Roles were flipped and those who work in the justice system were suddenly on the “other side of the law” as they participated in a reentry simulation at the Pennsylvania College of Technology recently.

“Eye opening” was the phrase used to best describe the experience as the participants encountered the difficulties ex-prisoners face as they try to navigate life after jail.

The event was coordinated by Craig A. Miller, professor of history/political science at Penn College and a member of the Lycoming County Criminal Justice Advisory Board, and Penny Sines, parole manager with the state Department of Corrections’ Bureau of Offender Reentry.

Those participating as parolees included representatives from various Lycoming County offices and agencies such as Adult Probation, Juvenile Probation, GEO Reentry Services, the Lycoming County Prison, and corrections officers and officials.

The participants are given a chance to “see what the world looks like from their clients’ perspective,” Miller said.

“They might have only ever been on this side and they haven’t walked in those people’s shoes,” said Sines.

The state has reentry offices in all of the State Correctional Institutions.

“We try to educate everybody because if they don’t have all the stuff in place before they get out, they’re gonna need that to keep moving forward. Because if they don’t, they’re gonna fail, and they’re gonna keep coming back to prison,” Sines said.

“The mindset of being on parole has definitely changed. We don’t just bring them back to prison, we try to keep them moving forward,” Sines said.

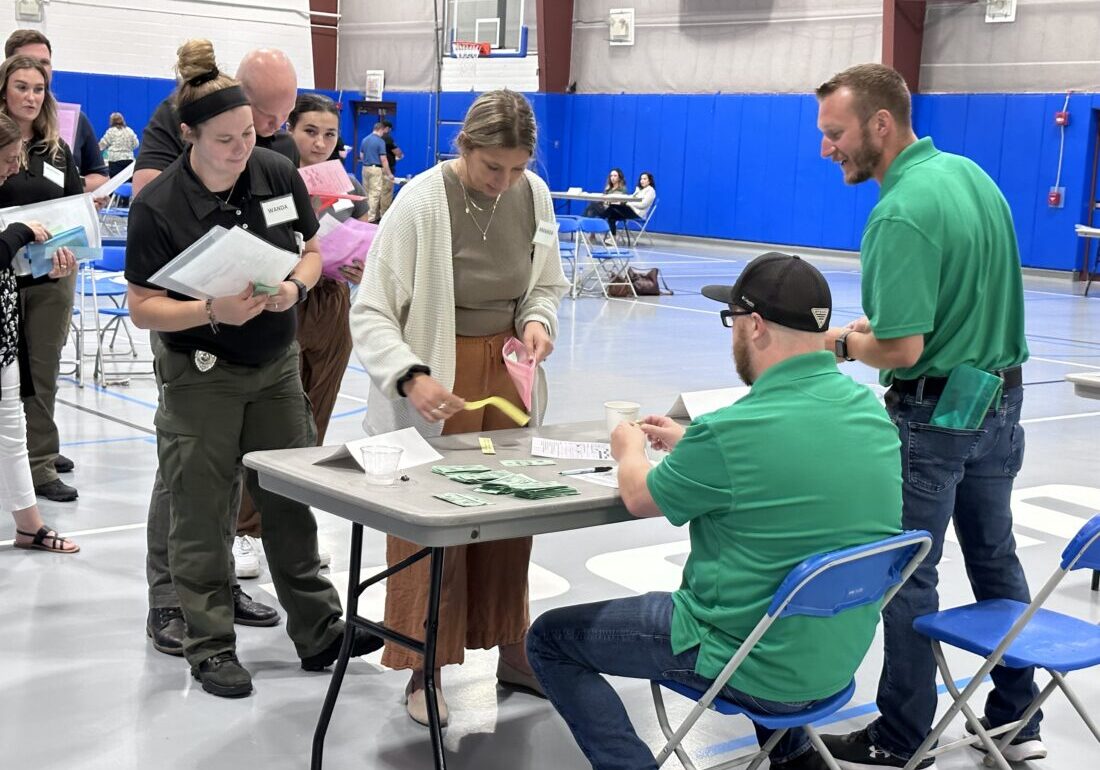

Tables had been set up around the perimeter of the Field House gym at Penn College where the simulation occurred. Each table represented some aspect of a challenge a parolee might experience when leaving prison, such as obtaining a job, funding transportation, seeking counseling and medical care, or getting money by visiting the pawn shop. There was also an area designated as a homeless shelter for those who failed to pay rent for the week and of course there was an area for those who did something they should not have and had to be sent back to jail.

The simulation begins with each person receiving a packet containing their parolee name and their life card, which lists goals that they have to do each week. A week consists of 15 minutes. During that time they had to do such things as obtain an identification card if there wasn’t one in their packet.

They were reminded by Sines that you have to have an ID for everything, so when the first “week” began, the line at the ID table was the longest.

“If you don’t have IDs, it’ll be marked with a copy of your life card. You have to have all three IDs to do anything, so if you go to a table and you don’t have your ID’s, they’re going to turn you away,” she said.

Transportation is another issue often faced by people coming out of prison because they may not have a driver’s license or live where they can get transportation. Mass transit is a viable alternative, but you need tokens. Tokens at the simulation could be purchased for a dollar

and could be purchased five at a time. They could receive rental assistance one time and can earn money by donating plasma twice.

At the end of each 15-minute session, the cards are checked to see what has been completed. Sometimes there are consequences if someone missed an appointment with their parole officer or they didn’t pay rent, Sines said she tells participants.

One thing they’re not allowed to do is give up and say that they’re just going to go to jail and sit there until the simulation is over.

For two hours the participants tried to figure out how to manage the “outside world.” In the end, some went to jail and some still were homeless.

“We got a lot of, ‘Wow, this was really hard. No one helped us,’” Sines said.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.