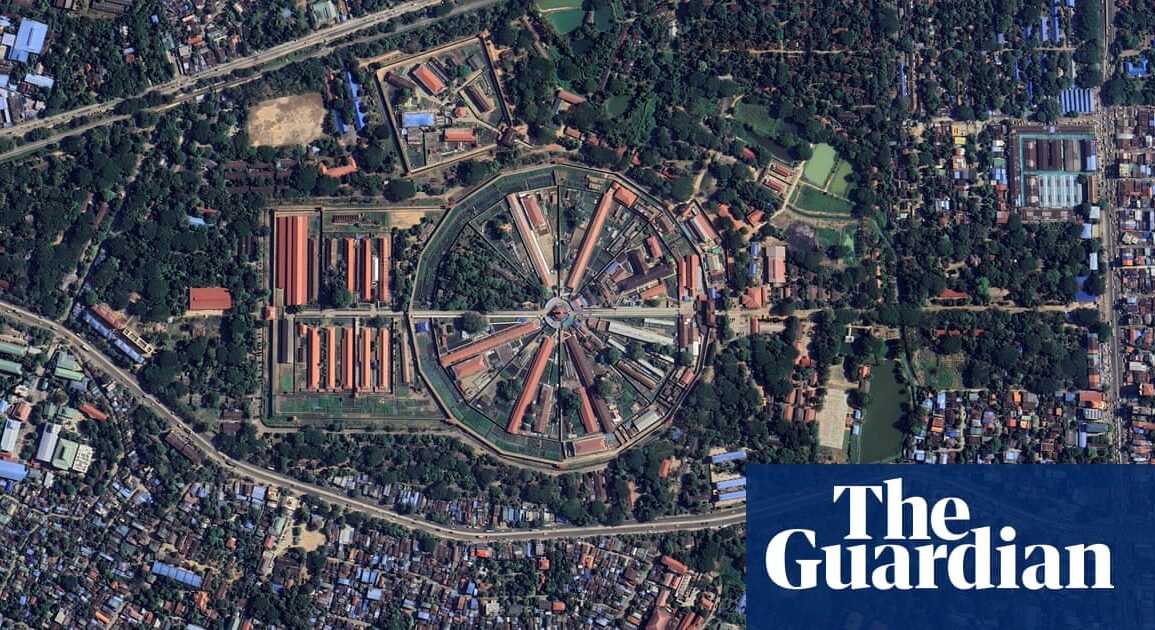

Probably the country’s most notorious jail, Insein’s distinctive radial design was constructed by British colonisers in 1887.

In July 2022, Insein drew international headlines when four democracy activists were executed inside the prison, the first use of capital punishment in the country for decades.

Accused of committing “terror acts” in a closed-door trial that human rights groups labelled unjust, the analysis appears to pinpoint the location of the gallows used during the infamous executions.

Using open source images, Myanmar Witness says a small roofless structure visible in March 2022, and situated just inside the prison’s original perimeter wall, was possibly the site of the killings, as subsequent images show it was later upgraded and fitted with a new blue roof. Activists believe this may have been to obscure the gallows from surveillance.

Suu Kyi, however, has so far avoided being held within Insein. Instead, Myanmar’s civilian leader was taken to the modern Naypyidaw prison, constructed just outside the newly built military capital of Naypyidaw.

Again, Naypyidaw prison appears to have received significant investment during the last three years with large new buildings appearing inside and outside its perimeter.

A year into the coup, in February 2022, several new buildings appear at the site. Later, in images dated April 2023, further additions materialise just north of the prison’s gatehouse.

Some prisoners, including Suu Kyi, were kept in solitary confinement while inside Naypyidaw, though reports suggest the 78-year-old was moved to house arrest in July 2023.

The analysis also identifies two entirely new prisons built since the coup. One of these, geolocated in Mawlamyine township, Mon state, has been the subject of local reports indicating it will hold political prisoners and be solely run by the Myanmar military, rather than its prisons department. Since February 2022, satellite imagery has captured building works at the site.

Although the analysis mapped more than 100 jails and labour camps in total, Lawrence said it was likely that the true expansion of Myanmar’s prison estate was far more extensive than they had managed to establish.

He said: “Our methodology may well underestimate the expansion of prisoner accommodation. Open source data does not allow us to see inside every new building nor ascertain what every block is used for.”

Contemporary accounts detailing conditions have described hunger strikes, prisoner beatings and sexual violence alongside claims of overcrowding due to the high number of political prisoners detained.

At the start of the year in what has become an annual ritual, Myanmar’s military government ordered the mass pardon of thousands of inmates, including 114 foreigners. However, there is no sign that Suu Kyi – who has been seen once since her arrest, inside a spartan Naypyidaw courtroom – will be freed.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.