When most people think about companies profiting from the U.S. criminal justice system, private prisons are likely the first thing that comes to mind, but that’s only the tip of the iceberg. More than 1.2 million people are incarcerated across the United States. The vast majority of them — more than 90 percent — are housed in public prisons run by states and the federal government, at an average annual cost of more than $40,000 per person.

“It costs as much to send someone to prison as it does to send them to college,” said Tanay Tatum-Edwards, CEO and founder of FreeCap Financial. “And that money is all going somewhere.”

We know more about exactly where it’s going thanks to new research from FreeCap Financial, and the data provider has more insights to come this spring. Armed with this information, asset managers can better understand how the companies in their portfolios interact with the criminal justice system and ensure their investments align with their clients’ values.

“Capital markets aren’t the solution to all problems,” Tatum-Edwards said. But when it comes to the mass incarceration system that leaves around 1 in 3 U.S. adults with a criminal record that would appear on a routine background check for a job, “this is actually one problem where we can’t fix it without fixing the profit incentives that drive it,” she said.

More than $8.6 billion in profit from prisons

FreeCap‘s Prison Vending Relationship Dataset, released earlier this year, aggregates payments between the 3,000 largest publicly-traded U.S. companies and corrections departments across the country.

“Thanks to the Freedom of Information Act, states now publish which companies they have contracts with at a department level, so we started gathering state transactional data between corrections departments and companies in the entire Russell 3,000 to see how much money companies were making off of vending contracts with prisons,” Tatum-Edwards said. “This is, to my knowledge, the only dataset that actually quantifies how much money companies make off of prisons.”

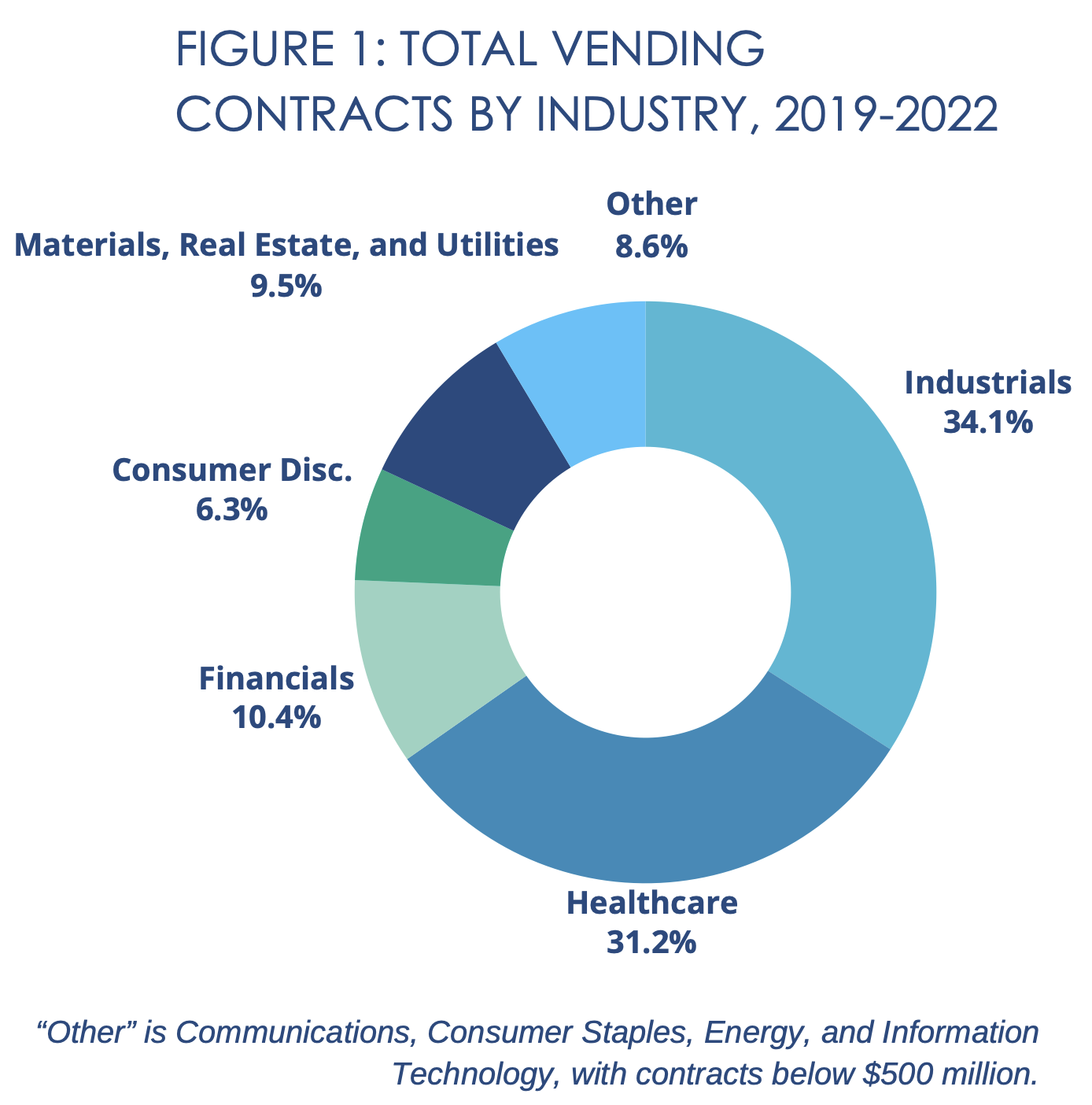

The big total? The companies in the Russell 3,000 Index made more than $8.6 billion from state and federal prison contracts between 2019 and 2022, according to FreeCap’s analysis of data from state comptrollers’ offices, the Federal Bureau of Prison Comptrollers and the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

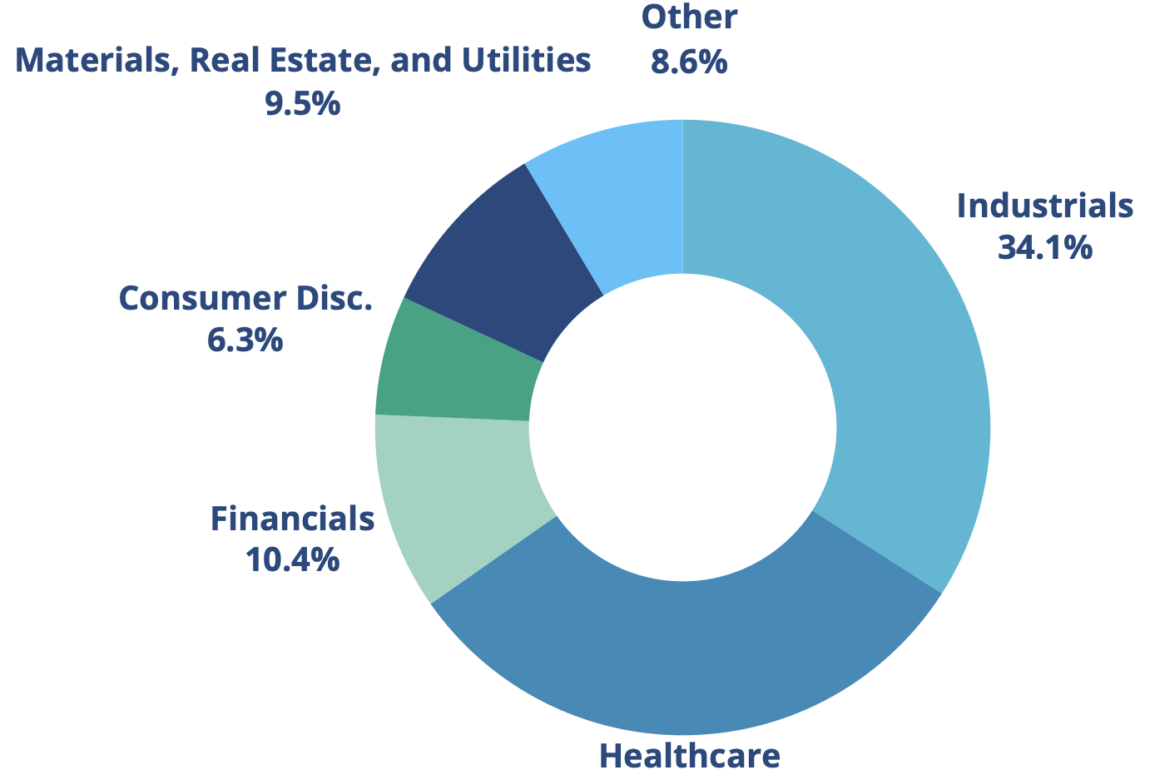

Contracts tracked in the dataset span industries including healthcare, financial services, real estate and consumer goods. The largest share of state and federal prison contracts went to the industrials sector, which includes logistics companies and utilities.

Beyond prison contracts: Other ways companies impact mass incarceration

The Prison Vending Relationship Dataset appears within FreeCap’s 2023 Criminal Justice Report. Along with the findings on prison contract relationships, the report details other ways companies directly or indirectly fuel the system of mass incarceration.

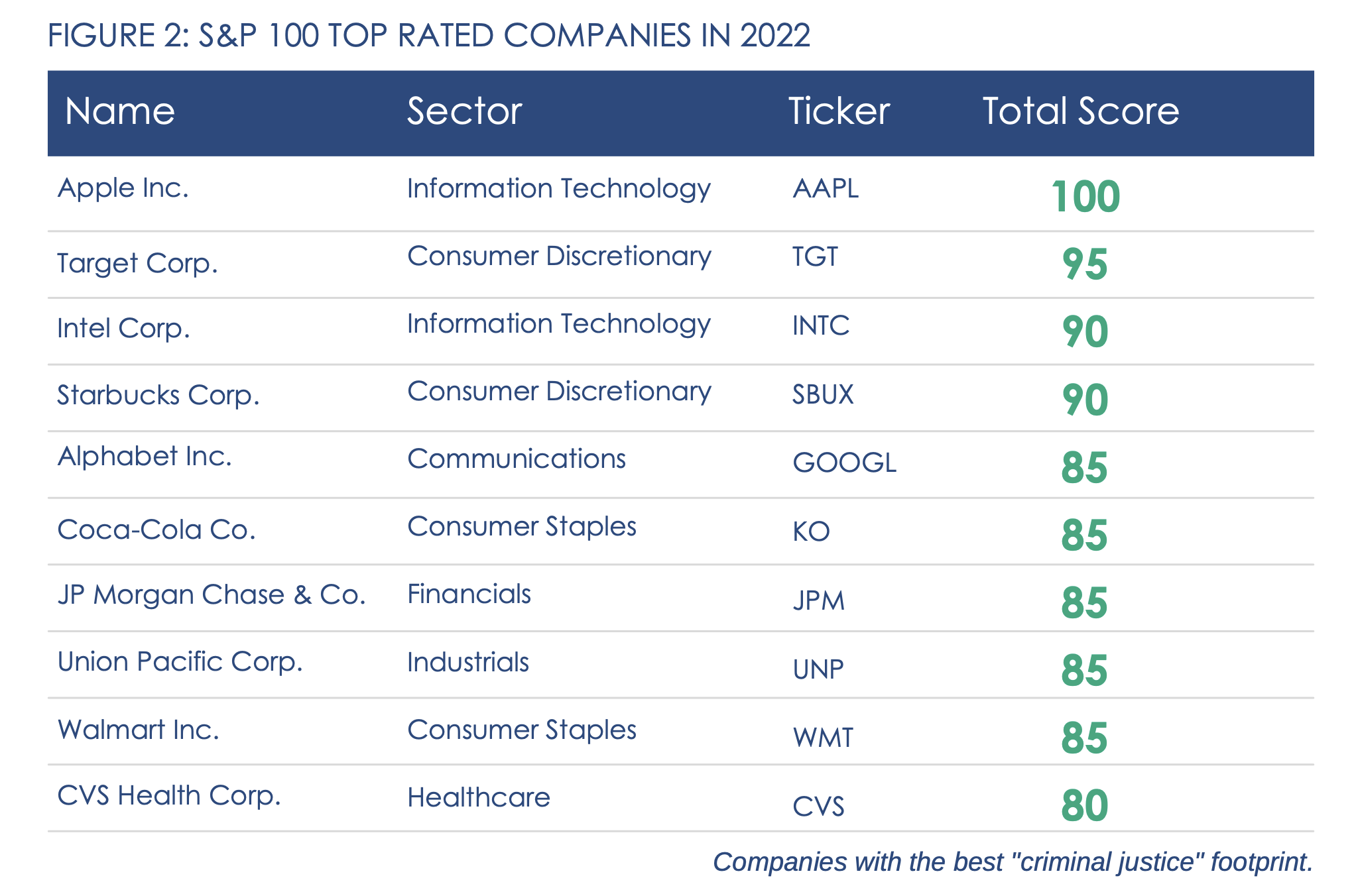

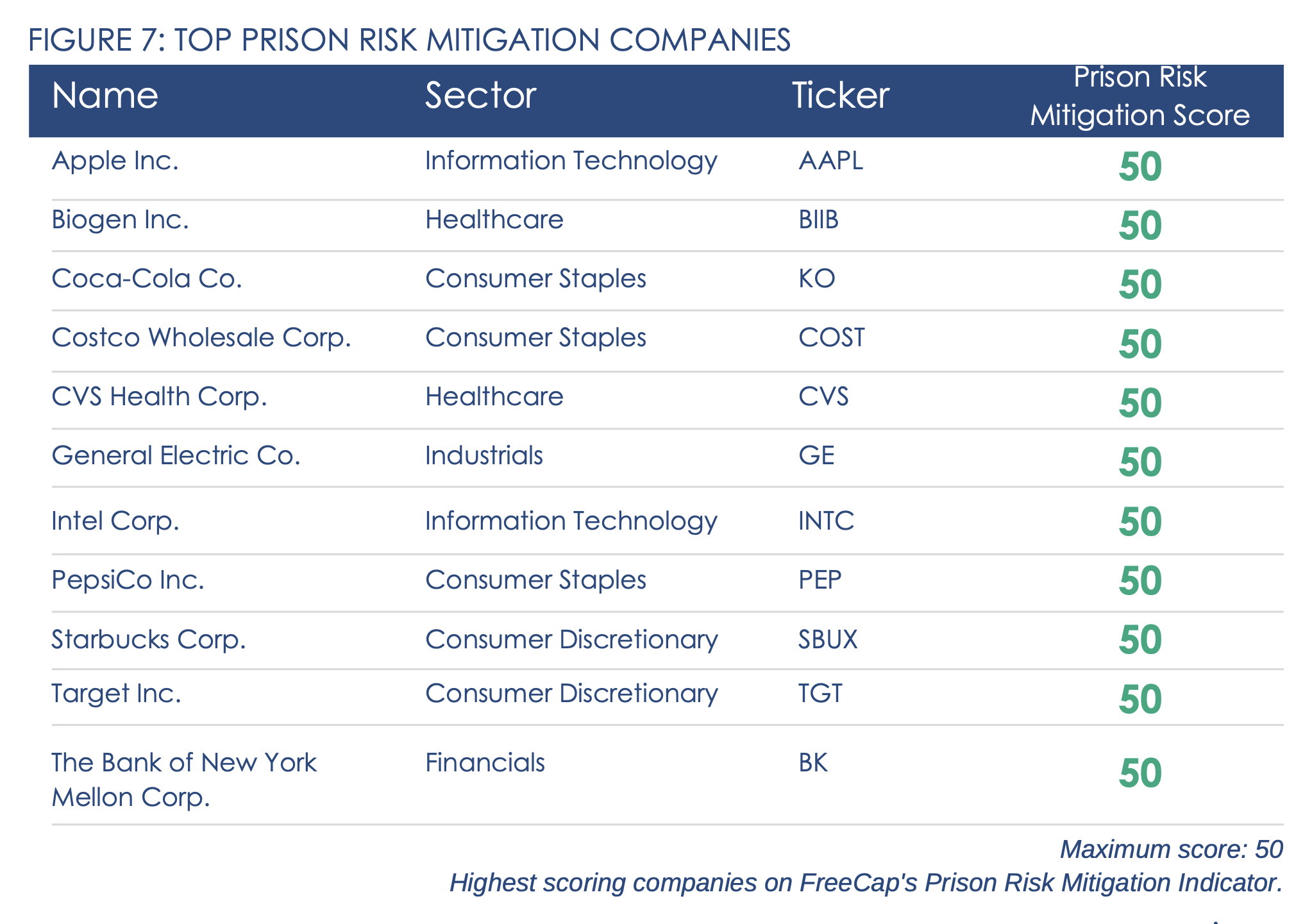

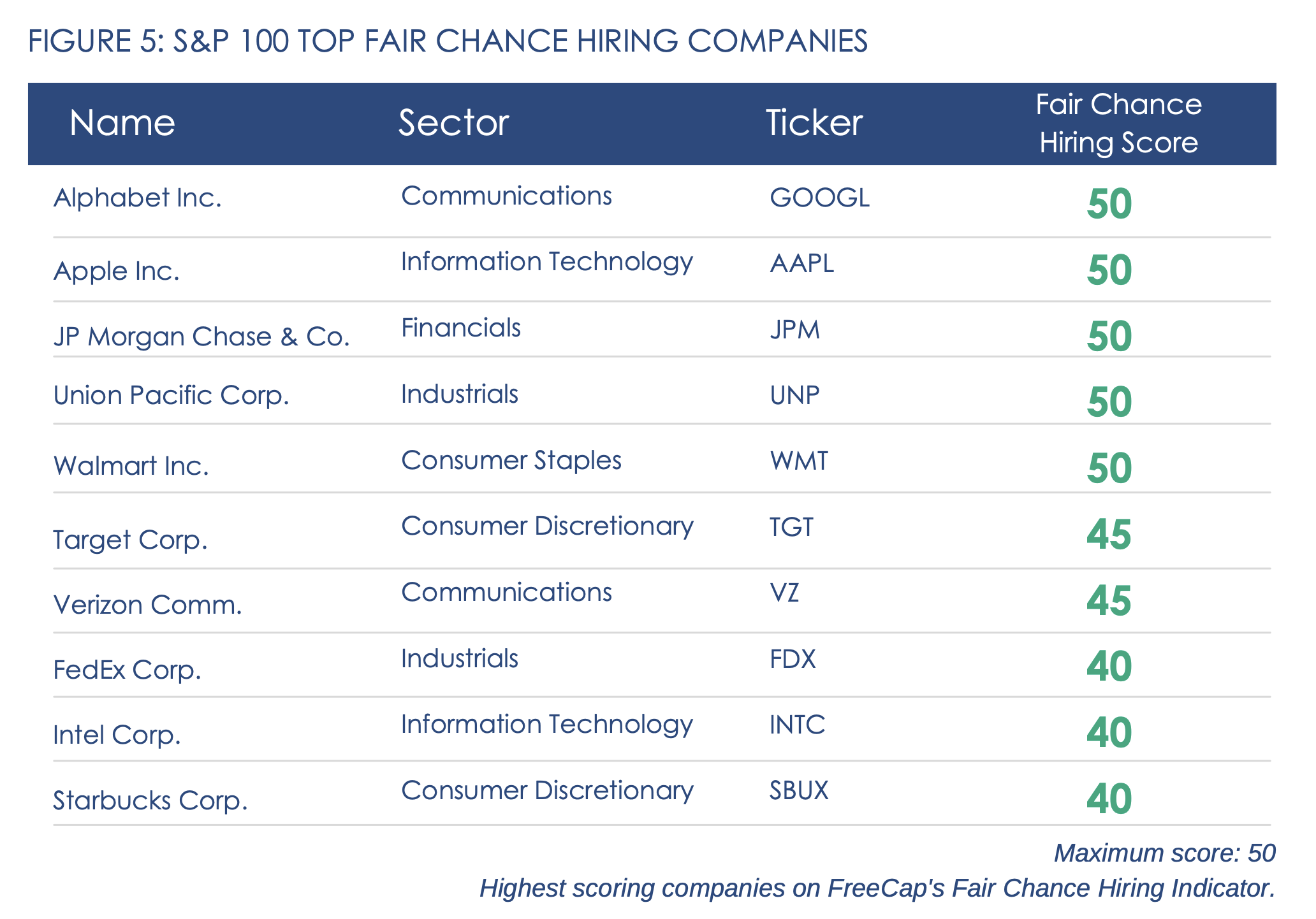

Specifically, FreeCap analyzes corporate supply chain policies around the use of prison labor, as well as hiring policies for people who are justice-impacted, to create a scorecard ranking for use by asset managers. The report covers the 105 largest U.S. companies in the S&P 100, and a follow-up that ranks the entire S&P 500 is expected in April.

Prison labor in U.S. supply chains presents major business risk

It may come as a surprise to consumers and investors that less than a fifth of companies in the S&P 100 explicitly ban the use of prison labor. Even fewer have policies in place to identify the potential risks of prison labor in their supply chains.

“The vast majority of companies will ban forced labor, but because prison labor is legal under the 13th Amendment in the U.S., in order for prison labor to be covered by company policy, they have to be explicit about it,” Tatum-Edwards said. “The U.N. best practices around forced labor don’t actually cover U.S. prison labor, [although] most folks in prison are making less than a dollar a day.”

By not adding language about prison labor to their supply chain codes of conduct, companies leave themselves exposed to reputational risks that could follow them for decades. Some of the companies that score the highest on FreeCap’s rankings are actually those that faced blowback from their shareholders and customers over links to prison labor in the past. Though they responded by enacting clear policies and audit procedures, landing them top ranks on FreeCap’s list, many of these companies are still linked to prison labor in the media to this day.

“Starbucks is a great example of that,” Tatum-Edwards said. After being alerted to prison labor in its supply chain, Starbucks explicitly banned it in 2006, but new articles linking the coffee chain to prison labor still pop up a few times a year, prompting the company to issue new statements and social media posts about its nearly two-decades-old ban.

“Because they had that exposure at one point, they have to spend a lot of resources convincing the public that they’re not in that space,” Tatum-Edwards said. “And because of that, we actually see them as having some of the more strict prison labor policies in our database.”

Companies would be wise to learn from experiences like these and address their potential exposure to prison labor before they’re subject to stakeholder backlash. “Something as easy as simply explicitly banning prison labor in all of its forms in your supplier code of conduct policy means that any subcontractor who is using prison labor is in violation of that,” Tatum-Edwards said.

Fair chance hiring offers a labor opportunity

On the other end of the spectrum from prison labor risk, fair chance hiring policies for people with criminal justice histories present a major labor market opportunity.

More than 85 million jobs could go unfilled by 2030 due to a shortage of skilled workers, according to 2023 research from Korn Ferry. “But when you look at the number of people who have records, who are systematically discriminated against in the job market, that number is 70 million,” Tatum-Edwards said. “Some of these companies have realized that in order for them to be able to remain competitive from a labor perspective, they have to figure out how they can actually hire people who have been involved with the Justice Department or else they are not going to have talent at all.”

FreeCap measures corporate performance on fair chance hiring based on factors like whether background screenings are applied before or after the initial job offer, as well as whether a criminal record automatically disqualifies someone from employment without further consideration. It also looks at whether companies have programs in place to actively recruit or train people with criminal justice histories.

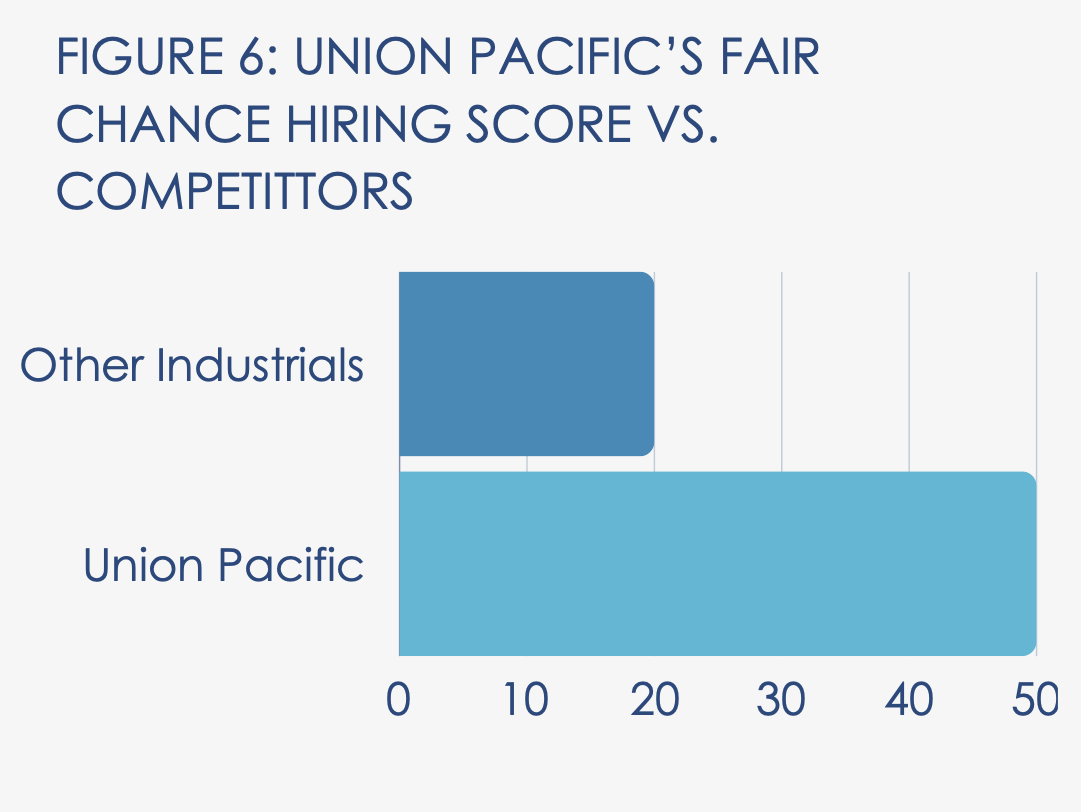

Five companies — Apple, JPMorgan Chase, Walmart, Union Pacific and Google parent company Alphabet — received perfect scores for their efforts to promote fair chance hiring. FreeCap highlighted the freight company Union Pacific in particular, which is part of the industrials sector that is most exposed to prison risk, for its leading programs to minimize that risk and recruit people with records.

“The fair chance hiring piece is huge,” Tatum-Edwards said. “Companies need to do it for their bottom lines and it’s also good for society, so it’s one of those win-wins where everyone should be investing resources into it.”

Still, progress is still slow, with less than a third of the S&P 100 making public commitments to support fair chance hiring, the same amount FairCap observed in 2021.

Why should investors care about this?

“There’s these trends showing that companies who engage in fair chance hiring are going to remain competitive, and folks who are profiting off of prison are engaging in reputational risk,” Tatum-Edwards said. “Decarceration is one of the only issue areas that’s actually bipartisan. People love police, but people don’t love prisons. And so if you are looking at those trends, companies whose business models are fixed around and rely upon profiting off of prisons are going to have trouble as incarceration decreases.”

FreeCap’s work aims to turn observations like these into objective datasets asset managers can use to reduce their exposure to prison risk and drive more values-based investment.

Due to be released next month on investment, the FreeCap Index will rank the best performers in the S&P 500 across criminal justice factors, allowing asset managers — and everyday stockholders — to make evidence-based decisions about prison risk.

“We vote with our dollars every day,” Tatum-Edwards said. “This will make it easier for people to see exactly how to invest based on this factor.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.