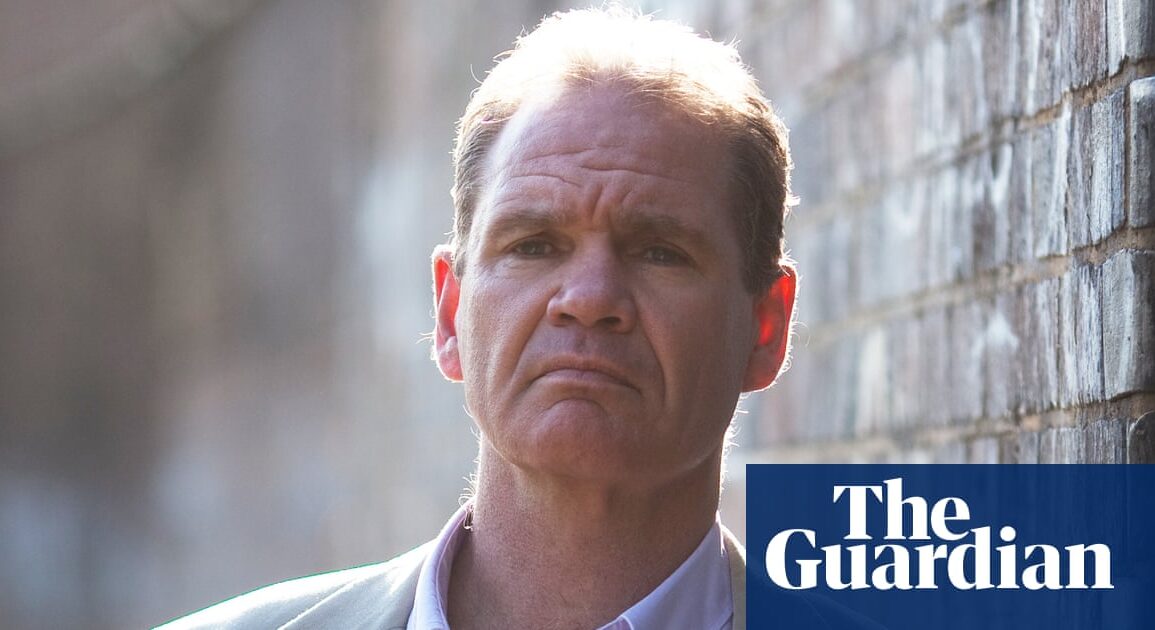

Erwin James, the writer of an influential Guardian column about life in prison who would go on to be a leading voice on criminal justice, has died.

James, real name Erwin James Monahan, was convicted of murder in 1984 and served 20 years in prison.

He wrote the Guardian column, A Life Inside, from 2000 until his release in 2004, and continued to write extensively for the newspaper afterwards, offering a glimpse of the reality of life behind bars and the challenge faced by those trying to build a rehabilitated life after it.

The first such column of its kind in the UK, it won him unlikely admirers including the former Conservative minister Jonathan Aitken, himself a convicted criminal, and was credited with inspiring a generation of prison reform campaigners.

He was the author of three books, including a memoir, Redeemable: A Memoir of Darkness and Hope, published in 2016, which detailed his troubled childhood and life in the Foreign Legion while on the run from his crimes, as well as his years in prison.

That year he became the editor of Inside Time, the prisons newspaper, which he had described as his “dream job”, continuing in the role until 2023.

James died suddenly at his home in Devon on 19 January, leaving his wife, Margaret, his sister and two daughters. He was 66.

The Prisons Reform Trust, of which he was a former trustee, described him as “a man of deep intelligence, humility and warmth”.

Ian Katz, now the chief content officer at Channel 4, who as Guardian features editor first commissioned James to write for G2, said: “Jim was an acute observer of people and gifted writer who offered us a rare, humane – and frequently hilarious – insight into life inside the prison system.

“He was also something still rarer – physical embodiment of the possibility that even people who have done the most terrible things can turn their lives around in prison and earn a second chance at life.

“Jim put his second chance to extraordinary account – he challenged our assumptions not just about the prison system but about those who commit the most heinous crimes. He was generous, open, funny, vulnerable and will be greatly missed.”

Writing on X, Alan Rusbridger, the former Guardian editor, called his death “a big loss”, saying: “Erwin James wrote a really remarkable column from prison for the Guardian, full of humanity and insights into life inside, and the purpose of prison – in theory and in practice.”

The prisons campaigner Mark Leech said James was a “hugely talented man”, adding: “He did so much to highlight the plight of prisoners and will be greatly missed.”

John Roberts, the publisher and director of Inside Time, said: “We shall be forever grateful to Erwin for his contribution to the success of Inside Time during his time as editor, and he will be missed.”

In 1984, aged 28, James was sentenced to life alongside another man for murdering Greville Hallam, a theatrical agent, and Angus Cochrane, a solicitor. Hallam, 48, was robbed and strangled in his north London home in September 1982. Cochrane, 29, died after being mugged in the West End three months later.

James wrote in 2009: “I can only express my heartfelt sorrow for what I did. My behaviour was unforgivable and I seek no forgiveness now.”

In prison, where James would later write that inmates “exist on dreams, nightmares and fantasies”, he found that reading and writing were crucial to his survival.

“Locked in my cell for 23 hours a day with few apparent skills or abilities, and almost insurmountable failings to overcome – my prospects were bleak,” he wrote. So he devoured paperbacks from the prison library, studied for an Open University degree and began to write.

“I involved myself in writing groups, helped to publish prison magazines, wrote letters to newspapers. While my role as camp scribe flourished, I indulged in another fantasy. If my life had been different, perhaps I could have been a writer, maybe a journalist,” he wrote.

His first article was published in the Independent in 1994. Then, in 1998, he began speaking to the Guardian, eventually being commissioned to write what became A Life Inside in 2000.

After his release in 2004, he worked as a writer and became a trustee of the Prison Reform Trust and the Alternatives to Violence Project. He was a consultant to Iain Duncan Smith MP on prisoner rehabilitation and a commissioner on the panel of the Westminster Commission on Miscarriages of Justice, as well as a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) and patron of several charities.

On becoming a full-time writer, James grappled with the knotty issues of what it meant to achieve success after his crimes.

“Words are insufficient to express how sorry I am for the pain I have caused – and I know that my ‘success’ is still painful for at least some of those people,” he wrote in 2015. “When I went to prison for life I was a damaged, ignorant brute.”

He said learning and knowledge had helped open him up to an alternative future, furnishing him with a sincere belief in the power of rehabilitation and a second chance for people formerly incarcerated.

“Hand on heart, I know that most of the people I served alongside had the desire to change and live crime-free lives,” James wrote.

“For some, the problems and issues they faced were so deep-rooted that progress was unlikely. But in the right environment and with the right attitude from government and society in general, rehabilitation was achievable for the majority.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.