“In solitary, they are trying to break you without realizing that most people in [prison] are there because someone else already tried to break them.” That’s how Paul Torres, a returning citizen who spent 90 days in solitary at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Los Angeles described his experience in solitary confinement to me last August.

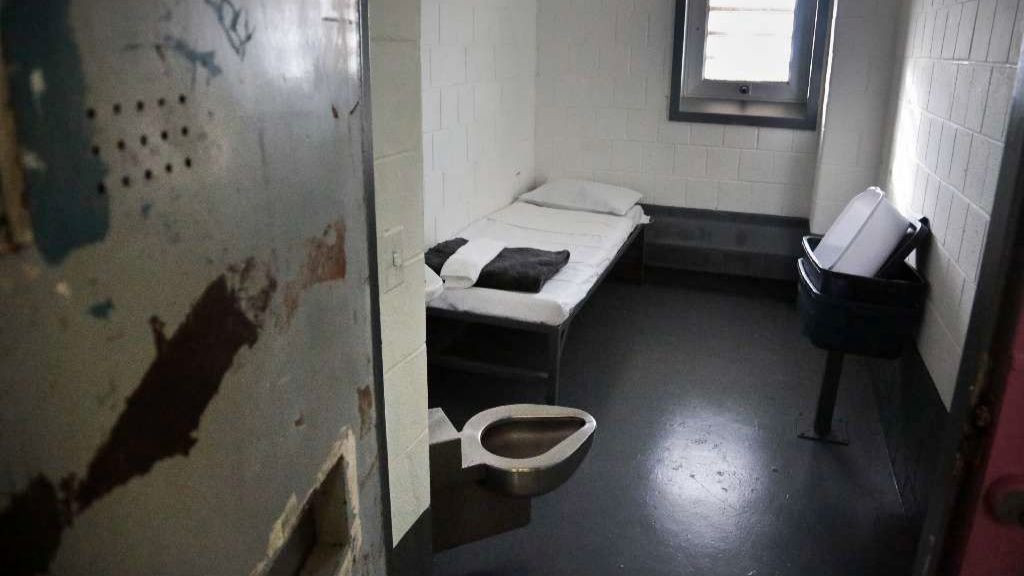

Paul was sent into solitary for not having his shirt on in his cell. It was a rule that wasn’t clear or fully enforced, and for that, he paid the price. Stuck in a tiny cell — about six paces across — with a concrete bed, window facing a blank wall, plastic mattress, one blanket, a towel, a small travel toothbrush, and no clock in sight, he said he felt stripped of his humanity.

As one of the cruelest forms of punishment, solitary confinement causes lasting mental and physical harm, yet the United States continues to use it as standard practice in its prisons. Last year, a report released by nonprofit watchdog Solitary Watch and the Unlock the Box Campaign to end solitary confinement indicated that 122,840 people were placed in solitary, also known as restrictive housing, in our prisons and jails. That’s about 6% of the total U.S. prison and jail population whose mental health and well-being were jeopardized.

To make matters even worse, recent reports show that while Black individuals only make up 38% of the Bureau of Prisons’ (BOP) population, they account for a disproportionate percentage — around 59% — of those placed in solitary, underscoring the systemic racism plaguing our criminal justice system.

As someone with over 25 years of experience working with the American Civil Liberties Union and the co-founder and co-chair of the Second Chance Task Force, I’m working in Congress to reform our criminal justice system. Bringing the inhumane conditions of solitary to light is a core component of that reform, which is why I’m proud to partner with Paul to drive real change.

For Paul, this is personal. When talking about his time in solitary, he says that it changed him. ” The isolation stripped me of my ability to interact appropriately with other people. When I was put back into the regular population, I felt threatened, overstimulated, and overwhelmed,” he said. “I hear keys, and I feel anxiety.”

I’ve always believed that our criminal justice system should be focused on rehabilitation, but what Paul and so many others like him have experienced is the polar opposite of rehabilitation: it’s torture.

Those placed in solitary are 15% more likely to be convicted of a future crime and often exhibit more violent behavior after release. One study even showed that people who had spent any time in solitary confinement were 24% more likely to die in the first year after their release from prison compared to those who had been incarcerated but not placed in solitary confinement.

We’ve seen study after study confirm that our prison system is long overdue for serious reform and come to the same conclusion: solitary confinement must be restricted. In fact, since 2014, two reports by the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office provided the BOP with 87 recommendations for how to reform solitary confinement, yet they’ve failed to implement 54 of them still to this day. That’s why I’m joining Paul in calling on the BOP to implement all 87 recommendations to ensure humane treatment in America’s prisons because we can and must do better.

After release, Paul became an Anti-Recidivism Coalition member and was given a real second chance. He says, “I was treated like the person I could be instead of like an animal. I was given resources to help me reenter. I felt valued and invested in. That feeling was everything. It changed the course of my life.” We need to start treating folks in prison that same way, and limiting the use of solitary confinement is an integral part of getting there. I hope you’ll join us this Second Chance Month as we work to reform solitary confinement and build a criminal justice system that is actually “just.”

U.S. Rep. David Trone (trone.house.gov/contact/) is the co-founder and co-chair of the Second Chance Task Force and the Bipartisan Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Task Force.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.