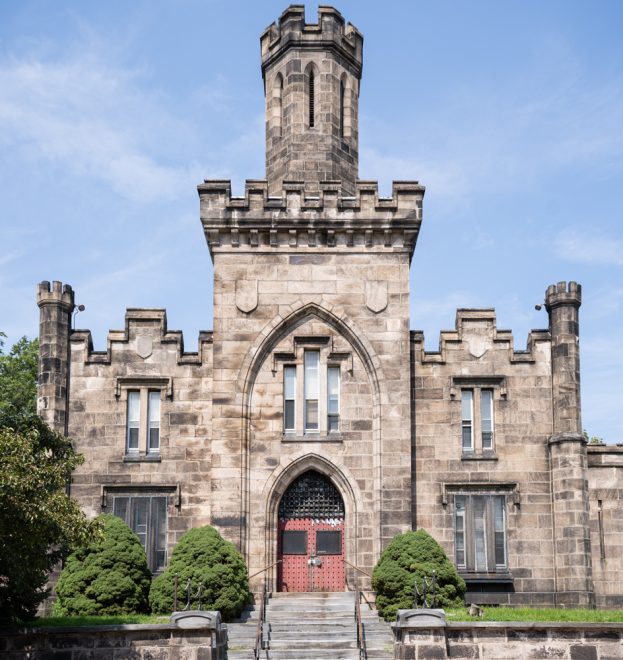

Montgomery County/Airy Street Prison in Norristown is slated for demolition. | Photo: Michael Bixler

Consider two prisons, both built in the mid-1800s century, both imposing, head-turning historical relics of their respective neighborhoods. The first is a welcome attraction: Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary, a popular, thriving museum and the backdrop of bustling Fairmount Avenue. The second: Norristown’s old Montgomery County/Airy Street Prison, a vacant, neglected building in the middle of town doomed by a date with the wrecking ball, save for an unlikely 11th-hour intervention.

Peggy Dellisanti loves them both. Growing up in Philadelphia’s Fairmount neighborhood in the 1950s and 1960s, her family didn’t have much. But what they did have was the cultural and architectural richness of that section of the city, where the kids played in the fountains of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and thought the massive penitentiary was their very own neighborhood castle.

As a young woman, Dellisanti boarded a train from Philly to Norristown to pursue a business opportunity that would lead to her opening a boutique clothing shop. Walking Norristown’s streets, she was smitten by the then-borough’s main business district. Then, up ahead, she saw another castle-like structure right at the crest of the road. Airy Street Prison, or as she calls it, “The Queen on the Hill.”

Half of a century later, as many of the buildings and institutions from the heyday of Norristown have faded away, she dreads the thought of losing it, too. After decades of the prison sitting idle and deteriorating, commissioners for Montgomery County, which owns the property, approved in July a contract to tear it down. And if Norristown, a municipality, follows through by issuing a demolition permit? “I think you lose the only piece of historical beauty in the heart of town,” Dellisanti said. “To me, it would be like tearing down a cathedral or burning a Piccaso.”

Montgomery County officials don’t see it that way. After decades of disinvestment, development is finally catching on in the county seat of Norristown. Megan Alt, Montgomery County’s communications director, said the prison is in a state of disrepair, and unlike other historic properties, the county doesn’t believe this one is worth saving. “We are not willing to ask taxpayers to spend millions of dollars to preserve a monument to a system of incarceration. Taking down this structure will not change the inequities in our criminal justice system, but we also refuse to invest in celebrating that legacy,” said Alt. “Our record shows that we respect and endorse historic preservation, and we also want to continue to contribute to Norristown’s future.”

A LeBrun Masterpiece

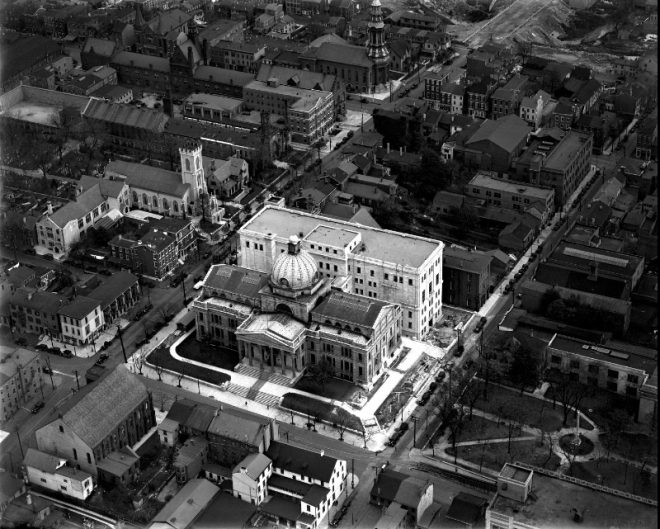

Built in 1851 by architect Napoleon LeBrun, admirers of the prison at 35 E. Airy Street in Norristown call it a masterpiece. That was the word used in a 1984 nomination to the National Register of Historic Places for Norristown’s Central Historic District, which includes the prison along with various other properties. According to the nomination, Norristown was a place of government institutions from its start. In 1784, Montgomery County was created out of Philadelphia County, and a 27.5-acre parcel of land in what is now Norristown was designated for the seat of county government, “making it one of the earliest established” in Pennsylvania. Norristown Borough was formally organized in 1812 (it would become a municipality in 1986), and encompassed about 250 acres. In 1852, it expanded on another 2,000 acres to reach its present day footprint.

Paralleling the geographic growth of Norristown was that of its institutions, with the county leading the way. Montgomery County’s first courthouse was built in 1791, with a prison following. By the mid-19th century both were upgraded, with the construction of the current prison on Airy Street in 1851 and the nearby county courthouse at Airy and Swede Streets in 1854. Both were designed by LeBrun, an architect most notable in Philadelphia for his designs of St. Augustine’s Church, the Cathedral-Basilica of Sts. Peter and Paul, and the Philadelphia Academy of Music.

“Like the courthouse, the original prison was replaced with a more impressive structure, the 1851 masterpiece by architect Napoleon LeBrun,” the 1984 nomination reads. “Both buildings continue to dominate the [Norristown] Central district today; the prison, in particular, exhibiting noteworthy architectural integrity.”

But nearly 40 years later, some say the building’s condition has deteriorated. The prison closed in 1986 according to Doug Seiler, an architect, supporter of the prison’s preservation, and member of Norristown’s Historical Architectural Review Board. The Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office for a time utilized the rear of the long, rectangular shaped building for auxiliary functions, but eventually it was left entirely abandoned. The fact that the building has been left largely untouched both contributes to its beauty and is the bane of its existence.

An arial view from the 1960s of the Montgomery County Courthouse that was built between 1852-56 and designed by architect Napoleon LeBrun. | Photo courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia

Seiler says he was last in the prison about six years ago after a group of paranormal investigators received permission to go inside. “You walk in the front door and you go straight back past some jail cells, and it ends in a great big room where you have a blockbuster space,” Seiler said. “It ends in this big 1890s huge room that has steel cages within the brick building that’s like three tiers. It’s got these doors where one big lever shuts a whole side of doors on one level.”

Seiler said the space is like a time capsule, with pictures, cots, and calendars from prisoners still adorning the cells. “It’s like they just walked out,” explained Seiler.

The Gothic front facade of the building appears to still be very much intact. Its spires, turrets, and slits directly recall a medieval castle, a design for which “LeBrun drew on John Haviland’s landmark Eastern State Penitentiary,” according to the Society of Architectural Historians.

However, there is no doubt that the building has serious problems. Seiler said there are issues with some stone work including in-grown tree vegetation. Portions are crumbling, Seiler observed. Alt said there was a partial roof collapse in 2019. As with virtually all old buildings, asbestos is present and would require remediation.

Past efforts at repurposing the building also failed. Seiler and other admirers of the building said there have been various proposals and studies for reuse over the decades, including housing, a hotel, a museum, a cultural center, and an annex of the Elmwood Park Zoo, perhaps as an insectarium. But for various reasons, none came to fruition.

Last Hope for Preservation

Some locals would prefer that the prison be adaptively reused, rather than razed for redevelopment. | Photo: Michael Bixler

Even in the building’s 11th hour, some hold out hope an adaptive reuse still can be achieved. Seiler thinks the building lends itself perfectly to a museum use, with small exhibits in the front before opening into a main exhibition toward the rear. According to Seiler, the county could spend a portion of the nearly $1 million budgeted for the building’s demolition to instead knock down or repair its worst segments and try to entice a real estate developer. “If no one shows up, then tear down the rest,” Seiler said. He has heard word for about six months that the county, which has continuously owned the prison since its opening, was planning to tear it down. That became official on July 20 when county commissioners agreed to pay $994,376 to Tamco Construction of Doylestown to demolish the prison. That triggered the latest round of grassroots support for the building, with proponents of reuse starting an online petition and publishing op-eds in local media.

But the county doesn’t seem intent on exploring other options. In a 1987 article in the Allentown Morning Call, Montgomery County officials at the time said they wanted to see the building reused. Then-county commissioner Paul B. Bartle told the newspaper that potential office-focused plans had been explored, but were “put on hold.” The article also noted that Bucks County had solved a similar problem by placing a new cultural arts complex in a shuttered jail. But Bartle told The Morning Call that Montgomery County commissioners “feel we want to hold the prison for the future of the county and not let that space go,” adding they wanted to see at least its front facade retained.

Today, current county leaders are singing a different tune. “The prison is a crumbling, environmentally hazardous structure that represents a history of incarceration that should not be the face of Montgomery County or its county seat,” Alt wrote in an email. “We are excited at the prospect of working with Norristown to repurpose the prison property and the neighboring Airy Street parking lot to further spur the municipality’s revitalization and benefit the entire community.” Alt also pushed back on the idea that the county is insensitive to historic preservation, adding that it is “investing over $90 million to architecturally restore the historic Montgomery County Court House.”

The potential last defensible ground for admirers of the building lies within Norristown’s municipal government, which holds final authority on issuing demolition permits. Seiler said it is his understanding that the application for a demolition permit has already been requested. By code, it will automatically be reviewed by the city’s Historical Architectural Review Board.

Seiler explained that there is language in the code that would potentially allow the board to initiate a delay on the demolition while it tries to garner support for an alternative plan. The board’s next meets on Wednesday, August 23, and the application will be on the docket.

Crandall Jones, Norristown’s municipal administrator, said the review board will be tasked with making a recommendation to the township’s seven-member municipal council. Council would then vote to approve or disapprove the board’s recommendation The council’s next planned meetings are September 5 and 19.

It is unclear where council members stand. Council president Thomas Lepera only offered brief comment via email in which he said it would be “much more beneficial if you were to reach out to the county seeing that they are in fact the owner of the property.” Preservationists who attended a council meeting on August 15 claim Lepera made similar comments and also said they would have to find private money to support any effort to preserve the building.

Seiler, who has advocated for the building for decades, said he has grown weary over time. Still, he, Dellisanti, and others will be looking for any out they can find to save the prison until demolition day arrives. “I really hope there is a way they can prevent that wrecking ball from taking the building down because of its historic value,” said Dellisanti, recalling the loss of other historic buildings in Norristown, like the art deco Norris Theatre, opened in 1930 and demolished in 1983 for a McDonald’s. “I just don’t understand how that can even happen. I just don’t get it.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.