Two decades before founding the American Red Cross, Clara Barton was a humanitarian without a cause.

A former schoolteacher working as a clerk for the U.S. Patent Office in Washington, D.C., Barton would find it during the Civil War. A week after Fort Sumter was attacked, Confederate sympathizers assaulted a Union regiment from Massachusetts, Barton’s home state, near Baltimore. The unit included some of her former students.

Four of those students died in the attack, and the casualties were transported to the Capitol, where Barton found the wounded “literally lying in the Senate chambers, but there is no one there to care for them,” according to the American Heroes Channel.

That incident inspired Barton, who lacked formal medical training, to comfort wounded soldiers throughout the war — tending to their injuries, reading to them and helping them write to their loved ones. She became known as the Angel of the Battlefield.

In early 1865, Barton began caring for two ill family members — her brother, Stephen, and her nephew, Irving Vassall.

“Vassall, a government employee, had heard news that exchanged Union prisoners were returning in poor condition and that the government needed help notifying the relatives of those who were missing or had died in captivity,” according to the Clara Barton Museum. “Vassall relayed the information to Barton in the hope that she might be able to offer assistance.”

During the Civil War, no official method existed to document the whereabouts of missing or dead soldiers, making some degree of closure painstakingly difficult to achieve in most instances. Barton was undeterred, and with the blessing of President Abraham Lincoln, she opened the Bureau of Records of Missing Men of the Armies of the United States — a long-winded name shortened to the Missing Soldiers Office — in 1865.

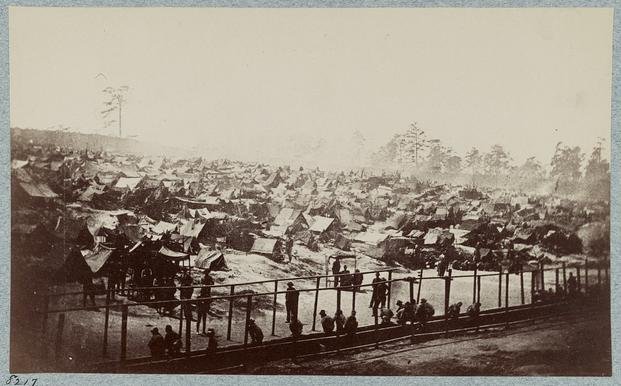

The most fruit from the efforts of Barton and others was borne from revealing what happened at an infamous Confederate prison in Georgia called Andersonville. Constructed in 1864 nearly a hundred miles south of Atlanta, Andersonville was the largest of the 150 military prisons maintained during the Civil War, and its reputation was deservedly the worst.

As many as 45,000 Union troops were imprisoned at Andersonville during its 14 months of operation. They were treated terribly, as “nearly a third of them would die within the walls due to the poor sanitation, lack of food, widespread disease, and brutal conditions,” a 2021 blog post from the Library of Congress notes.

The inhumane suffering that occurred at Andersonville might have been lost to history if not for Dorence Atwater, a Union prisoner who helped bury the dead there; “he kept a list of their names and location of their gravesites for the prison wardens,” according to the Department of Veterans Affairs. Armed with copies of those lists that he surreptitiously took with him after his release, Atwater contacted Barton after seeing the first of five Rolls of Missing Men that the Missing Soldiers Office would publish.

That initial list included more than 1,500 names.

“The appearance of a man’s name upon my roll is simply evidence that some friend is asking for him … and the non-appearance signifies that he has not been inquired for, or there has not been time to get his name upon a roll,” Barton said at the time.

In mid-1865, Barton and Atwater traveled to Andersonville on an Army expedition. As Atwater and other former soldiers recorded the graves of more than 13,000 men and marked them with headstones, Barton wrote letters to their families. After their work was complete, “Barton was given the honor of raising the American flag for the first time over the recently established Andersonville National Cemetery,” the National Park Service said.

After Andersonville, the Missing Soldiers Office faced a financial crisis. Barton was still solely bankrolling the efforts, refusing to take donations “on a matter of principle” and not accepting money from relatives seeking information about missing soldiers. The office remained open, thanks to congressional approval of $15,000 (equivalent to roughly $300,000 in 2023 dollars) to reimburse Barton for past expenses and to continue her work.

The Missing Soldiers Office closed in 1868, leaving behind an impressive level of accomplishment, according to Stephen B. Oates, author of “Woman of Valor: Clara Barton and the Civil War“. The office received more than 63,000 inquiries, identified 22,000 soldiers, disseminated 99,000 copies of the Rolls of Missing Men and wrote nearly 42,000 letters.

“If it has been my privilege to lighten ever so little the heavy burden of grief which has been laid upon the hearts of our suffering people, or throw the feeble weight of my arm on the side of my country in her hour of trail, if I have made one heart stronger, or one war less bitter, I regard it as a blessing forever beyond my power to express,” Barton wrote.

Exhausted from her efforts — Barton kept her job at the Patent Office during this time — her physician advised her to travel to Europe to relax. While overseas, Barton became familiar with the international Red Cross movement to aid those injured in war. She founded the American Red Cross in 1881 and served as its president until 1904.

Barton died on April 12, 1912, at the age of 90.

— Stephen Ruiz can be reached at stephen.ruiz@military.com.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.