A hidden path to America’s dinner tables begins at an unlikely source: a former Southern slave plantation that is now the country’s largest maximum-security prison.

Unmarked trucks packed with prison-raised cattle roll out of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, where men are sentenced to hard labor and forced to work for pennies per hour, or sometimes nothing at all.

After rumbling down a country road to an auction house, the cows are bought by a local rancher and then brought 600 miles to a Texas slaughterhouse that feeds into the supply chains of giants like McDonald’s, Walmart and Cargill.

Intricate, invisible webs like this one link some of the world’s largest food companies and most popular brands to jobs performed by U.S. prisoners nationwide, according to The Associated Press’ sweeping two-year investigation into prison labor that tied hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of agricultural products to goods sold on the open market.

The goods these prisoners produce wind up in the supply chains of a dizzying array of products found in most American kitchens, from Frosted Flakes cereal and Ball Park hot dogs to Gold Medal flour, Coca-Cola and Riceland rice. They are on the shelves of virtually every supermarket in the country, including Kroger, Target, Aldi and Whole Foods. And some goods are exported, including to countries that have had products blocked from entering the U.S. for using forced or prison labor, like China.

People locked up in the U.S. are among America’s most vulnerable laborers. If they refuse to work, some can jeopardize their chances of parole or face punishment, like being sent to solitary confinement. They also are often excluded from protections guaranteed to almost all other full-time workers, even when they are seriously injured or killed on the job.

That means companies tapping into this cheap, reliable workforce often don’t have to worry about official complaints over poor conditions, all while the companies can possibly get tax credits or other financial incentives.

The rise of prison labor

The number of people behind bars in the United States started to soar in the 1970s, disproportionately affecting people of color. With about 2 million people locked up, U.S. prison labor from all sectors has morphed into a multibillion-dollar empire, extending far beyond the classic images of prisoners stamping license plates, working on road crews or battling wildfires.

Though almost every state has some kind of farming program, agriculture represents only a small fraction of the overall prison workforce. Still, an analysis of data amassed by the AP from correctional facilities nationwide traced nearly $200 million worth of sales of farmed goods and livestock to businesses over the past six years — a conservative figure that does not include tens of millions more in sales to state and government entities. Much of the data provided was incomplete, though it was clear that the biggest revenues came from sprawling operations in the South and leasing out prisoners to companies.

The biggest prison farm operations remain in the South, and crops are still harvested on a number of former slave plantations, including in Arkansas, Texas and at Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Farm. Those states, along with Florida, Alabama, South Carolina and Georgia, pay nothing for most types of work.

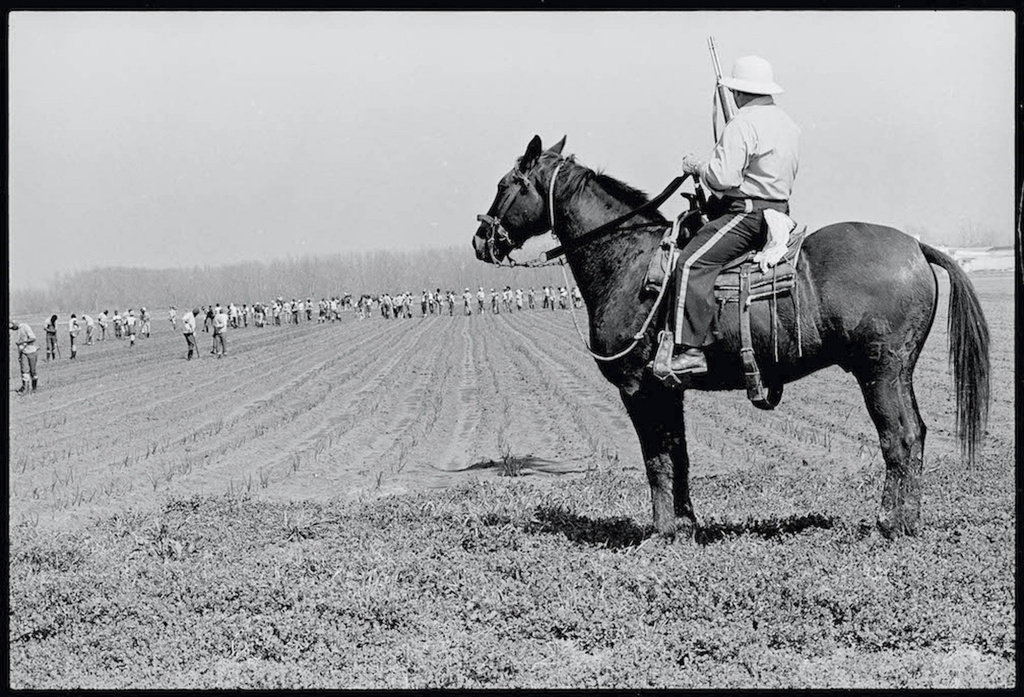

Some prisoners work on the same plantation soil where slaves harvested cotton, tobacco and sugarcane more than 150 years ago, with some present-day images looking eerily similar to the past.

In Louisiana, which has one of the country’s highest incarceration rates, men working on the “farm line” still stoop over crops stretching far into the distance.

Willie Ingram picked everything from cotton to okra during his 51 years in the state penitentiary, better known as Angola.

AP / A prison guard keeping watch over prisoners working in a field at the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

AP / A prison guard keeping watch over prisoners working in a field at the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

The so-called “Alcatraz of the South” spans 18,000 acres, surrounded by crocodile-infested swamps in a bend of the Mississippi River.

The former 19th-century antebellum plantation once was owned by one of the largest slave traders in the U.S. Today, it houses some 3,800 men behind its razor-wire walls, about 65% of them Black. Within days of arrival, they typically head to the fields, sometimes using hoes and shovels or picking crops by hand. They initially work for free, but then can earn between 2 cents and 40 cents an hour.

During his time in the fields, Ingram was overseen by armed guards on horseback and recalled seeing men, working with little or no water, passing out in triple-digit heat. Some days, he said, workers would throw their tools in the air to protest, despite knowing the potential consequences.

“They’d come, maybe four in the truck, shields over their face, billy clubs, and they’d beat you right there in the field. They beat you, handcuff you and beat you again,” Ingram said.

Louisiana corrections spokesman Ken Pastorick told the AP Angola has been transformed from “the bloodiest prison in America” over the past several decades with “large-scale criminal justice reforms and reinvestment into the creation of rehabilitation, vocational and educational programs designed to help individuals better themselves and successfully return to communities.” He noted that pay rates are set by state statute.

For many states, work-release programs have become huge cash generators, largely because of low overhead. In Alabama, for instance, the state brought in more than $32 million in the past five fiscal years after garnishing 40% of prisoners’ wages.

In Louisiana, where more than 1,200 companies hire prisoners through work release, sheriffs get anywhere from about $10 to $20 a day for each state prisoner they house in local jails to help ease overcrowding. And they can deduct more than half of the wages earned by those contracted out to companies — a huge revenue stream for small counties.

Current and former prisoners in both Louisiana and Alabama have filed class-action lawsuits in the past four months saying they have been forced to provide cheap or free labor to those states and outside companies, a practice they also described as slavery.

Companies and goods involved in the prison workforce

While prison labor seeps into the supply chains of some companies through third-party suppliers without them knowing, others buy direct. Mammoth commodity traders that are essential to feeding the globe like Cargill, Bunge, Louis Dreyfus, Archer Daniels Midland and Consolidated Grain and Barge — which together post annual revenues of more than $400 billion — have in recent years scooped up millions of dollars’ worth of soy, corn and wheat straight from prisons, which compete with local farmers.

Big-ticket items like row crops and livestock are sold on the open market, with profits fed back into agriculture programs. For instance, about a dozen state prison farms, including operations in Texas, Virginia, Kentucky and Montana, have sold more than $60 million worth of cattle since 2018.

As with other sales, the custody of cows can take a serpentine route. Because they often are sold online at auction houses or to stockyards, it can be almost impossible to determine where the beef eventually ends up.

In one instance in Louisiana, more than 80 cattle raised by prisoners left a state penitentiary to go to an auction, where a local livestock dealer bought the lot then sold the cattle to a Texas beef processor that also buys cows directly from state prisons. Meat from the slaughterhouse winds up in the supply chains of some of the country’s biggest fast-food chains, supermarkets and meat exporters, including Burger King, Sam’s Club and Tyson Foods.

And in addition to giant farms, at least 650 correctional facilities nationwide have prisoners doing jobs like landscaping, tending greenhouses and gardens, raising livestock, beekeeping and even fish farming, said Joshua Sbicca, director of the Prison Agriculture Lab at Colorado State University. He noted that corrections officials exert power by deciding who deserves trade-building jobs like welding, for example, and who works in the fields.

In several states, along with raising chickens, cows and hogs, corrections departments have their own processing plants, dairies and canneries. But many states also hire out prisoners to do that same work at big private companies.

The AP met women in Mississippi locked up at restitution centers, the equivalent of debtors’ prisons, to pay off court-mandated expenses. They worked at Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen and other fast-food chains, and also have been hired out to individuals for work like lawn mowing or home repairs.

AP / Prisoner Sylvester Hameline works at milking equipment in the dairy at the Montana State Prison.

AP / Prisoner Sylvester Hameline works at milking equipment in the dairy at the Montana State Prison.

In Alabama, where prisoners are leased out by companies, AP reporters followed inmate transport vans to poultry plants run by Tyson Foods, which owns brands such as Hillshire Farms, Jimmy Dean and Sara Lee, along with a company that supplies beef, chicken and fish to McDonald’s. The vans also stopped at a chicken processor that’s part of a joint venture with Cargill, which is America’s largest private company. It brought in a record $177 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2023 and supplies conglomerates like PepsiCo.

Hickman’s Family Farms, which pitches itself as the Southwest’s largest egg producer, has employed prisoners for nearly 30 years and supplies many grocery stores, including Costco and Kroger, marketing brands such as Eggland’s Best and Land O’ Lakes. It is the state corrections department’s largest labor contractor, bringing in nearly $35 million in revenue over the past six fiscal years.

During the six-year period the AP examined, surplus raw milk from a Wisconsin prison dairy went to BelGioioso Cheese, which makes Polly-O string cheese and other products that land in grocery stores nationwide like Whole Foods. A California prison provided almonds to Minturn Nut Company, a major producer and exporter. And until 2022, Colorado was raising water buffalo for milk that was sold to giant mozzarella cheesemaker Leprino Foods, which supplies major pizza companies like Domino’s, Pizza Hut and Papa John’s.

Most companies didn’t respond to the AP’s request for comment on their connections to prison labor.

Though Tyson did not respond to questions about direct links to prison farms, it said that its work-release programs are voluntary and that incarcerated workers receive the same pay as their civilian colleagues.

Hickman’s, which has faced a number of lawsuits stemming from inmate injuries, did not respond to emailed questions or phone messages seeking a response.

Cargill acknowledged buying goods from prison farms in Tennessee, Arkansas and Ohio, saying they constituted only a small fraction of the company’s overall volume. It added that “we are now in the process of determining the appropriate remedial action.”

McDonald’s said it would investigate links to any such labor, while Archer Daniels Midland and General Mills, which produces Gold Medal flour, pointed to their policies in place restricting suppliers from using forced labor. Whole Foods responded flatly: “Whole Foods Market does not allow the use of prison labor in products sold at our stores.”

Bunge said it sold all facilities that were sourcing from correction departments in 2021, so they are “no longer part of Bunge’s footprint.”

Dairy Farmers of America, a cooperative that bills itself as the top supplier of raw milk worldwide, said that while it has been buying from correctional facilities, it now only has one “member dairy” at a prison, with most of that milk used inside.

The movement of agricultural goods is complex to track.

A shadow workforce with few protections

The AP sifted through thousands of pages of documents and spoke to more than 80 current or formerly incarcerated people. They found people who were hurt or maimed on the job and interviewed women who were sexually harassed or abused, sometimes by their civilian supervisors or the correctional officers overseeing them.

Though it’s often nearly impossible for these workers to sue, some have, like Frank Dwayne Ellington. In 2017, the 33-year-old was cleaning a machine near the chicken “kill line” in Ashland at Koch Foods when its whirling teeth caught his arm and sucked him inside, crushing his skull and killing him instantly.

During a yearslong legal battle, Koch Foods at first argued Ellington wasn’t technically an employee, and later said his family should be barred from filing for wrongful death because the company had paid his funeral expenses. The case eventually was settled under undisclosed terms. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration fined the company $19,500, saying workers had not been given proper training and that its machines had inadequate safety guards.

Many of the companies buying directly from prisons are violating their own policies against the use of such labor, but it’s completely legal, dating back largely to the need for labor to help rebuild the South’s shattered economy after the Civil War.

Enshrined in the Constitution by the 13th Amendment, slavery and involuntary servitude are banned except as punishment for a crime. That clause is currently being challenged on the federal level, and efforts to remove similar language from state constitutions are expected to reach the ballot in about a dozen states this year.

Corrections officials and other proponents note that not all work is forced and that prison jobs save taxpayers money. For example, in some cases, the food produced is served in prison kitchens or donated to those in need outside. They also say workers are learning skills that can be used when they’re released and given a sense of purpose, which could help ward off repeat offenses. In some places, it allows prisoners to also shave time off their sentences, and the jobs provide a way to repay a debt to society, they say.

While most critics don’t believe all jobs should be eliminated, they say incarcerated people should be paid fairly, treated humanely and that all work should be voluntary. Some note that even when people get specialized training, like firefighting, their criminal records can make it almost impossible to get hired on the outside.

“They are largely uncompensated, they are being forced to work, and it’s unsafe. They also aren’t learning skills that will help them when they are released,” said law professor Andrea Armstrong, an expert on prison labor at Loyola University New Orleans. “It raises the question of why we are still forcing people to work in the fields.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.