When Marisol Garcia went back to prison for a probation violation in 2015, she found that education made her feel like she lived beyond bars.

“To be able to write, to be able to read, you know, ‘Moby-Dick’ or Cervantes, or Shakespeare, you’re able to go into a whole other world that’s no longer between the four walls,” she said.

She obtained vocational training, then began her associate degree while incarcerated. She was exposed to prison education programs from Trinity College, Quinnipiac University and Wesleyan University. After leaving prison, she completed a bachelor’s degree, earned a master’s degree and enrolled in law school.

But fewer and fewer people are accessing the kind of education Garcia received while incarcerated.

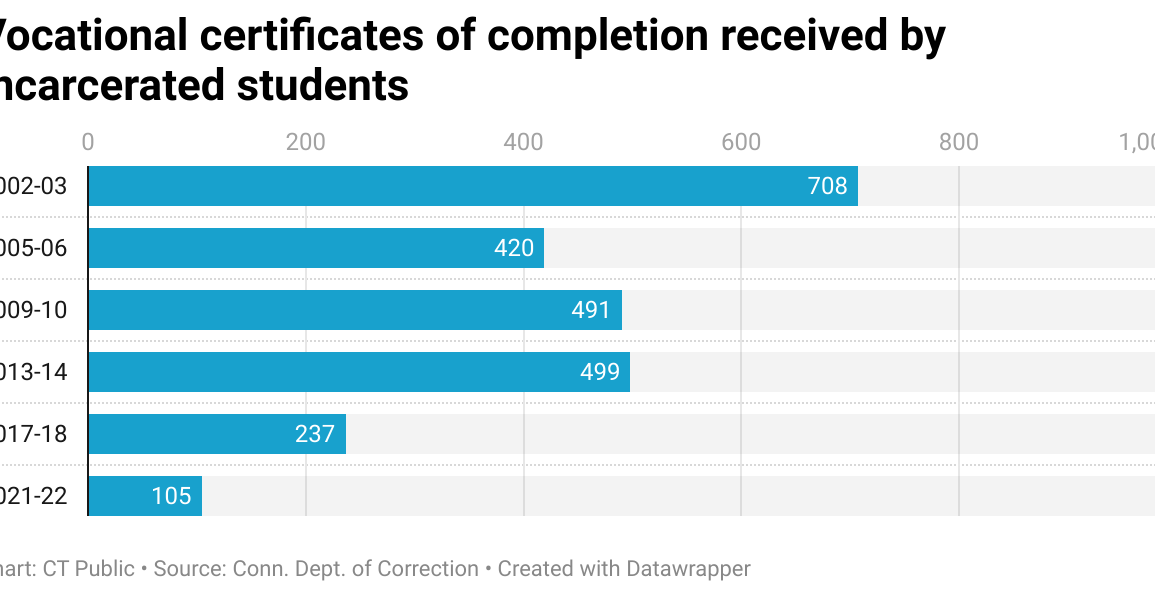

A review by Connecticut Public found educational attainment in the state prison system has dropped sharply in recent years. Fewer people are getting high school diplomas, finishing vocational programs or enrolling in classes offered through the prison school system, known as Unified School District #1.

Even for Garcia, who was motivated to learn, there were barriers, including a months-long wait to start vocational training.

Local colleges also provide programs for people who are incarcerated, but many are competitive, and require multiple rounds of interviews and essays to enroll, Garcia said.

Declines in educational attainment are concerning because many people in prison are already behind in schooling, said Matthew Denney, a postdoctoral fellow at SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins.

In Connecticut, half of people in prison don’t have a high school diploma, and many enter school programs with skills around a fourth or fifth grade level, according to information published by corrections officials.

Access to learning helps bridge that gap, Denney said.

“It really changes outcomes for people who are coming out of prison because of the ways that socioeconomic opportunities are strongly connected to outcomes coming out of prison,” he said.

Teacher shortage, pandemic disruptions

The Department of Correction (DOC) operates its own school district, and offers everything from high school classes to English language instruction and vocational training.

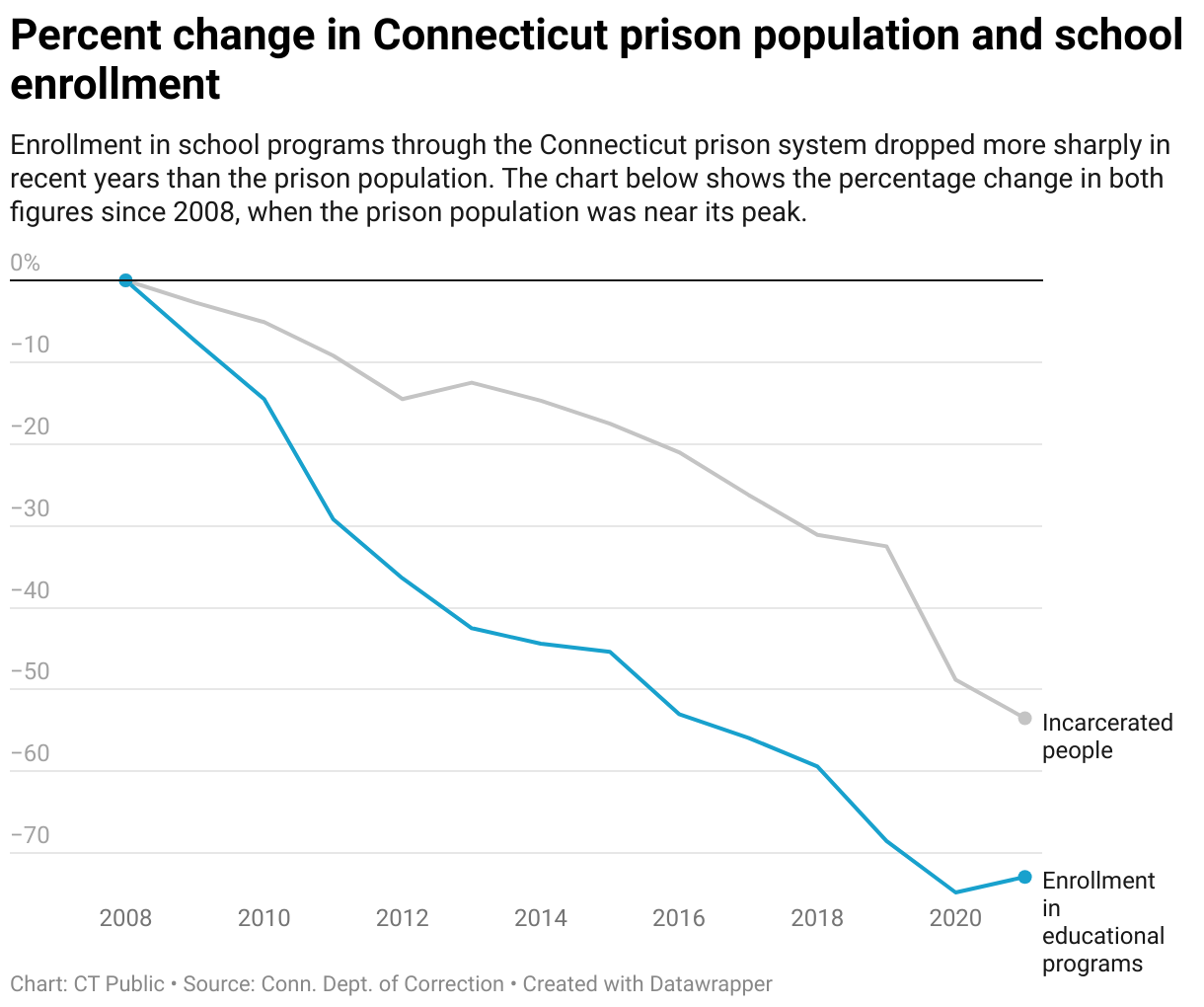

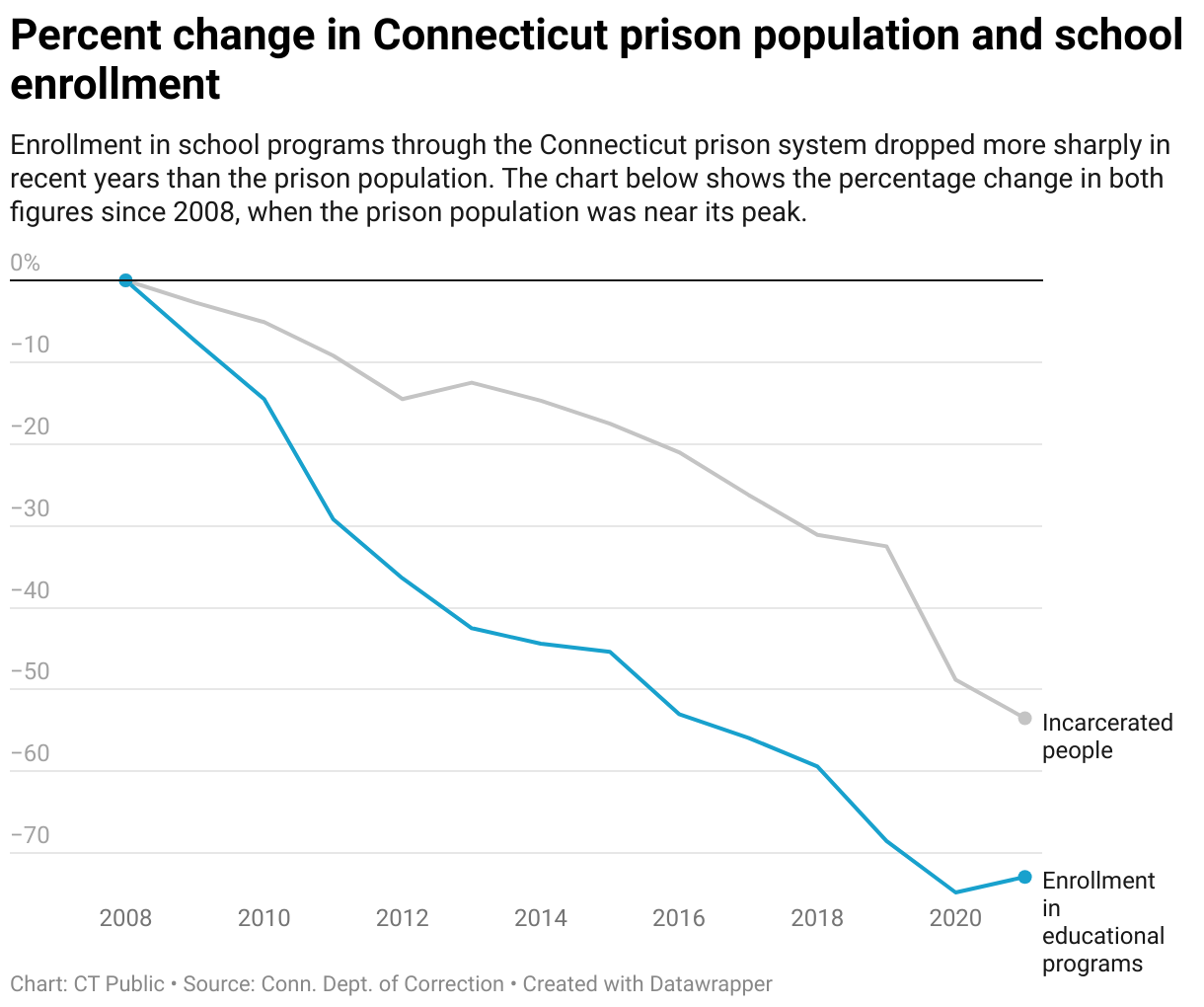

But the number of incarcerated people enrolled in school programs is down by more than 70% compared to 15 years ago, when the prison population was near its peak, according to a Connecticut Public review of annual reports published by DOC.

The shift isn’t completely unexpected. The prison population has dropped by about half since that time. Juvenile justice reforms also reduced the population of incarcerated teens.

But the decline in educational attainment has been steeper. The number of people who complete a high school level education is down by almost 90 percent. So is the number

of students promoted to higher class levels.

Staffing shortages have hindered enrollment, a DOC representative said in an email. The department has been working to refill teaching positions since a round of layoffs in 2016. It also grappled with teacher retirements and safety restrictions put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many incarcerated people were released during that time, leaving a smaller pool of potential students, according to the department.

Those under 18 who don’t have a high school diploma or GED are required to take classes while incarcerated in Connecticut. They’re typically enrolled in school in a matter of days, according to DOC.

Classes are voluntary for those 18 and older. The department acknowledged some adult students are put on waiting lists due to the teacher shortage.

It’s now adding more vocational training, and expanding efforts to recruit teachers. Part of that push is to do more hiring in the summer, when teachers are typically looking for work.

“It would be a disservice to our students if we did not make all efforts to replace teachers as soon as possible,” DOC spokesperson Andrius Banevicius wrote, “even if that means recruiting during unpopular times of the year.”

“However,” he added, “we are working closely with our HR unit to target our recruitment efforts to specific times throughout the year in order to recruit during the spring and summer months when most teachers are most likely to apply.”

GED testing goes online

Maria Pirro-Simmons was superintendent for the prison education system until 2020. She said she struggled with a tight budget and difficulty recruiting staff.

Another challenge came when the state started giving the GED exam online in the 2015-16 school year. Correctional facilities initially didn’t have enough computers or adequate space for testing during the transition, Pirro-Simmons said. The test also became significantly harder, leading to declining scores beyond prisons.

State data shows educational attainment in Connecticut prisons has been diminished ever since.

“Finding the staffing and the resources to support every prospective student in the Department of Correction was challenging,” Pirro-Simmons said.

Students who are incarcerated face other impediments, such as disruptive security lockdowns, which can interrupt academic programming.

It’s also challenging to have people in the classroom consistently, since being written up for disciplinary infractions can leave students ineligible for school, Pirro-Simmons said.

The DOC said the district is working with facility leaders to develop a system where disciplinary violations are reviewed on a case-by-case basis to keep students in their educational programs.

The school district now has GED computer labs available in 12 of its 13 schools. Staff transport students who reside at the one facility without a lab to another site on testing days.

Lawmakers ordered a study last year of how funding for the prison school system compares to other school districts. The report is still pending.

Kevin Devery teaches English at Manson Youth Institution, which houses boys and men under 21. Devery said he thinks prison education programs should get a higher priority in the state budget.

“That just strikes me as funny legislative bureaucracy and not the best financial policy and the best education policy,” he said.

‘Technology society’

For those who are released, educational programs also provide an opportunity to become acquainted with new technology.

Vernon Horn was wrongfully convicted at 17, and spent over a decade behind bars. Horn said he wasn’t sufficiently prepared for the changes in society when he got out. He had to navigate a new world of ubiquitous computers and smartphones.

“This world, this society, is a technology society,” he said. “Now, when I left … I called myself a dinosaur.”

He said the circumstances of being in prison make it hard for teachers to provide the education incarcerated people need.

“You got one teacher who comes in, jaded out, you know, she’s there, from the suburbs, around a bunch of people she thinks are guilty and a criminal,” he said. “So, I mean, in her mind, she probably can’t adequately teach us correctly.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.