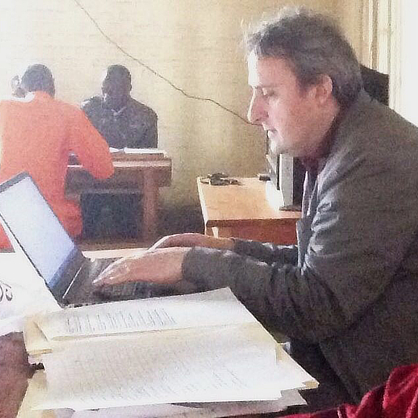

For Kevin Barnes-Ceeney, Ph.D., his research has brought him around the world and has taught him the power and importance of forgiveness. He’s bringing what he’s learned into the classroom and to his prestigious new role as the University’s Oskar Schindler Humanities Endowed Professor.

September 1, 2023

As a researcher and scholar, Kevin Barnes-Ceeney, Ph.D., has delved into some of the most heinous crimes that human beings have committed around the world, from the genocide in Rwanda to violence in the Caribbean. He wanted to understand how people might do – and be –better, and, ultimately, how individuals and communities might heal. In particular, he’s been focused on something that hasn’t typically had a prominent place in the field of criminal justice: forgiveness.

Dr. Barnes-Ceeney’s work has already impacted individuals and institutions around the globe, as well as his students at the University of New Haven. This academic year, he begins his three-year tenure as the Oskar Schindler Humanities Endowed Professor, one of the University’s most prestigious professorships. It will create opportunities for him to expand how he brings his work to students, both in and out of the classroom.

“This is a great opportunity to address topics that are central to my teaching and to my research,” said Dr. Barnes-Ceeney, an associate professor of criminal justice. “It is a very nice recognition of the work I’ve been putting in.”

‘We can’t force people to forgive’

Established nearly two decades ago upon the inauguration of Steven H. Kaplan, Ph.D., as president, the professorship enables educators to work with students on projects that are related to the encouragement of good human conduct and altruism. Dr. Barnes-Ceeney was chosen for the position by a committee that included previous Schindler Professors Marty O’Connor, M. Div, J.D., and David Schroeder, Ph.D.

Dr. Barnes-Ceeney says many scholars describe forgiveness as the “highest moral virtue,” yet even as a child, he noticed that forgiveness was often preached, yet not always practiced. The son of a prison chaplain, he would accompany his father to prison for services at Christmas. He soon became fascinated by how society viewed those who were incarcerated.

“Every world religion has forgiveness at its core, yet we don’t seem to have room for forgiveness in the way we think about people who perpetrate horrendous harm to other people,” he explains. “We can’t force people to forgive, though some countries have tried.”

‘Forgiveness itself can be quite freeing’

Those countries include Rwanda, where Dr. Barnes-Ceeney worked with individuals who were incarcerated following their direct involvement with the genocide in 1994. These were people who had committed horrific crimes – they’d attacked others with machetes, for example. There are still so many people imprisoned for their involvement in the genocide, says Dr. Barnes-Ceeney, that Rwanda continues to have one of the highest incarceration rates in the world.

As part of his research, Dr. Barnes-Ceeney visited three prisons in the African country – Muhanga, Ngoma, and Gasabo – where he conducted surveys to assess the incarcerated individuals’ physical and mental health needs and trauma. He wanted to determine what supports they needed as they left prison and reintegrated into the community. This transition, he knew, would be challenging, as many of their soon-to-be neighbors were those who had been directly impacted by their crimes. He also interviewed several dozen incarcerated perpetrators, and he found that even decades later, they were still deeply affected by the trauma they’d experienced during the genocide.

Dr. Barnes-Ceeney says this work has implications that extend far beyond the borders of Rwanda. Earlier this year, he presented his findings at the First International Conference on Forgiving and Being Forgiven, held in Israel.

“That really opened my eyes to this concept of forgiveness and how we’re missing ideas and notions of forgiveness in our current justice system,” he said. “Forgiveness itself can be quite freeing. We can let go of that hurt and that hate that can stay inside us and eat us up. Forgiveness is a way to move into a new phase of healing.”

‘Resilience rather than reactivity’

Dr. Barnes-Ceeney’s work has brought him around the world. He is continuing to conduct research in Jamaica to develop violence risk assessment and case management tools. Specifically, he’s been helping to develop a risk assessment tool to predict the risk of violence over two years in an effort to address Jamaica’s high rate of gun violence. He plans to continue to enhance the tool, which has already been used more than 11,000 times, and to collaborate with professionals in Jamaica.

Elsewhere in the Caribbean, Dr. Barnes-Ceeney has focused on juvenile justice system reforms in St. Lucia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Guyana. He’s worked with local officials to help end practices such corporal punishment and solitary confinement for children. Closer to home, he is working on a project in New Haven that explores inter-agency collaboration in an effort to lower rates of gun violence.

Dr. Barnes-Ceeney has endeavored to promote healing and prevent violence throughout the United States as well. Since 2015, he has offered Social Resilience Model Training, an approach that draws on neuroscience. The training has been offered to a variety of professionals, including police officers, educators, and clergy, in locations such as Boston, Mass., and Dayton, Ohio. He describes the program as similar to mindfulness.

“It teaches people to be aware of what’s going on in their bodies so they can control and bring in the parasympathetic nervous system,” he said. “This way, they can approach stressful situations from a place of resilience rather than reactivity.”

‘A good opportunity to explore this’

Dr. Barnes-Ceeney’s impactful work as a researcher informs his role as professor. A dedicated mentor, he frequently includes students in his research. He currently has half a dozen doctorate students starting independent research projects under his mentorship, and he also works closely with undergraduate students.

A committed educator, Dr. Barnes-Ceeney is known for developing challenging and thought-provoking courses. As part of his immensely popular “Pimps, Pushers, and Perverts” course, students read autobiographies written by formerly incarcerated people. They explore pathways into and out of offending, learn about how people have turned their lives around, and consider treatment and rehabilitation options.

“Administrative Evil,” an Honors course Dr. Barnes-Ceeney teaches, enables students to explore how “ordinary people doing their jobs well” have contributed to immense suffering. With a focus on the Holocaust, it also includes current events in the U.S., such as the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

The Schindler Professorship will enable Dr. Barnes-Ceeney to expand the courses he teaches at the University. This spring, he will teach an “After Violence” course for the first time, which will dovetail on his research. The course, which will explore how individuals, communities, and countries heal after violence, will also challenge students to focus on forgiveness in their own lives. They will work through a multistep forgiveness program and reexamine the role of forgiveness in their own lives.

“They don’t necessarily have to address something in their lives that, for them, is a 10, but they can focus on something they’d consider to be a two or a three,” he explains. “They can see how far they get in the process toward letting go of something that they’ve been holding onto. This is still fairly new in the field, and it’s a good opportunity to explore this with students.”

‘It’s about trying to understand and help people’

Passionate about bringing his work to students beyond the classroom, Dr. Barnes-Ceeney hopes his professorship gives him the opportunity to embed an element of forgiveness programming in the student conduct process.

Dr. Barnes-Ceeney has been a member of the University’s Student Conduct Board for three years now, and he hopes including an element of forgiveness will help ensure healing on campus. It’s something that, he believes, will benefit not just the University community, but all communities.

“It’s about people talking to and listening to each other, as well as developing empathy for each other,” he explains. “It’s about trying to understand and help people, rather than just trying to be punitive and ‘catching’ people.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.