The case came to a head on August 23, after Swiss NGO TRIAL International published a press release saying that, according to information recently made public, Nezzar was “on his deathbed”. In the event of his death, “the case will be closed and the victims’ demands will forever remain unanswered, leaving the wounds of the ‘black decade’ open,” says the press release. Just days later, on August 28, the Swiss public prosecutor’s office filed an indictment with the Federal Criminal Court, which is competent to try him under the principle of universal jurisdiction.

The Swiss NGO based its information on an August 12 article on the Atalayar website by Hichem Aboud, an exiled journalist and author of the book La Mafia des généraux (2002), in which he claimed that the former minister was very ill, even dying.

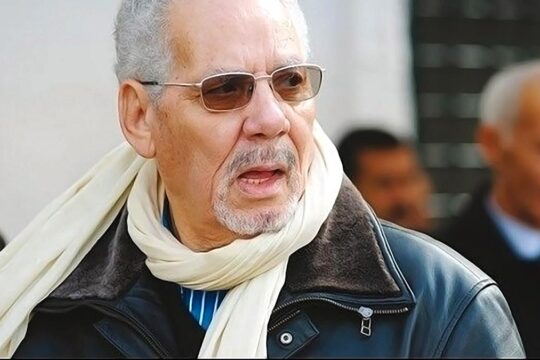

General Nezzar has lived secluded in his home in the heights of Algiers since returning from exile in Spain in December 2020, and no longer sees anyone outside his family circle, according to sources close to him — a seclusion that resembles house arrest. At 85, the man is suffering from a number of illnesses, which are kept secret, but his state of health is not critical, according to the same source. Nezzar is said to be feeling more psychologically than physically depressed after the dismantling of companies run by his eldest son Lotfi, in the wake of measures against the oligarchs around former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who died two years ago. These companies include SLC, the leading provider of WiMax, a high-speed Internet access system. Nezzar is also said to be very affected by statements made against him by his youngest son, Sofiane, who accuses his father of having killed his mother.

Nezzar has not made any statement since his indictment. However, on September 6 he wrote to two Algerian newspapers, Le Soir and El-Khabar, to deny reports that he had received a visit from the Saudi ambassador at his home. “I would like to take this opportunity to welcome the Minister of Foreign Affairs’ statement following the violations committed by the Swiss Criminal Court in the handling of my case,” he wrote at the end of his message. He thus indicated that he was relieved to be under the State’s protection, but that he also knew his room for manoeuvre had been considerably reduced since the disappearance of his protector Bouteflika.

“A revisionist reading by Swiss justice”

His two lawyers in the Swiss proceedings, Caroline Schumacher and Magali Buser, took it upon themselves to respond to the indictment. In a timid and little publicised statement issued on August 28, they denounced a case “marked by repeated violations of the defendant’s right to be heard, in particular the almost systematic refusal of investigative acts requested on his behalf”. His defence argues that “the investigation of the case against him has from the outset been part of an eminently political context. The plaintiffs all claimed to be Islamists, then and now. The General embodies the rejection of the extremist Islamist political project”. But they did not say whether or not he would be prepared to appear in Switzerland.

The day after this press release, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs sought to make public the content of a telephone conversation between the Algerian Minister, Ahmed Attaf, and his Swiss counterpart Ignazio Cassis. The official Algerian agency published extracts of what Attaf had to say during the conversation, without indicating what Cassis said. “The whole world recognises that Algeria was fighting terrorism, with the exception of the Swiss justice system,” said Attaf, deploring a “revisionist reading by the Swiss justice system, of Algeria’s brave and solitary fight against terrorism”. Threatening to break off diplomatic relations with Bern, Attaf expressed the hope that “everything will be done to prevent this affair from dragging relations between Algeria and Switzerland down the path of the undesirable and the irreparable”.

Attaf’s comments were widely reported in the Algerian media. On social networks, opinions are more nuanced: some, as a matter of principle, denounce “any foreign interference” in the affairs of Algerians, even if they do not necessarily support Nezzar; while others believe that the former minister “saved the Republic” by taking the decision to stop by force the 1992 elections, which would otherwise have allowed the Islamists to take power.

There are also those, less vocal, who are delighted with this procedure. Kamel Guemmazi, a former leader of the FIS [Islamic Salvation Front, which would have won the 1992 elections], described Nezzar’s possible appearance in court as a “victory for the victims and families of the disappeared”. “This day has been awaited for 30 years,” he told the London-based Al-Magharibia channel on August 30. “We would have liked this trial to take place in Algeria, but unfortunately, there is no justice in Algeria!”

Algerian political figures, including those considered close to the former defence minister like former Prime Minister Sid-Ahmed Ghozali, have chosen not to speak out on this.

The Rifaat al-Assad example

Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune met his Swiss counterpart Alain Berset on September 18 in New York on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. Although nothing has leaked from this brief exchange, it is highly likely that the Nezzar affair, which has become an issue between the two countries, was central to the discussions.

In a September 4 press release, TRIAL International points out that it is independent of the Swiss government and “in no way speaks on its behalf”. The NGO points out that it does not “in any way defend particular political or religious interests” and “above all defends victims of the most serious crimes, who have an absolute right to obtain justice, regardless of their orientation or convictions”. TRIAL International also points out that the accused does not dispute the legitimacy of the proceedings against him, and that his lawyer stated last year that Nezzar “would appear at his possible trial”.

In conclusion, TRIAL International hopes that Nezzar’s trial “will provide a unique opportunity for the victims of the mass crimes committed during the 1990s in Algeria to obtain a measure of justice and truth”.

To date, Switzerland has not issued an arrest warrant for Nezzar, although in August it unveiled an international arrest warrant for Rifaat Al-Assad, the younger brother of former Syrian president Hafez Al-Assad, for war crimes dating back to 1982. Rifaat Al-Assad is being prosecuted on similar charges to the former Algerian president. The similarities between the two defendants do not end there. Al-Assad, former commander of the Syrian Defence Forces, is accused of having committed massacres during a military operation to regain control of Hama, during an armed uprising led by the Muslim Brotherhood. In 2021, al-Assad returned to Syria after 37 years in exile.

“If Algeria refuses to hand over the accused, will Switzerland turn to the International Court of Justice in The Hague to force Algeria to comply with the Aut dedere, aut judicare [obligation to extradite or prosecute] principle laid down in the International Convention against Torture?” asks lawyer Sofiane Chouiter, president of the Justitia centre for the legal protection of human rights in Algeria. This, she adds, is what Belgium did when Senegal was refusing to hand over former Chadian dictator Hissène Habré or put him on trial.

Recommended reading

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.