“Dead Man Walking” at Sing Sing

The epigraph to Sister Helen Prejean’s book “Dead Man Walking,” published in 1993, is from “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”: “I went right along, not fixing up any particular plan, but just trusting in Providence to put the right words in my mouth when the time come: for I’d noticed that Providence did always put the right words in my mouth, if I left it alone.” Those lines signalled that this work by a Roman Catholic nun was literary, worldly, and irreverent in its way, and with a distinct regional tang—a story of life in her native Louisiana and the part of the country she called the Death Belt, where state executions were carried out and celebrated.

The suggestion that Prejean herself sought “the right words” with “no particular plan” seems an augury for her book’s eventual reception. Born in Baton Rouge in 1939, a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph since her late teens, and trained as a schoolteacher, Prejean sought to renew her religious life at the age of forty, by going with several other sisters to work with the residents of a New Orleans housing project and live nearby. Invited by a person whom she met there to correspond with men on death row at the notorious Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola, she became a regular visitor, and the spiritual adviser (a role now protected by the Supreme Court) to two men whose executions were imminent: Elmo Patrick Sonnier, who, when invited to say his last words in the execution chamber, asked the father of one of his murder victims, who was looking on, to forgive him; and Robert Lee Willie, a white supremacist who was resolute in showing no remorse for the crimes he had committed. An unexpected best-seller, the book soon became a standard text for anti-death-penalty activists and a staple of high-school and college reading lists. A 1995 film adaptation, starring Susan Sarandon (who won an Oscar for her performance), eventually made Sister Helen, as she is known, a celebrity and a model for a justice-seeking Catholic in a period when the Church was disgraced by revelations of clerical sexual abuse.

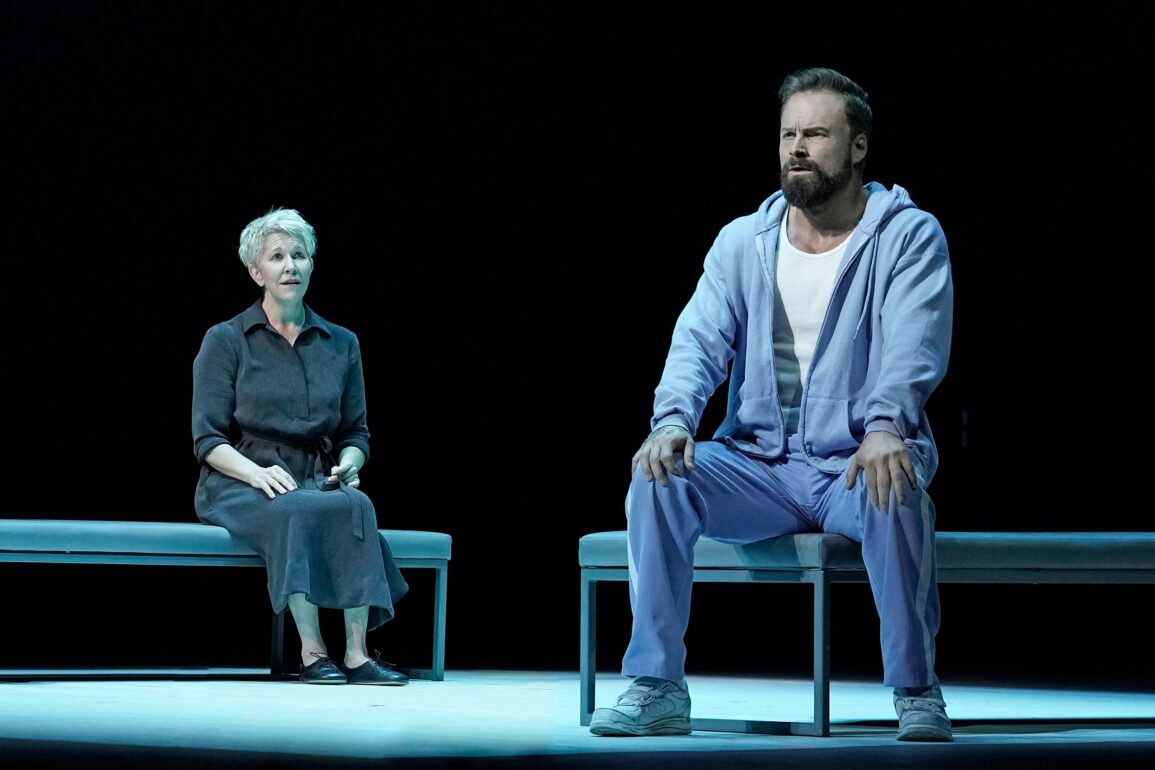

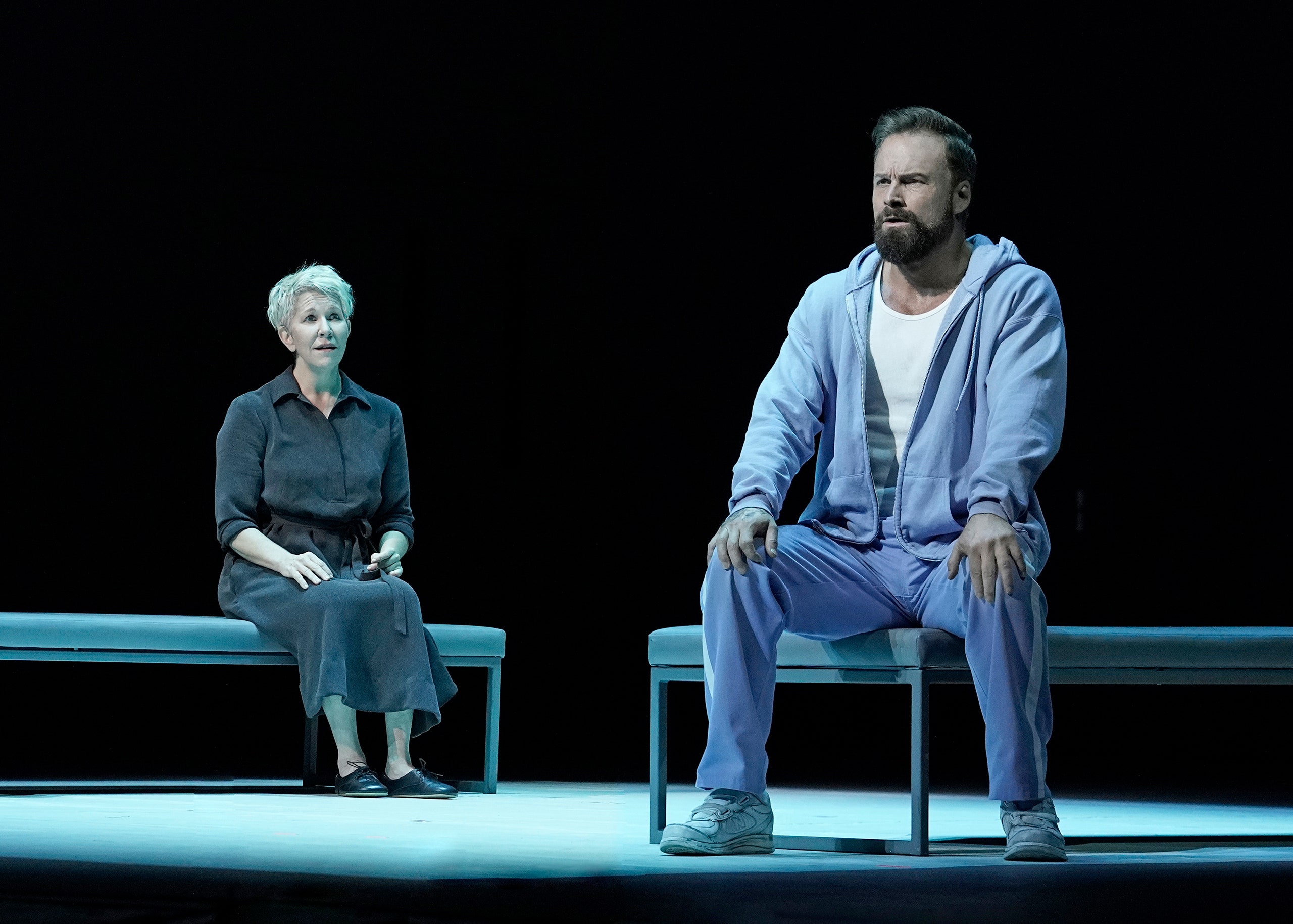

An opera based on the book, with music by Jake Heggie and lyrics by Terrence McNally, had its première at the San Francisco Opera in 2000, and has since had more than seventy productions in the U.S. and around the world, including, in 2002, at the New York City Opera. “Dead Man Walking” is, according to the Metropolitan Opera, “easily the most performed contemporary opera of the twenty-first century,” and on Tuesday night a new production, directed by Ivo van Hove, opened that company’s 2023-24 season. The mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato, who has performed with the Met since 2005, sings the role of Sister Helen, as she has done three times before, including at the City Opera. The bass-baritone Ryan McKinny sings the role of a man on death row whom Prejean advises named Joseph De Rocher—he is a fictionalized composite character—which McKinny also performed in 2019 at the Lyric Opera, in Chicago.

The run-up to the Met première was thoroughly out of the ordinary. A final dress rehearsal this past Friday afternoon was followed by a reception where the principals mingled with Prejean and a group of anti-death-penalty activists she had invited along. Elizabeth Zitrin, a senior adviser to and the past president of the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty, reminded everyone that the United States is the fifth-most-active executioner among nations, after China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. Then Prejean and her guests walked down the block to Fordham University’s Manhattan campus, to discuss the state of the movement with students. (“Sister Helen and a hundred and fifty of her closest friends,” as David Gibson, the director of Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture, put it to me.) And, on Thursday, DiDonato and members of the company will perform excerpts from the opera at Sing Sing Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison about thirty miles north of New York City, accompanied by a chorus of incarcerated men.

Those who know Prejean’s story through her book will find the opera substantially new. I teach the book in a course at Georgetown every fall, and I invite students to identify all the things it is: a work of true-crime nonfiction, a conversion story, a guide through the capital-punishment bureaucracy (charges, convictions, appeals, requests for clemency), a record of the roots of the death penalty in slavery and racism, an anguished encounter with murder victims’ families, and an urgent argument that no one should die at the hands of the state. Like the film, the opera, while touching on each of these themes, is a drama of redemption, with Prejean, as DiDonato says in a short video on social media, “trying to bring the spiritual salvation of this man who’s asked for her help.” Where the book is earthy and idiomatic (nun and inmate “talk regular” to each other), the opera is a tightly wound, stylized works. And where, in the book, death-row protocols forbid Prejean and Sonnier all but a last (and first) embrace, the Met production is intimate, with no bars, plexiglass barriers, or handcuffs. “There was more touching in this one than I’ve ever seen,” Prejean told me, in her strong Louisiana accent. “A lotta, lotta touching.”

Prejean is eighty-four now; she has served as a spiritual adviser to several dozen people on death row and witnessed six executions, all of men she knew. Nonetheless, it’s strange, she said, to see and hear a new rendering of her initiation into death-penalty work, an experience which stirred emotions of fear and disorientation that are still fresh in her memory. “I thought I was just going to be writing letters,” she said, “and then, boing, it hits me: ‘I was imprisoned, and you came to me.’ That’s the gospel. That’s what we’re supposed to do. So that’s what I did.” She is now one of the world’s most prominent opponents of capital punishment. Forty-three countries and eleven U.S. states have abolished or ceased to practice capital punishment in this century—developments that she has often helped bring about, through dealings with politicians and civic leaders, or has brought to public attention, through her writing and speaking. This summer, she joined an effort to urge Louisiana’s Democratic governor, John Bel Edwards, to commute the sentences of the more than fifty people on the state’s death row when he leaves office (owing to term limits) early next year.

On Saturday morning, Prejean and DiDonato went to Sing Sing, for a rehearsal ahead of Thursday’s performance, which will be for an audience of some two hundred men incarcerated there. DiDonato grew up in a large Catholic family in Kansas; an uncle, Edward Flaherty, was a Jesuit priest, and conversations at the family dinner table, she told me, often focussed on questions of vocation and service. For the past eight years, working with Musical Connections, a program sponsored by Carnegie Hall, she has gone to the prison periodically to work with a group of men known as the Musical Connections Resident Ensemble, singing opera and art songs for them and with them. When “Dead Man Walking,” which was originally scheduled as part of the Met’s 2021 season, was coming together, following the pandemic, DiDonato looked into how she could bring that work to the prison. “This material is their material,” she told me, and later explained, “It’s a story that’s deeply painful and personal. For them to open themselves to it is an act of bravery.”

Sing Sing, in Ossining, on the east bank of the Hudson River, was built beginning in 1825, by prison labor; its location is the basis for the expression to be “sent up the river.” Sing Sing’s “death house” was the dedicated site of executions in New York: more than six hundred of them between 1891 and 1963, the year of the last legal execution in the state. The most infamous were of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were both sent to the electric chair on June 19, 1953, having been convicted on espionage charges for passing details of the atomic-weapons program to the Soviet Union. In 2004, the New York Court of Appeals abolished the death penalty, and there is currently no one on death row in the state prison system. The “death house” is now a place where the seventeen hundred men incarcerated in the prison can gain vocational skills.

After passing a series of checkpoints, the rehearsal group was shown into an old auditorium. Prejean, DiDonato, a Met keyboardist, and the local state assemblywoman, Dana Levenberg, sat in chairs in a circle on the stage with a dozen members of the Musical Connections Resident Ensemble, who introduced themselves to Prejean. They wore prison-issue green pants, and shirts evidently of their own choosing: tennis shirts, sweatshirts, T-shirts, hoodies The men were white, Black, and Latino, and appeared to range in age from about twenty-five to sixty. One introduced himself as a cellist, another as a spoken-word artist, a third as an aspiring saxophonist. From all appearances, they might have come together for an adult-education program at a community college. But one man spoke of serving a life sentence without parole; another spoke of receiving a twenty-seven-year sentence for a crime he said he did not commit.

As DiDonato stood up and moved to the center of the circle, the men formed three groups—first tenors, second tenors, and baritones—each man holding a printed score. She addressed them by name; their mutual trust was evident. To begin, she led them through “He Will Gather Us Around,” a spiritual that opens the opera. Its tonalities are traditional, and her voice and theirs blended heartily.

A second piece, derived from the moment, described in the book, when Prejean first enters Angola and the guards announce her arrival on death row, was more challenging. As the men began to sing—“Woman on the tier! Woman on the tier!”—DiDonato listened intently. Then she gave an on-the-spot master class. “When you hit that first note, you don’t want to squash it like a bug, because then it’s dead. You want to hit it strong, so you can take it somewhere,” she said, and then demonstrated, her mezzo-soprano ringing out in the dingy hall.

The close harmonies in the piece are difficult even for professionals, and all the more so for amateurs whose practice time is limited. Between tries, DiDonato explained the tension in the piece: “For Sister Helen, it has the effect of, ‘I don’t know where I am here.’ It slopes down dissonantly, as if to say, ‘You don’t belong here, lady.’ And it’s the sound of the ‘death machine’ that is there in the prison all along.” Prejean said, “Wow, I never thought of that before.” Then she wryly praised the men for the effect that their singing about an episode from the beginning of her prison journey was having on her. “Y’all are making me afraid all over again,” she said.

After a third piece, the rehearsal concluded, and one of the men asked Prejean what he described as a “deep metaphysicall question”: “Sister Helen, how do we forgive ourselves? How do we move out of shame and guilt and into remorse?” In reply, she began to “talk regular,” inviting the group to consider that the word “forgive” breaks down into “for” and “give,” and that doing acts of love for others—acts of giving—allows one to get out of oneself and onto the path of forgiveness. It was an insight she had reached while in a prison, having got out of herself by befriending and then advocating for men condemned to death, and it was moving to hear her draw out this moral of her story in a setting where, in effect, that story began. ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.