Former penitentiary now teaches tourists about the danger of locking up too many people

Last month I was in America and visited Philadelphia, an hour and a half by train from New York. I was surprised to find a prison, now closed to prisoners and open to the public, which had been built in the 1820s. Since it was walking distance from the centre of town, I decided to pay it a visit. The UK’s Victorian prisons are well known: 32 are still in use, housing 22,000 people, over a quarter of the prison population.

London’s Pentonville, built in 1842, is one of the earliest, followed by others such as Brixton, Wormwood Scrubs, Wandsworth and more all over the British Isles, many in cities. In one 35-year period, 1842 to 1877, 90 were built, often on the famous hub spoke layout.

But the Eastern State Penitentiary was built before any of these. How was it that this new country, only founded in the late eighteenth century after throwing off English colonialism, had created a new prison system? Was it a determination to stamp out crime by locking up the perpetrators, what the Victorians came to describe as ‘Hard fare, hard labour, hard bed’?

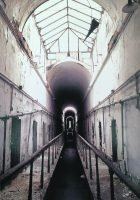

I set out walking through avenues and into a residential area that had grown up many decades after the prison. Eventually, at the end of a quiet road, I sighted a fearsome-looking castle, complete with battlements, turrets, and archery slits for windows. In I went, already thinking I had the answer to my question. My first walk down stone corridors with doors to cells on either side seemed about the usual punishment, even if I half noticed that the cells were large, the building elegantly domed, a mattress on a bed, and what looked like a radiator, near a lavatory and running water.

As I paid more attention to the guide on my earphones, I learnt that this early prison was an experiment with the highest ambitions. It was the brainchild of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating of Miseries of Public Prisons. It was called Penitentiary because the founder wanted the men (women joined later) to become penitent of their failings and follow a better path, helping themselves and society. The fearsome castle was actually a fake, the castellation was too low to hide behind, and the slit windows were just for show, not even cut all the way through.

The planning inside was to give the prisoners a level of comfort that many would not have been used to. Indeed, there was central heating, only one person to a cell, sanitation, and purposeful activity available such as learning to make shoes. And the buildings with their high-domed ceilings were elegant rather than depressing. People came from around the world to see this experiment.

There was, however, a downside. The founders believed that only in solitude would a sinner face his sins and find the strength to renew his soul. They believed in the innate goodness of mankind who had been led astray by adverse circumstances. Religion was, after all, an important part of the story of independent America. The rule of segregation of one prisoner from another, and even from warders, was so strong that in the short periods the men were outside their cells, they were forced to wear hooded masks.

The English author, Charles Dickens, visiting like others in 1842, noted that “The regime is rigid, strict and hopeless solitary confinement, and I believe it in its effects to be cruel and wrong.”

His views did not prevail at the time. Indeed England, following the 1865 Prisons Act, put in place what was called the Silent System. In this case, it advocated at the same time harsh penalties and hard labour.

But all the ideals in the world were eventually worn down by human nature and by the beginning of the twentieth century the State Penitentiary had begun a very different regime, with joint work, exercise, and a well-staffed hospital. It also became much bigger, with new wings, housing far more men and women, crowded into smaller cells. By 1911 there were 885 residents.

Surprisingly, some of these were dogs, including, most famously, Pep, a black Labrador retriever. C2559 was sentenced to life for the murder of the Governor’s cat. He became a valued member of the prison community.

Meanwhile the hospital, somewhat imaginatively, offered face-changing operations to make the patient appear no longer threatening and even charming. Less dramatically, Al Capone, the notorious Chicago gangster, had his tonsils out in 1929 while he was living there in a comfortable cell more like a living room. The story went that his eight-month stay was to avoid the repercussions of the St. Valentine’s Day massacre, where he’d arranged the deaths of rival bosses. When he departed, he chose the back door to avoid his hundreds of fans waiting at the front.

The reality was that the Penitentiary had become like any other large prison, overcrowded, with warders dealing with escapes, riots, and in-house murders. Soul-searching was little in evidence and eventually it was shut down in 1971. For 20 years it was left to moulder, only inhabited by teams of feral cats, and gradually losing the fight against nature’s marauding shrubs and trees.

So this might all end as a story of high ideals coming to nothing. But as I walked out into the old exercise yard, I was faced with a tall red structure on which, as I came closer, I read the dire statistics of the prison population in the US. During the past four decades the rate of incarceration has more than quadrupled. Roughly 1.8 million were incarcerated at the end of 2023, plus 803,000 on parole and 2.9 million on probation. The more detailed figures I saw at the Penitentiary are updated regularly. It is a fact that America imprisons more people per head than China.

Tourists to Philadelphia – lured out to the Penitentiary to enjoy the re-staging of the Fall of the Bastille or the spine-chilling drama ‘Terror in the Night’ – can hardly avoid the facts of modern prison policy. Furthermore, an exhibition off the yard vividly explains not only the reasons, primarily longer sentences and more crimes punishable by prison, but also the grim effects of such a heavy penal policy.

So this prison, started with the highest motives, has come full circle and is now trying with the facts and figures and the real stories of real people’s experiences to educate the wider world. It seems likely that anyone who has just walked through the crumbling halls and cells of this prison, once crammed with the incarcerated, will have imagined for at least a few minutes what it felt like to live there for years. And this imaginative exercise might make them more open to learning about what modern America offers their incarcerated fellow citizens. Not just for the thrill of terror and relief that they have escaped such a fate, but to understand a bit more about why and how it happens and to consider whether locking up more and more people in prison is the right way to go.

The experience reminded me of my own visit some years ago to Reading Gaol, then recently discontinued as a prison. As I stood in Oscar Wilde’s cell, I pictured Wilde writing his great poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, and the fact that his crime, homosexual acts, was eventually legalised in 1968. Since the prison was closed in 2013, it has stood empty, costing the MoJ between £2 million and £3 million to keep in repair. Efforts were made to turn it into an arts centre.

In January this year, it was finally sold to a Chinese company, Ziran Education Foundation. Last month they announced plans for a hotel, gallery and unspecified ‘museum’. After my visit to the Eastern State Penitentiary, it seems even more obvious that at least part of Reading Gaol should be a permanent prison learning centre, arts too, perhaps a school. Leading people towards a greater understanding of the historical and present effect of making long-term imprisonment central to our system of punishment would be a hugely important achievement.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.

A once ‘elegant’ wing

A once ‘elegant’ wing