Ethiopia’s Special Prosecutor’s Office needs an international cooperation unit

To effectively deliver justice for international crimes, an independent international cooperation unit is essential.

Ethiopia is drafting transitional justice laws to address past and ongoing abuses through criminal accountability, truth-seeking, reparations and institutional reform.

One of the draft laws establishes a Special Prosecutor’s Office (SPO, or what might be called a Transitional Justice Prosecutor’s Office) to investigate and prosecute those most responsible for core international crimes and other grave offences such as rape. In Ethiopia’s draft law, international crimes include genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, torture and enforced disappearances.

The proposed SPO will be required to search for, identify, and prosecute alleged perpetrators outside Ethiopia’s jurisdiction or foreign nationals implicated in crimes under its authority. Going after fugitive offenders is a complex task. Identifying their whereabouts may not always be possible using conventional means. In those cases, the draft law allows the SPO to incentivise informants to provide crucial intelligence.

Equally challenging is securing extradition and accountability for these perpetrators. When extradition requests are denied – often due to the numerous legal grounds for refusal invoked by the requested state – the SPO should try to persuade and support third-party states to prosecute offenders under universal jurisdiction or other applicable legal doctrines. This requires sustained collaboration with international stakeholders and foreign countries.

Recognising these difficulties, states adopted an international cooperation treaty in 2024 – the Ljubljana-The Hague Convention. The treaty is designed to enhance cross-border collaboration in investigating and prosecuting crimes akin to those that Ethiopia’s SPO will address.

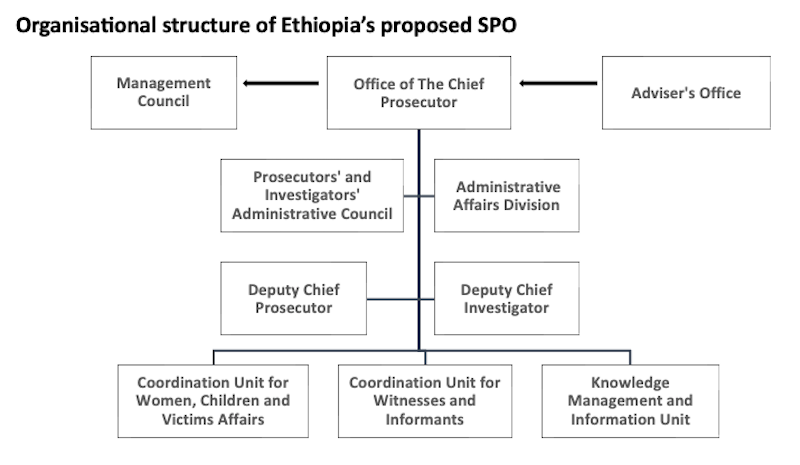

Yet, while it is equipped with some specialised divisions, the proposed SPO lacks a key department to effectively discharge its mandate: a dedicated international cooperation unit.

Such a unit, equipped with adequate resources, technical expertise, vetted experts and a strong institutional mandate, is essential for at least three reasons: the Eritrean dimension of transitional justice, Ethiopia’s history of dealing with fugitive offenders, and the SPO’s independence.

First, unlike the post-1991 prosecutions of Dergue-era crimes, which targeted solely Ethiopian nationals, the new SPO is expected to investigate non-Ethiopian perpetrators, particularly Eritreans accused of atrocities committed during the Tigray war.

Eritrea’s government has historically resisted cooperation in matters of accountability. During the post-1991 trials, it refused to share military communiqués and other evidence with Ethiopian prosecutors, even when requests did not involve prosecuting Eritrean nationals. This lack of cooperation, said the post-1991 SPO report, hindered Ethiopia’s efforts to prosecute war crimes.

Given this precedent, having no dedicated international cooperation mechanism risks signalling a lack of commitment to holding Eritrean offenders accountable. An international cooperation unit could help facilitate diplomatic engagements, secure evidence, and advocate for Eritrean perpetrators to be prosecuted in Ethiopia, Eritrea, or a third-party jurisdiction.

Second, Ethiopia’s past challenges with extradition and transnational justice highlight the need for a dedicated international cooperation division in the new SPO. The post-1991 Dergue trials led to many in absentia prosecutions due to the high number of fugitives. A total of 2 188 of 5 119 defendants were tried in absentia. Twenty of the 73 high-ranking Dergue officials prosecuted in ‘Mengistu et al.’ were absent from the proceedings, including Mengistu Haile Mariam himself.

The Dergue trials normalised in absentia prosecutions, not because Ethiopian law encouraged them, but because international cooperation failed. Ethiopian criminal law usually treats these as a measure of last resort. It imposes a duty on the prosecuting authority to search for fugitives and request extradition before prosecuting in their absence.

A former member of the post-1991 SPO told ISS Today that the lack of a dedicated international cooperation unit meant prosecutors could not actively secure extradition for any high-profile fugitives. In the post-1991 SPO’s history, only Melaku Teferra was handed over by Djibouti from its consulate in Ethiopia.

Moreover, the post-1991 SPO failed to prosecute Ethiopian fugitives in other countries. America’s trials of former Dergue members like Kelbessa Negewo (under the Alien Tort Claims Act), and Mergia Negussie Habteyes and Mezemr Abebe Belayneh (for immigration fraud), were not thanks to Ethiopia’s efforts. Similarly, the war crimes conviction of Eshetu Alemu in the Netherlands occurred after the post-1991 SPO closed down in 2010 on completion of its mandate.

Research revealed the ineffectiveness of the post-1991 SPO process in tracking fugitives, even in Ethiopia. Some individuals convicted in absentia in the Dergue trials later resurfaced, claiming they were never informed of the proceedings against them. Some died before their trials even began.

Experience with the Dergue trials also shows that Ethiopia’s limited extradition requests have been denied due to a lack of bilateral or multilateral treaties governing such cooperation. The SPO at the time made no significant effort to address this deficiency.

Ethiopia still lacks extradition treaties with several key jurisdictions and has not signed the Ljubljana-The Hague Convention. An independent international cooperation unit could advocate for legal reforms and close these gaps.

Furthermore, compared to its predecessor, the new SPO would likely face even more fugitive offenders. The protracted nature of the transitional justice process – already spanning over six years – might have given alleged perpetrators time to flee the country.

Given that the jurisdiction of the proposed new SPO encompasses crimes committed over more than three decades – twice the temporal scope of the post-1991 SPO – the number of implicated individuals residing abroad is likely much higher.

Third, while Ethiopia’s Justice Ministry has an international cooperation unit, it isn’t structured to meet the new SPO’s demands. The draft law makes the SPO accountable to Parliament to ensure its independence. But the ministry’s regular international cooperation department lacks such independence, remaining accountable to the executive branch. If the regular cooperation unit handles SPO matters, that would risk undermining the SPO’s independence.

Not having a dedicated international cooperation unit in the new SPO represents a critical gap in Ethiopia’s proposed transitional justice framework, and could undermine its credibility.

Establishing an independent, specialised unit would improve the delivery of justice for international crime, and have a lasting impact on Ethiopia’s judicial system. It would transfer knowledge and expertise to the regular prosecution department, extending its benefits beyond its mandate and term.

Exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles have been given to Daily Maverick in South Africa and Premium Times in Nigeria. For media based outside South Africa and Nigeria that want to re-publish articles, or for queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.