Marble busts or portraits made before the age of photography are often viewed as unreliable images, either flattering their subjects or showing somewhat stylised artistic impressions of them. So, when historians captured the under-eye bags, golden ringlets and blotchy, sallow skin of Bonnie Prince Charlie in a 3D reconstruction, it brought to life this historical figure in a new way. Here are some other famous reconstructions:

Maximilien de Robespierre

Maximilien de Robespierre, the French revolutionary and architect of la Grande Terreur, lost his head to the guillotine in 1794. More than 200 years later, leading historical forensic scientists were able to retrospectively diagnose him with the crippling auto-immune disorder sarcoidosis after reconstructing his face. This, they concluded, suggested Robespierre was likely already on his last legs when he was executed.

Using contemporary portraits, and examining his death mask made by the waxwork creator Madame Tussaud, as well as studying witness accounts of the time, experts were able to reconstruct Robespierre’s pockmarked face.

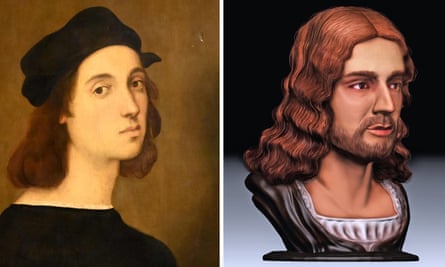

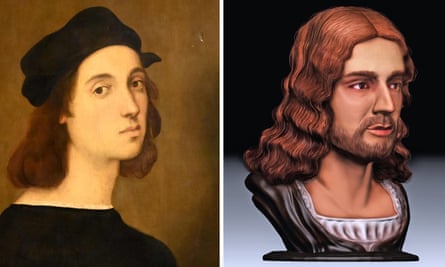

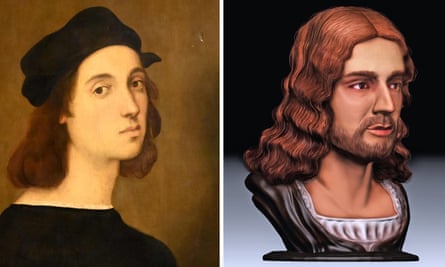

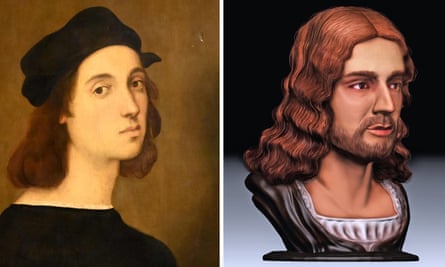

Raphael

In 2020, Italian art experts created a 3D reconstruction of the face of the Renaissance artist Raphael, which they said proved he was buried at the Pantheon in Rome.

Raffaello Sanzio died in Rome in 1520 at the age of 37, eight days after contracting a fever. A plaster cast of his skull that was made after his body was exhumed in 1833 was used to create a realistic model of the artist, along with self-portraits and portraits painted by his contemporaries.

Burke and Hare

A morbid pair of plaster masks depicting two of Scotland’s most infamous murderers were discovered among a number of macabre artefacts, including a hangman’s noose, languishing in the store cupboard of a former prison in 2009.

The reconstructions of the notorious body snatchers Burke and Hare were found at Inveraray jail in Argyll. The Irish labourers sold bodies that were later dissected by the anatomist Robert Knox, at Surgeon’s Square in Edinburgh, but unlike grave diggers who would exhume the bodies, the pair found it easier to kill their victims.

It is still a mystery how the masks got there as neither of the murderers was ever held at Inveraray, nor was anyone ever hanged inside the prison.

Robert the Bruce

Robert the Bruce, the Scottish king who led the Scots to victory against the English at Bannockburn in 1314, was brought to life almost 700 years after his death by facial reconstruction experts at Liverpool John Moores University.

The 3D digital images show a man with a heavy-set face and large, broad features. The reconstructions are based on a cast held at the Hunterian museum of Robert the Bruce’s skull, which historians believe was recovered along with his skeleton in 1818-19 from Dunfermline Abbey and then reinterred. Using the skull cast, they were able to accurately establish the muscle formation from the positions of the skull bones, which helped determine the shape and structure of his face.

There are two versions of the king: one that matches historians prediction that he had a powerful physique, and the other depicting him with leprosy. A disfigured upper jaw and nose led experts to conclude he had leprosy, so another set of digital images portray an older, more worn and marked face carrying the scars of the disease.

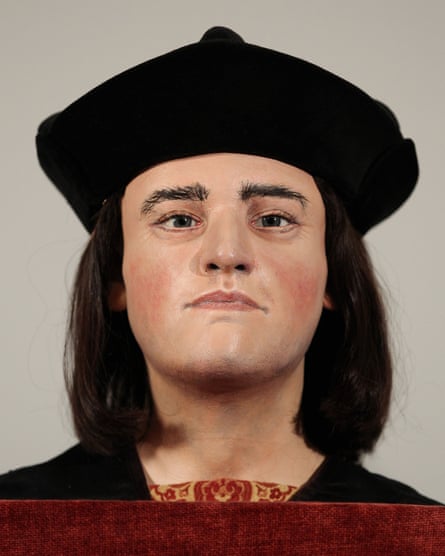

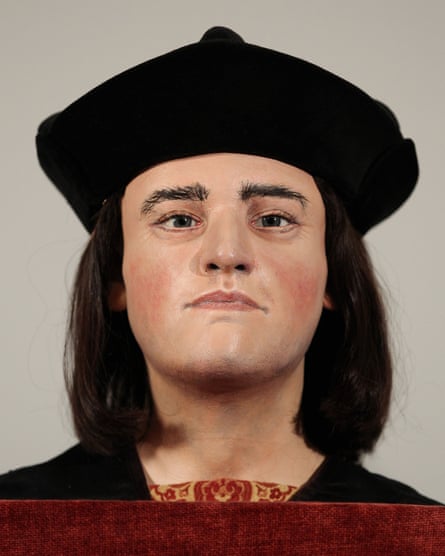

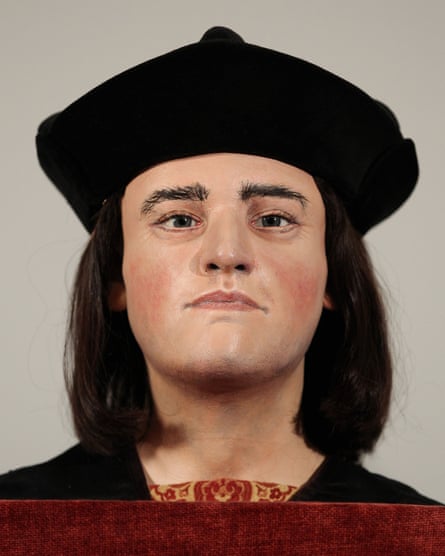

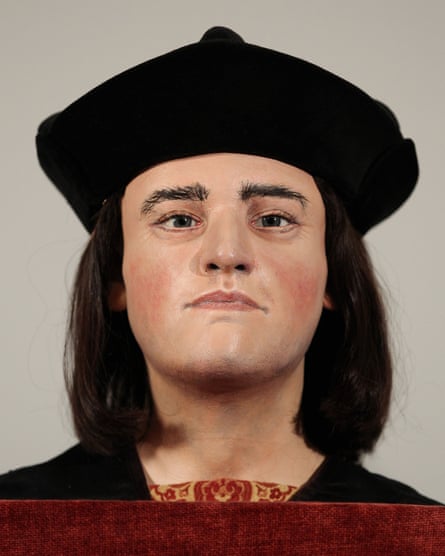

Richard III

When the body of Richard III was discovered by archaeologists in a Leicester car park, a facial reconstruction of the 15th-century king was created. Based on portraits, his skull and his living descendant, Michael Ibsen, who posed beside the model, the reconstruction shows a man with long, brown hair and dark, bushy eyebrows.

The monarch was only 32 when he died on the Bosworth battlefield on 22 August 1485, but the reconstructed face appears much younger. The face was reconstructed from detailed scans of the skull by Caroline Wilkinson, professor of craniofacial identification at Dundee University. Janice Aitken, of the university’s art college, then added the fine details like his hair, eye colour and skin colour and texture using contemporary descriptions and images of 21st century men who spend a lot of time outdoors.

Mary, Queen of Scots

The face of Mary, Queen of Scots was recreated in 3D in 2013 by the same team of experts from the University of Dundee. The depiction reveals just how strange 16th-century portraits look if we see them as real faces.

Wilkinso n created a head-and-neck model using portraits of Mary before and after her time in Scotland, where there are no known portraits of her. Wilkinson used 3D modelling software and craniofacial templates to create an authentic depiction. Digital artist Aitken then sculpted Mary’s clothing and hair, adding textures on her skin to make the likeness as realistic as possible.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.