Photo via Lake County Sheriff’s Office / Facebook

People incarcerated at Lake County Jail and Detention Center fill sandbags ahead of Hurricane Idalia. (Aug. 29, 2023)

As Floridians prepared for Hurricane Idalia to make landfall on the upper central coast earlier this week, several counties deployed unpaid prison labor, as they have in the past, to fill the sandbags used to prevent flood damage.

At least four counties — including Lake County, Polk County, Taylor County and Flagler County — relied on incarcerated people from local correctional facilities to fill sandbags this year.

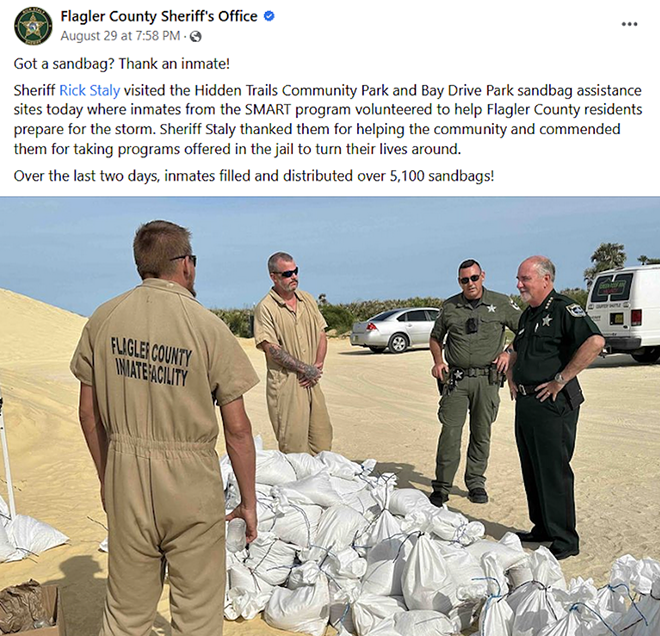

“Got a sandbag? Thank an inmate!” the Flagler County Sheriff’s Office, on Florida’s East Coast near Daytona Beach, shared in a Facebook post a day before Idalia reached Florida as a Category 3 hurricane on the state’s West Coast.

Incarcerated people, a largely invisible workforce who lack basic labor protections, are regularly enlisted to help contain wildfires in states like California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Georgia, and Oregon. They’re also deployed to pick up tree limbs, do road cleanup, and perform other storm preparation and recovery work.

Just like any other first responder, they face the risk of injury, even death out on the front lines, all the while earning less than one dollar per hour on average in most parts of the U.S. In some states, including Florida, incarcerated workers are paid nothing for their labor, or little more than pennies.

Unlike government employees, such as city or county staff enlisted to help prepare communities for natural disasters, most incarcerated labor in Florida is unpaid — as it is in Texas and a handful of other Southern states.

We had a word for that once: slavery. Now? It’s a little more complicated.

The legality of unpaid incarcerated labor (described by some as exploitation and “modern–day slavery”) is tied in part to the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

As the Miami New Times noted following Hurricane Irma in 2017, “inmate work crews” have a long, unsurprisingly racist history in Florida, dating back to at least 1868, when the state’s first penitentiary opened.

The state legislature at the time determined that free prison labor would sufficiently help “offset” the facility’s expenses.

Today, government agencies in Florida that oversee work assignments for incarcerated people generally frame those who do things like filling sandbags ahead of storms (a convenience that could be particularly helpful for the elderly or people with disabilities) as “volunteers.”

“The inmates are extremely grateful to have an opportunity to help our community prepare as they have families here as well,”Brevard County sheriff Wayne Ivey gushed in 2019, as Florida’s Space Coast, east of Orlando, prepared for Hurricane Dorian.

This week, the Flagler County sheriff also thanked those who “volunteered” to fill sandbags ahead of Idalia.

“Over the last two days, inmates filled and distributed over 5,100 sandbags!” the sheriff’s office shared proudly on social media.

Commenters on the post, seemingly fine with this arrangement, also shared praise.

“A double win — citizens in need get help and the inmates get to feel the pride of being needed and helping others,” one person wrote. “Thanks to the inmates who volunteered!” another added.

It’s not the first time Flagler County’s deployed its incarcerated population for storm readiness.

Photo via Lake County Sheriff’s Office / Facebook

Flagler County Sheriff Rick Staley thanks unpaid laborers from the county jail for filling sandbags ahead of Hurricane Idalia. (Aug. 29, 2023)

Ahead of Hurricane Irma in 2017, the FCSO announced what it dubbed “Operation Sandbag,” contrasting its sandbag pickup location with another location that offered self-service.

“Let the inmates do the labor for you,” the sheriff’s office argued.

This year, ahead of Idalia’s arrival, the Lake County Sheriff’s Office, east of Orange County, also recruited incarcerated people to fill sandbags for county residents, who faced a tropical storm warning and were not expected to see a direct hit.

A spokesperson for the LCSO, reached after several, unreturned calls to their office, confirmed that their incarcerated “volunteers” spent eight hours filling sandbags for local residents on Tuesday, unpaid.

“The inmates do not receive any monetary benefits for their duties,” the spokesperson told Orlando Weekly over email. “However, they may receive added privileges, time toward their sentence, and the ability to spend additional time working outside of the jail facility.

There is a “classification” process. Only people who are convicted of a crime (not just booked into the detention center) are chosen for the “work crew.” And people who have been convicted of violent or sexual charges are not eligible.

Using incarcerated labor to perform this work is “cost effective for taxpayers,” the spokesperson explained, “and can also allow inmates to learn a new skill that could help them find gainful employment once they are released from the jail.”

Selling the ‘benefits’ of unpaid prison labor to the public

Those who defend the practice of unpaid prison labor argue that working while incarcerated can help to reduce recidivism, promote skill development, and offer personal fulfillment for those who are convicted of crimes.

But unemployment among formerly incarcerated people is notoriously high, and it’s not because they don’t want to work. It’s also not clear that unpaid labor during incarceration actually helps increase a person’s chance of finding gainful employment.

A person’s criminal history, for instance, may disqualify them from jobs that they performed while incarcerated, regardless of a possibly improved skill set. Formerly incarcerated people, desperate to find work post-release, may also be at greater risk for exploitation, or may face a limited employment pool of jobs that are low-wage, unstable, and offer zero to little mobility, according to the Prison Policy Institute.

But, it’s true that this arrangement in the corrections system allows for savings on labor costs. Florida’s minimum wage is $11 per hour, compared to $0 for the majority of prison work (a small fraction of prison jobs in Florida pay between 20 cents and 95 cents per hour, according to data collected from the ACLU).

These cost savings are not lost on the state Department of Corrections, which maintains contracts with local and state government agencies, including the Department of Transportation.

As of 2019, the Florida Department of Corrections valued incarcerated laborers working on state “community work squads” and road crews at $147.5 million over a five-year period, according to the Florida Times-Union, which clarified that the real value is “likely double or triple that estimate.”

“There’s no way we can take care of our facilities, our roads, our ditches, if we didn’t have inmate labor,” Warren Yeager, a former Gulf County commissioner told the Florida Times-Union in 2019.

Managing correctional facilities — where incarcerated people may also be directed to do kitchen work, work in laundry or perform janitorial tasks — is also expensive.

“Incarcerated workers’ labor partially offsets the staggering costs of our country’s bloated prison system,” the ACLU wrote in a 2022 report on prison labor.

Leon County, which had braced itself for a particularly rough hit from Idalia on Wednesday, saves roughly $195,200 annually by using incarcerated labor instead of hiring permanent full-time staff, according to Tallahassee Reports.

Incarcerated workers are exempted from basic labor protections — such as the right to be paid minimum wage, receive benefits or overtime pay — and can face consequences for refusing work, including disciplinary confinement and losing time earned off their sentences.

Court decisions have also determined they don’t have the right to unionize, although that hasn’t stopped them from forming unions anyway, organizing with groups like the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee.

The IWOC, a prison-led branch of the radical Industrial Workers of America, first formed in 2014 and is known for sponsoring a series of prison strikes in 2018 over wages and other prison conditions, in step with the Campaign to Fight Toxic Prisons and Jailhouse Lawyers Speak.

Thousands of prisoners reportedly participated. But, as The New Yorker reported at the time, an accurate count of participation was difficult to determine “in part because some state-prison officials refused to confirm that a strike had occurred.”

Strikes have also been organized at other points throughout the past decade, and in decades past.

The issue of unpaid prison labor in Florida hasn’t gone completely unnoticed by those with the power to address it. Some Democratic state lawmakers in Florida, for instance, previously sought to ban unpaid prison labor as recently as 2022, but those efforts haven’t gone anywhere, and the issue was not pursued this past legislative session.

Meanwhile, advocates for Florida’s incarcerated population are also fighting for other basic rights for those imprisoned, including heat protection.

Most Florida prisons lack AC, which poses serious health and safety risks for everyone inside: those imprisoned as well as corrections staff.

Of course, only one of those groups can’t leave.

Hurricane season in Florida has yet to reach its peak for 2023. And it’s likely that incarcerated people will, again, be deployed to help communities prepare and recover from upcoming storms.

Local agencies in other parts of Florida, including Dixie, Osceola,Pasco, and Manatee counties — have also used prison labor for storm cleanup in the past. The Orange County Department of Corrections did not respond to Orlando Weekly’s request for comment on whether they have or plan to direct incarcerated people to help with storm recovery.

At least one government agency — the Lake County Sheriff’s Office — confirmed they will “absolutely” be utilizing incarcerated labor for storm preparation and recovery in the months to come, “provided conditions are safe enough.”

This story was first published at our sister publication Orlando Weekly.

Subscribe to Creative Loafing newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.