This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman.

A legal battle is continuing between the Trump administration and a federal judge over the president’s invocation of the 1798 Alien Enemies Act to expel over 130 Venezuelan immigrants from the United States to a maximum-security prison in El Salvador.

CBS reports new court filings suggest the administration may invoke its state secrets privilege to block requests from D.C. District Chief Judge James Boasberg for more information about what happened Saturday when the Trump administration ignored the judge’s order to turn around three flights headed to El Salvador. It’s not clear if one of the flights had even left the tarmac.

The Trump administration claims all the men sent under the Alien Enemies Act were members of a Venezuelan gang, but a growing number of press accounts cast doubt on Trump’s claims.

We’re joined here in New York by Margaret Cargioli, directing attorney of policy and advocacy at Immigrant Defenders Law Center, which is representing an LGBTQ Venezuelan asylum seeker who was flown to El Salvador even though he did not have a deportation order. We’re also joined in Washington, D.C., by Juan Pappier, Americas deputy director at Human Rights Watch. He’s investigated the prison system in El Salvador.

Margaret Cargioli, let’s begin with you. Tell us about the person who was sent to the maximum-security prison in El Salvador.

MARGARET CARGIOLI: Our client is in asylum seeker who entered the United States via the U.S. southern border through the CBP One app over a year ago. He was detained in Southern California, was waiting for his right to have, you know, a judge hear his case as to asylum. He was flagged because he has tattoos — he’s in the arts field — solely because he has tattoos. The only evidence that the government at that point had submitted were pictures of what they attribute Tren de Aragua gang members to have, just one page of a few tattoos. And solely because of that, having no criminal record, he has been sent to a very dangerous place where we fear for his safety.

AMY GOODMAN: You don’t want to use his name. Why?

MARGARET CARGIOLI: We are seriously concerned for his well-being, his safety, and he is an asylum seeker. He fled Venezuela because of persecution. And so we have to keep some of the details of his case private.

And it’s extremely concerning that the United States government is not sharing any information. We did not know his whereabouts from Friday until Monday, when he had an immigration court hearing. At that hearing was the first time that the United States government actually confirmed that he was sent to El Salvador.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, just to understand, he was deported — would you use that term, “deported”? — even though there was no order of deportation?

MARGARET CARGIOLI: There was no order of deportation. There was no order of removal. He was not deported. He was sent there unlawfully. He still has a pending immigration court hearing. It’s coming up very soon. And he has a right to seek asylum. What happened here is extremely unusual and concerning.

AMY GOODMAN: So, my question is: Why was he sent to — among many other questions — El Salvador? Juan Pappier, if you can talk, from your Human Rights Watch perspective, about this prison, this supermax prison, CECOT, in San Salvador that these prisoners have been sent to, and the deal the Trump administration has made with their ally, the president of El Salvador, with Bukele?

JUAN PAPPIER: Amy, thank you for having me.

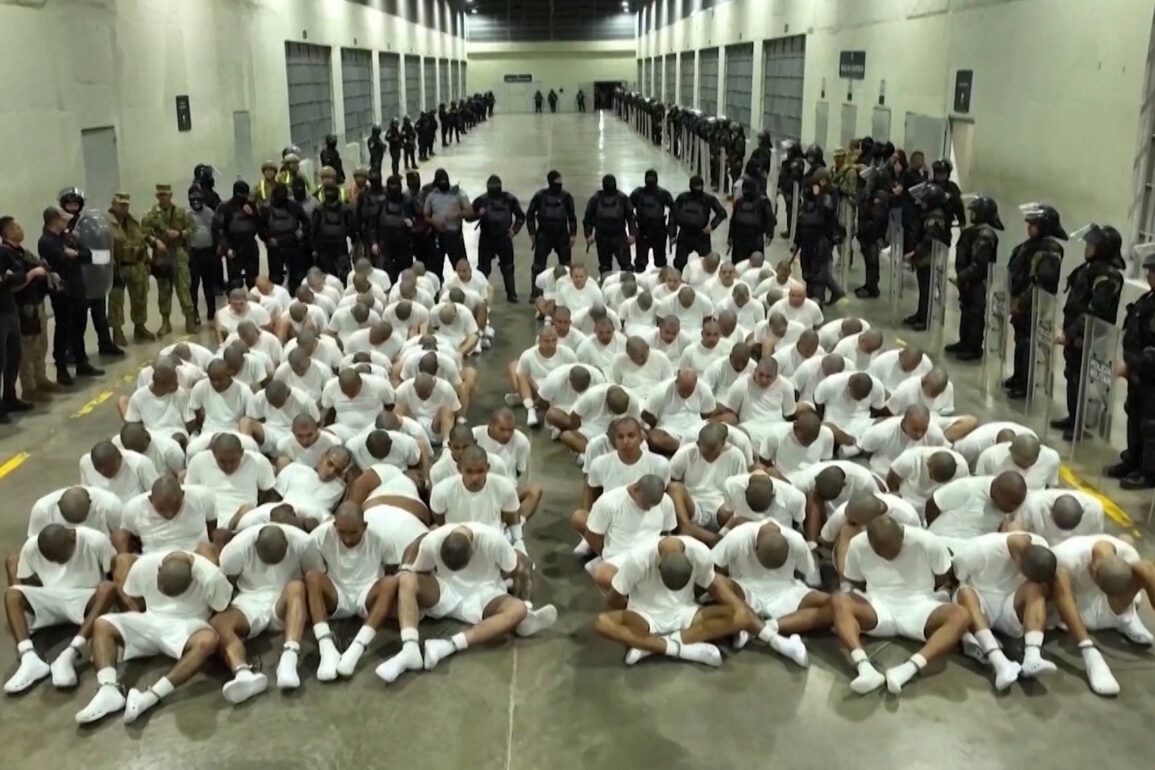

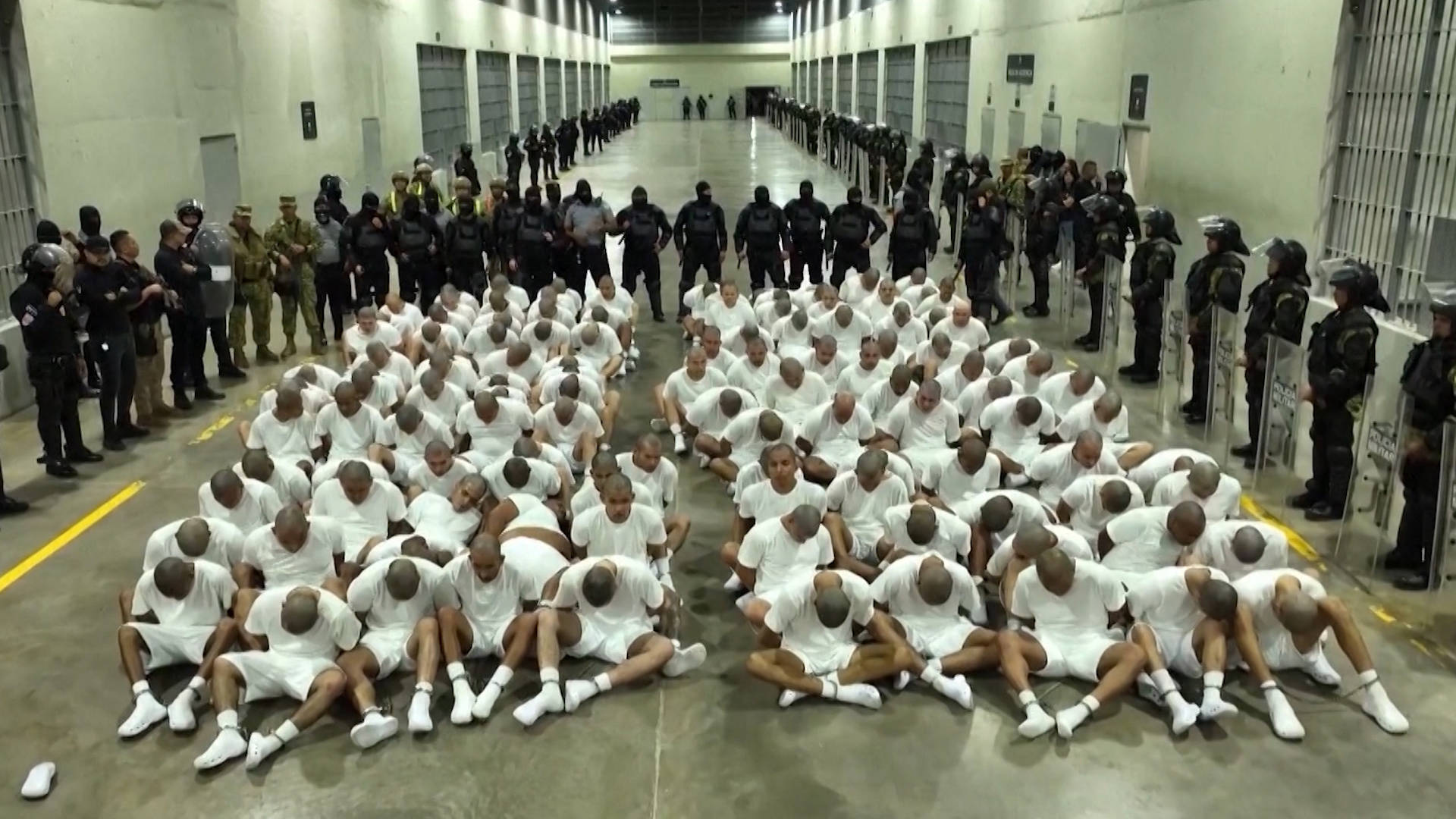

The CECOT, the Center for Confinement of Terrorists in El Salvador, is a mega-prison, inaugurated in 2023. It was initially announced for 20,000 detainees, and the president then doubled the capacity to 40,000 detainees. It has 256 cells, where detainees are expected to share a bed. And the access to the media and to human rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch, is severely restricted. And the government has publicly said that people who are sent to the CECOT will never be allowed out. We have not been able to identify any detainees who have left CECOT.

But we have every reason to believe that people held there are subject to the similar treatment as in other prisons in El Salvador — that is, torture, deaths in prison and enforced disappearances. People in CECOT are completely cut off from the rest of the world and denied any legal — any meaningful access to legal recourse. This is an effort to create a Guantánamo on steroids, to put these people outside of the protections of the law both in the United States and in El Salvador.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let’s talk about — in 2023, the U.S. State Department report noted El Salvador had harsh and life-threatening prison conditions. Can you talk about your thoughts as the Trump administration has agreed to pay the government of President Nayib Bukele $6 million for a year of services to accept people removed forcefully from the United States, as this lawyer, Margaret Cargioli, is describing, disappeared from the United States?

JUAN PAPPIER: This is an open violation of the United States’ obligations under international law, because they are sending people to a place where they have serious risk of being tortured and subject to human rights violations, in addition to the violations by denying them the possibility of seeking asylum in the United States. We have documented in prisons in El Salvador cases of torture, of enforced disappearances, conditions in detention that are dismal, and massive arbitrary arrests of people who have nothing to do with the gangs in El Salvador who are being held in these prisons, as well. These are dismal conditions in these prisons, and I am very worried about the safety of these migrants who have been sent there. It’s worth noting that the governments of the United States and El Salvador have not released a list of people sent there, nor any indications that they effectively are part of the Venezuelan gang known as Tren de Aragua.

AMY GOODMAN: What, something like 261 people died in El Salvador’s prisons? Can you talk about – just last year. Can you talk about what you know about the torture, the lack of medical attention, the abuse that occurs, not only at CECOT, but in these other prisons that the U.S. has now made a deal with the president of Salvador to house U.S. prisoners?

JUAN PAPPIER: Local human rights groups in El Salvador have recorded 350 cases of detainees who have died in prisons since March 2022, when a state of emergency began in El Salvador. The country has been in this state of emergency for three years now. That means that constitutional due process rights are suspended.

And we at Human Rights Watch have documented many of the cases of people who died in prison, and we have identified evidence of state responsibility of some of these deaths. We have reviewed these cases with forensic experts and identified evidence of possible torture leading to some of these violations. These are the conditions where these people are being held, that are, as the State Department held in its 2023 report on human rights, life-threatening. So I think it’s very shameful to see Secretary of State Rubio say that these are very good prisons. These are prisons with life-threatening conditions.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Margaret Cargioli, have you talked to your client?

MARGARET CARGIOLI: We have not been able to speak to our client. We did reach out to the Department of Homeland Security and yesterday were told that they cannot facilitate communication with our client because he’s been removed.

We are hoping that, with public pressure and through federal litigation, we are able to soon talk to our client, find out information as to exactly where he is, you know, what conditions he’s being held under, and also to find out exactly what transpired. How is it that an asylum seeker, detained in the United States, with an immigration attorney, disappears for several days and ends up in a maximum-security prison in a third country?

AMY GOODMAN: Can federal Judge Boasberg, who is hearing, trying to get answers from the U.S. government — Pam Bondi, the attorney general, says they don’t have to respond with specific answers about how these deportations have happened. Can he play a role in getting your client back?

MARGARET CARGIOLI: Yes, our client actually is — does fit under the class within that lawsuit. So we’re hoping that, through litigation, we will be able to have our client return to the United States. The United States government has to comply with the law. They have to comply with federal court law rulings. And we know that the judge is reviewing the case as to whether the government is in contempt of court for not complying with its rulings and information that it’s sought.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we’ll continue to follow this case. Margaret Cargioli is directing attorney of policy and advocacy at Immigrant Defenders Law Center, speaking to us here in New York. And Juan Pappier, Americas deputy director at Human Rights Watch, speaking to us from Washington, D.C.

That does it for our show. Happy birthday to Tami Woronoff! To see all transcripts, podcasts, video and audio podcasts, you can go to democracynow.org, and also sign up there for our daily newsletter. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.