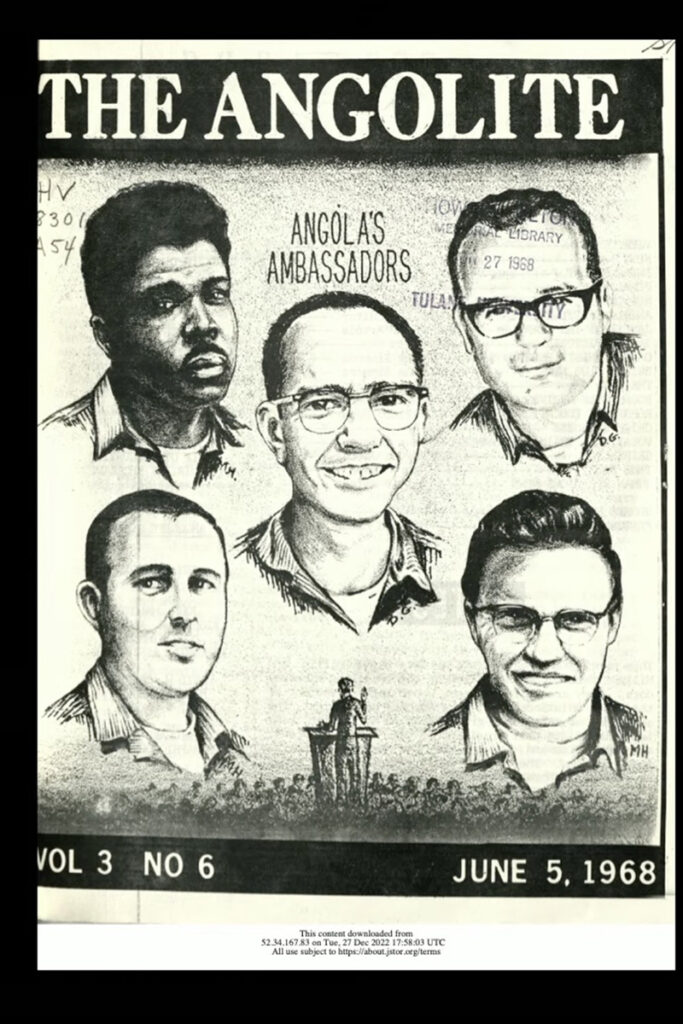

In the 1950s and ‘60s, men incarcerated in Louisiana’s notorious Angola State Penitentiary regularly were allowed to leave the prison under supervision for various reasons – bridge tournaments, Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, speaking engagements at churches and schools. There was even a country western band made up of incarcerated men who played local gigs.

It wasn’t that Louisiana at that time was particularly progressive. Prior to the 1980s, all across the United States, incarcerated people were more likely than today to be granted furloughs or conjugal visits to remain connected to family, friends, and the outside world. And, according to historian Reiko Hillyer, they were more likely to be released before their sentence was up.

“Even the harshest prisons in the country, especially in the Jim Crow South, had robust traditions of clemency, conjugal visits, and furlough, and it’s this permeability that I try to trace its rise and fall in order to try to understand how it is that we’ve engaged in what I’m calling ‘permanent exile,’” said Hillyer, author of A Wall Is Just a Wall: The Permeability of the Prison in the 20th Century United States.

Hillyer was keynote speaker at this year’s conference on college in prison, hosted by the Emerson Prison Initiative (EPI) and InThrive Film Festival March 18 and 19. The conference featured speakers and panelists, including several EPI alums, talking about the value of higher education in prison and the rights of incarcerated people.

On day two, attendees could watch films by and/or about incarcerated or formerly incarcerated people, including Holding Up the Sky by former affiliated faculty member Bob Nesson, and It Starts with Us, a partnership with We Are Better Together and Emerson College students.

States and prison systems through most of the 20th century tended to grant those incarcerated more freedom and contact with the outside world, not despite, but in many cases, because of their conservative ideologies, Hillyer said.

Clemency sometimes was seen as a way to reduce prison costs. Conjugal visits were introduced by then-California Gov. Ronald Reagan as an antidote to “situational homosexuality,” and Jim Crow prison officials thought weekend visits from wives and girlfriends led to harder workers come Monday. Furloughs were considered by many a commonsense way to re-acclimate people to society prior to release.

But whatever the politicians’ motivations, these policies resulted in an incarcerated population that was less isolated, better trusted, and not as frequently written-off than that of today.

“Prisoners’ withdrawal from free society was understood to be temporary, and their visits outside nourished the connective tissue that would help secure their eventual reintegration into the body politic,” said Hillyer, reading from her book. “By interacting with the public, incarcerated people could develop a sense of dignity beyond the reductive labels imposed by the criminal justice system, and by contributing to society through music, lectures, or charity work, they could counter the public’s preconceived ideas about convicts.”

In the 1980s and ‘90s, national attitudes shifted and Republicans and Democrats alike got “tough on crime.” Mandatory minimum sentences for even relatively minor drug offenses filled prisons and necessitated building new ones. Conjugal visits were discarded in favor of brief encounters behind plexiglass. And furloughs, previously given based on a person’s conduct in prison, came to be restricted based on a person’s original crime, or were banned outright.

“Progress does not happen in a straight line, and we need to understand how the lived experience can inform us of the devastating consequences of these kinds of policy changes,” Hillyer said.

Following Hillyer’s talk, EPI alum David Baxter ’22 talked about his journey through and out of the criminal justice system, and how education provided him with purpose, vision, and choice. The presentation doubled as proof of concept both for EPI and Motivational Dreamers, the public speaking and consulting company Baxter founded.

“I’m living proof … that sometimes the system doesn’t have the final say, and that college behind the wall … is not simply about handing out degrees, it’s about reclaiming stolen futures,” Baxter said.

Prior to his incarceration, Baxter said, he was a college student on the outside. But once he began serving his sentence, he began to feel that education had slipped out of his grasp. Until he applied and was accepted to EPI.

“This time, I understood the value, so this time it was personal, because I wasn’t doing it just for me. I was doing it for my daughter. I was doing it for my mother. So when I sat in that classroom, I wasn’t just a student, I was a man on a mission,” he said.

Education is about more than knowledge, Baxter said, it also means liberation.

“It’s about ensuring you have the capability to build a future far beyond the one that was handed to you. Yet so far, too many are still being denied power because we have a system that is still operating how it was designed – to keep them locked up and locked away from opportunity.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.