The Prison Arts Initiative, a revolutionary arts and humanities collaboration between the University of Denver and the Colorado Department of Corrections that sparkled from national media acclaim and glowing reviews, has gone dark.

The programs were not renewed under a multiyear contract, and no one involved apparently is willing to say why.

“We have paused programming until fall, when we will seek input from faculty on what is next,” Jon Stone, DU’s director of media relations, said via email.

“We are grateful for the work we have been able to do together to enrich the lives of those who live in the Colorado Department of Corrections.”

The decision not to extend the contract for a fifth year was mutual between the two parties, Corrections spokesperson Alondra Gonzalez said, also by email.

The department “continues to prioritize arts programs in our facilities and will continue to explore new avenues to provide meaningful programming to those under our care.”

Other than those terse statements, secrecy and silence surround the Corrections-DU breakup. Some speculate that the separation had to do with an undisclosed violation of Corrections’ policies.

The Gazette’s requests for interviews about the termination were denied by the Department of Corrections, the University of Denver and the office of Gov. Jared Polis.

An open-records request The Gazette filed seeking email communication between key parties did not produce any documentation.

“A search was conducted for any and all emails between DU PAI and CDOC. There were no emails found within our 30-day retention policy, and we do not have records responsive to this portion of the request,” the denial stated.

Swing away from reform?

Some speculate that the Prison Arts Initiative was just one of several prison-reform measures in recent years to fall in the ongoing seesaw between prioritizing punishment or rehabilitation in the state’s prisons. Others think the situation could be an isolated incident and not indicative of a trend away from rehabilitative offerings for prisoners, which — the prevailing argument in favor goes — are designed to reduce recidivism.

Colorado’s one-year “return rate” hit a low of 8.8% in 2020 and crept up to 12.9% in 2022, according to state statistics. The one-year return rate in 2008 in Colorado was 32.9%. Colorado’s three-year return rate was 28% in 2020, the most recent year available from state data.

Regardless of cause, the loss of the initiative, which among other successes produced a traveling stage version of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” that caught the attention of The New York Times, was devastating for many.

“This program provided people a positive outlet, supporting them with creating art, theater, dance and lots of different avenues of expression,” said JoyBelle Phelan.

Formerly incarcerated for financial crimes, Phelan was released in December 2020 and landed a job with DU’s Prison Arts Initiative.

“It was community-minded, it brought people together by their interests and focused on doing something positive, which is always a benefit,” she said.

While incarcerated at La Vista Correctional Facility in Pueblo, Phelan took a 12-week course from the initiative that linked breathing with writing. It would change the course of her life.

“It was the first time anyone gave me a lot of positive reinforcement, especially about my writing,” Phelan said. “For me, writing in prison was transformative.”

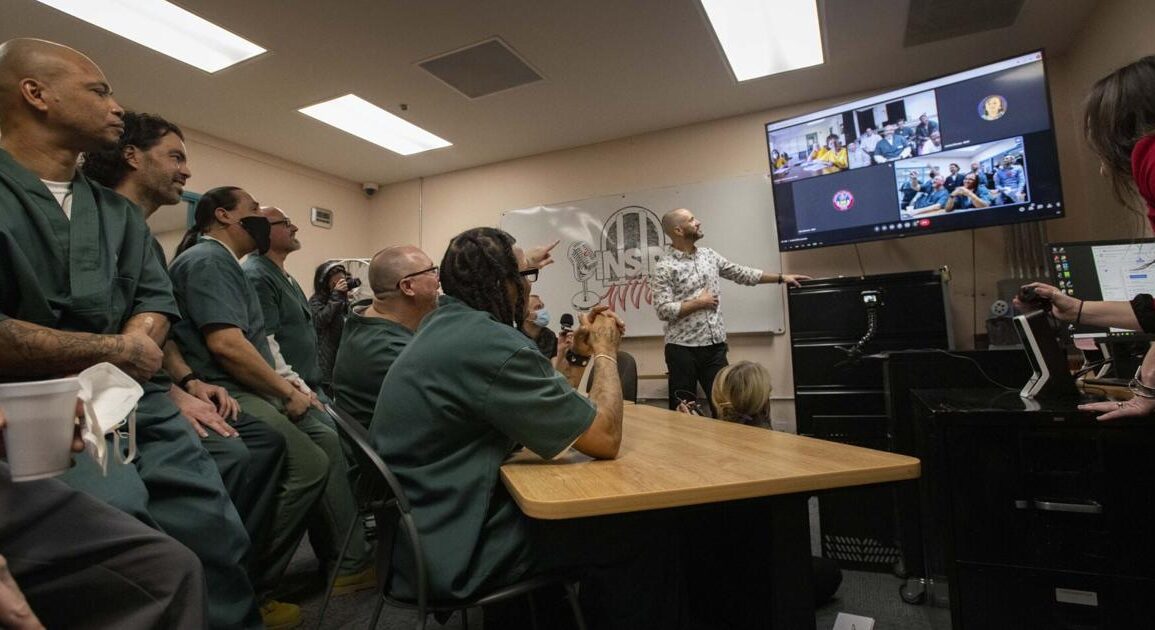

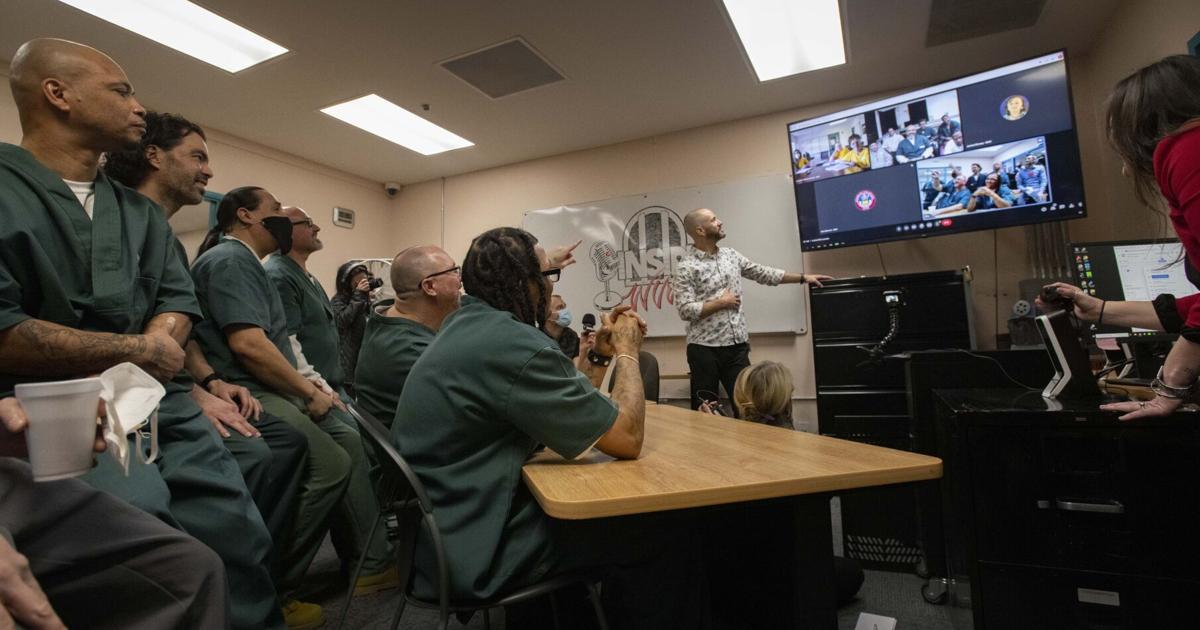

The curtain closed not only on theater, fine arts, music, literature and other cultural programs that reached prisons statewide through the Prison Arts Initiative. Also gone are Inside Wire: Colorado Prison Radio — the first radio station in the nation produced by inmates that was broadcast 24/7 to the public — along with an inmate newspaper named Inside Report and a podcast.

The radio station launched with production studios in several Colorado prisons in March 2022 and folded in the summer of 2023. The final issue of the prison newspaper was dated winter 2023.

Dean Williams, the former corrections chief who stepped down in late 2022, considers those projects among his biggest successes during his leadership. But they’re also tied to feelings of disappointment that they are gone.

“I never helped lead these initiatives with the promise they would last but am disappointed at the loss no less,” Williams said by email. “Some efforts and programs inside correctional systems ebb and flow with the politics of the season.”

Shroud of mystery

The contract between DU and Corrections expired last August and was not renewed, stunning many of those involved, by all accounts.

COVID-19 lockdowns initially curtailed programs that connected the outside with the inside, including a class that one source who asked to remain anonymous had been teaching inside the Fremont Correctional Facility in Florence.

Shortly after resuming classes as restrictions eased, he said he was told the class was being put back on hold due to inadequate staffing — although prison staff had not directly monitored his sessions previously.

That was two years ago, he said, adding, “I never even got to say goodbye to my students.”

Rumors surrounding the program’s demise pinpoint a suspected breach of Corrections policies that led to an investigation.

The nature and outcome of the investigation — if such an inquiry was conducted — remain unknown.

“People don’t have any answers, and that’s one of the hardest things — to lose something really valuable and you don’t know why,” another source said.

Meanwhile, DU’s Prison Arts Initiative’s website is unchanged, describing the initiative as “a robust program that brings arts-based, educational and therapeutic programming — covering numerous artistic modalities — into 12 prisons in Colorado and serves thousands of incarcerated people and their family members.”

One of three of its founders, Ashley Hamilton, who was the reigning executive director, still is featured on the website by name and title, but emails and phone calls to her requesting an interview went unanswered.

“As the contract came to an end, programming and staffing decreased appropriately,” Stone, the DU spokesperson, said in an email. “Dr. Hamilton has been offered an exciting opportunity to continue her community-engaged arts-based work in new ways, and we wish her well in this next chapter in her career.”

Hamilton’s online professional background says she started a new arts project with six incarcerated men called The Circle: A Center for Artistic Justice.

‘There were rumors‘

Kent, a 58-year-old Colorado native who was released from Fremont Correctional Facility in April after serving five years, kept the schedule for the prison radio station close to his heart while on the inside.

“I’d listen to older country and classic rock from when I grew up in the 1980s,” he said.

As the familiar music enveloped his consciousness, he’d reminisce about his days working the rodeo circuit before he was sent to prison for “the first go-round,” from 2002 to 2009. Back then, he’d get a “hobby permit” and buy things like glue, tape and poster board and build models of ships that he’d sell to prison staff to earn extra money to buy coffee or personal hygiene items, he said.

“When I went back in, you couldn’t do that anymore,” he said. “In Fremont, things were pretty strict, pretty hard.”

During his latest stint behind bars, Kent, who asked that his last name not be used out of respect for the victims in his case, also bought his family and friends Christmas and birthday cards made by prisoners who had taken classes through the Prison Arts Initiative.

“A lot of the guys were pretty bummed out about it when that program ended,” he said. “It was very popular. It gave people something to do, and there was a lot of talent in there, some seriously good artists.”

He remembers when the inmates heard that Williams was out as the corrections chief.

“We all predicted all the normalization that was starting to happen was going to go away, and we were right,” he said.

For a while, when Kent was incarcerated at Crowley County Correctional Facility in Olney Springs, prisoners who could afford to were allowed to buy clothing that was not institutionally issued, such as sweatpants, T-shirts and boots.

“Everything that did start to become a little more lax or comfortable went away, and it went back to being more punitive than anything else,” he said. “… There were rumors about us being able to wear regular clothes, buy food from the outside, have concerts. But that all went away when Williams went away.”

‘What had been progress’

For decades Mary Lynn Sheetz has run a transitional “halfway” housing and reintegration program in Colorado Springs for men exiting incarceration.

“We offer hospitality, a supportive environment with a little time to get their feet on the ground, make contact with family and move on with their lives,” she said.

Recently, Sheetz has seen what she describes as reform measures reverting to the point that she hasn’t been able to visit men in prison who are eligible for her program when they get out.

“This is horrible to have these changes, rolling back what had been progress,” she said.

“As those are being reversed, it’s really bad for both inmates coming out and the general population that have to accommodate them. The safety of our neighborhoods decreases when this happens.”

What Sheetz knows is beneficial after prisoners are released is this: “If we can get them involved in doing yard work for a senior, for example, they get a connection with life in the community, and their whole life changes.”

Sheetz is in the camp of those who believe the mindset governing Colorado’s 22 prisons has swung from a progressive, reform-minded philosophy under Williams, who was known for innovative ideas, to a conservative, punitive-focused approach under current Executive Director Moses “Andre” Stancil.

“Dean Williams was really doing some good stuff for preparing people to get back on the street,” Sheetz said.

“Now, we’ll get a person who’s been in 20 years, and they’ve had no rehab, nothing, and their PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) is terrible,” she said. “They have to meet appointments, get drug tested, often they can’t get jobs. We know guys who go to parole officers and say, ‘Please put me back in, I can’t handle it.’”

Polis appointed Stancil as interim head of Corrections in December 2022, after Williams announced his resignation in November of that year.

Polis moved Stancil into the executive director seat in January 2023. He had been with the department in other roles since 2019. Stancil declined to be interviewed for this story.

Some Corrections observers say Williams was forced out of his job that he held for one four-year term, but Polis’ office said at the time of Williams’ departure that one term had been the plan all along.

Before coming to Colorado, Williams had been removed from the chief position in Alaska prisons by the governor there after some of his reforms prompted controversy.

Williams also encountered resistance in Colorado.

Under Williams, the department pushed for work-release programs that housed inmates in minimum-security “halfway houses” while allowing them to pursue employment. The department also banned parole officers for seeking escape charges against parolees. Both decisions garnered criticism and were ultimately walked back.

Williams declined to speak about the circumstances surrounding his departure but reiterated via email that his normalization efforts and removing the “us” vs. “them” mentality are proven to improve not only the lives of prisoners but also the prevailing culture.

“In both state correctional systems that I led in Alaska and Colorado, I took the firm approach that programs behind the walls were the best way to assure safety for staff and inmates, and the public as well,” Williams said.

He said he worked to expand purpose and opportunities for incarcerated men and women because “idle time inside prison is a danger to everyone — staff, inmates and the public.”

Creating normalization

Founded in 2017 by three higher-education professionals who wanted to improve the quality of inmates’ lives and prepare them for making a positive impact after their release, the University of Denver’s Prison Arts Initiative landed what was lauded as an unprecedented contract with the Department of Corrections in 2019.

The initial $326,300 contract, obtained through a public-records request, was extended four times totaling $2.4 million, until it expired last August.

The purpose: “To create normalization initiatives and programming to teach pro-social behavior that impacts the culture and climate for offenders to develop life skill concepts in an art-based format of delivery.”

While Corrections denied an interview with Stancil, Gonzalez, the department spokesperson, provided a few answers to some questions via email.

It’s important to note, Gonzalez said, that the initial contract term was set to conclude on June 30, 2020.

“The Colorado Department of Corrections recognizes the positive impact the program has had on many of its participants, and although we no longer have DU PAI programming, we continue to provide various programs and services to our incarcerated population,” she said.

Gonzalez cited as some examples offerings of academic courses, social and behavioral science courses, peer advocacy, career and technical education, industry trade training and faith-based and citizen-driven programs throughout the facilities.

Current opportunities in the arts include drawing, ceramics, sculpture, printmaking, music lessons and performances, dance and theater, a crochet club, life-skills instruction and more. Some are led by inmates, others by professionals in the community, Gonzalez said.

It’s hard to say exactly what’s going on with the corrections system, said Christie Donner, founder and executive director of Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, which advocates for “more effective and just” public safety strategies.

“Is it about Director Stancil, is it anti-reform, or is this just a new reality where they say they’re fine, and we say they’re in crisis?” she posed.

A study her organization released in January, providing results from 400 prisoners about conditions on the inside regarding quality of life and health and safety concerns, speaks of critical staff shortages in Colorado’s prisons.

Some positions are showing upward of 40% vacancy, including medical and behavioral health care clinicians, which are high needs for prisoners.

The state has tried to address the shortages by increasing overtime of existing employees, reassigning teachers and case managers to correctional posts, lowering the hiring age to 18, and allocating more tax dollars to the system.

“They’ve made some progress, but how much of it is because of lowering the standards for hiring?” Donner said.

The shortage of employees trickles down to programming, she said.

“That’s going to have a significant disruptive effect on any programming,” she said, “and we’re concerned about that. We’re hearing some programs are not being allowed in because they don’t have the staff. I don’t think it’s a complete unwinding of those partnerships, but I have definitely heard they’ve reduced the numbers or weren’t open to new programs.”

Williams said, while leading the department, his goal was to set an expectation that an inmate should progress in personal responsibility and maturity while incarcerated, and he used programming to achieve that end.

“Programs provide an opportunity to learn and practice that,” he said. Otherwise, “Prison becomes a training ground for advancing criminality instead of a place for redemption.

“In many ways we’ve never made up our mind on what we want prisons to do. To rehabilitate or punish?”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.