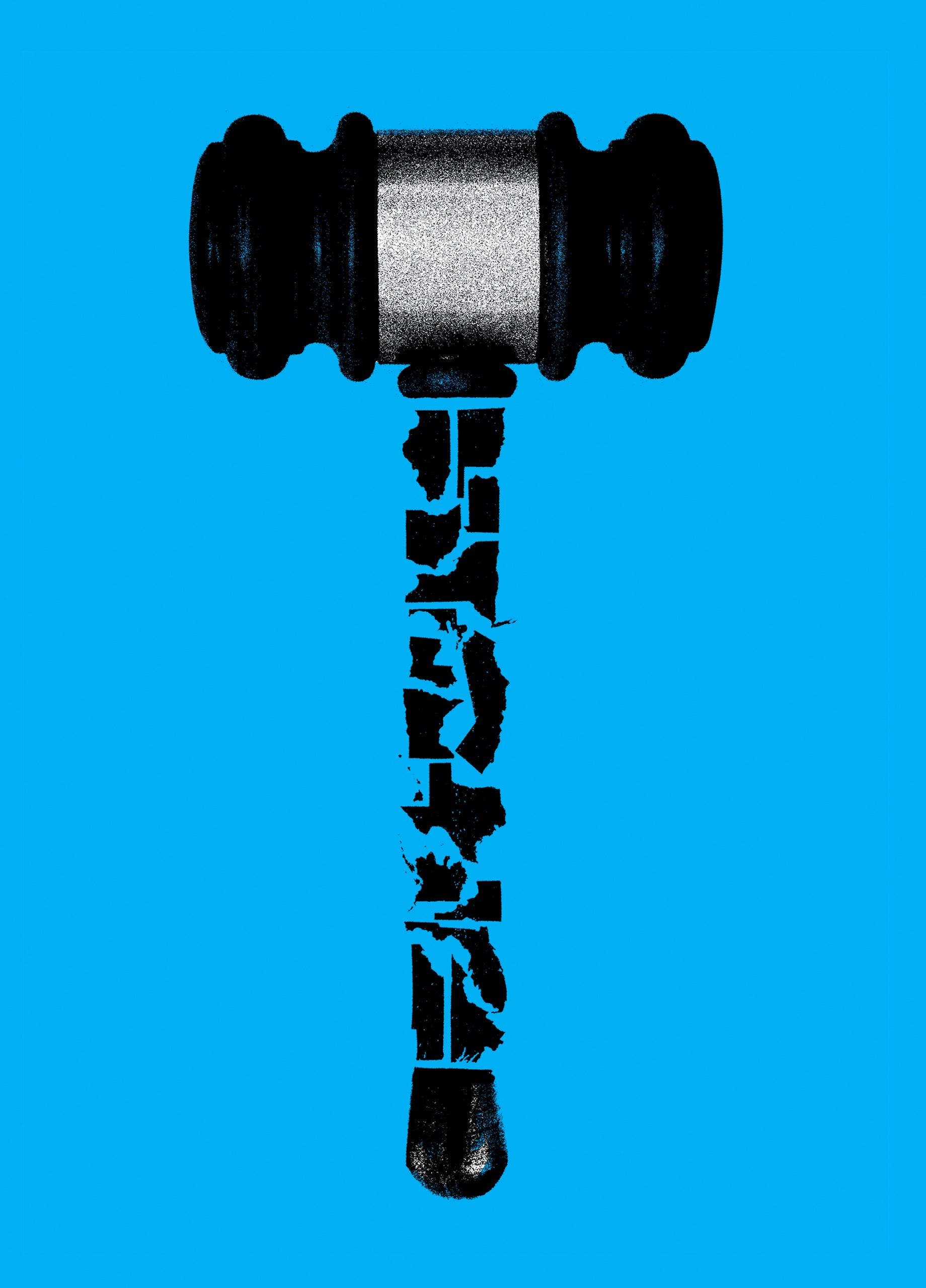

Can State Supreme Courts Preserve—or Expand—Rights?

In November, 2020, Lauren McLane, a professor at the University of Wyoming College of Law, was forwarded a letter from Christopher Hicks, an incarcerated man who’d been sentenced to life without parole for his role in a murder. The letter was part of a petition, prepared by Hicks, laying out “all the pertinent information, charges and reasons” that he deserved consideration for a pardon. The murder, he wrote, had been carried out fifteen years earlier by another man, who entered the victim’s house while Hicks remained in the back seat of a car, intoxicated. Noting that he was a teen-ager at the time, Hicks claimed that he’d been pressured into participating in the crime by a third, older man, who lived in the trailer where Hicks had been residing.

McLane runs a clinic that regularly helps indigent clients in Wyoming file motions to reduce their sentences. Yet, when she finished Hicks’s petition, she said to herself, “This is an absolute lost cause.” In part, she felt this way because of the notorious reputation of Kent Proffit, Sr., the older man who’d orchestrated the murder: Proffit, an alleged child molester, had wanted to prevent the victim, a sixteen-year-old boy, from testifying against him in a sexual-assault trial. Another problem was that Hicks had been nineteen when the crime occurred. In a 2012 Supreme Court case, Miller v. Alabama, the Justices had barred judges from sentencing juveniles to mandatory life without parole, on the ground that doing so violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Justice Elena Kagan, who wrote the majority opinion, argued that children’s “diminished culpability and heightened capacity for change” required judges to consider their age when determining their punishments. But, as McLane knew, the Miller decision applied only to defendants who were younger than eighteen when they’d committed crimes. Because Hicks had been a little older than this, McLane assumed that no judge would deem his age a mitigating factor.

A few months later, however, she learned about a case that made her reconsider. The case, In re Monschke, came before the Supreme Court of Washington State, which, in a 4–3 decision, ruled that Miller should be extended to two petitioners who’d committed homicides when they were nineteen and twenty years old, respectively. The justices noted the prohibition on “cruel punishment” in Washington’s state constitution, and cited neuroscientific research, presented in court, showing that the brains of young adults were still developing, leaving them susceptible to the same impulsive behavior as juveniles.

One lawyer involved in the Monschke case was Jeffrey Ellis, who taught a seminar on capital punishment that McLane had taken in law school, at Seattle University. She began to wonder whether a similar case might be brought in her home state. McLane recognized the vast differences between the political climates of Washington, which had one of the most liberal supreme courts in the country, and Wyoming, where Donald Trump won nearly seventy per cent of the vote in 2020. But she also knew that Wyoming, like much of the rest of the Mountain West, prided itself on not taking directives from the federal government.

McLane combed through recent Eighth Amendment cases that had come before the Wyoming Supreme Court and spotted evidence of this independent spirit. In a 2014 case, Bear Cloud v. State, the justices noted that the plaintiff, who sought an itemized sentencing hearing for an aggregate punishment he’d been given for a series of crimes committed when he was sixteen, had made “no more than a passing reference to the protections that might be afforded by our state constitution.” They added, “Our state constitution need not necessarily be analyzed by ‘blindly follow[ing] the United States Supreme Court’s interpretation.’ ”

Wyoming’s constitution, like those of several other states, contains an analogue to the Eighth Amendment that prohibits cruel or unusual punishment—a minor but potentially important textual difference. After weighing these factors, McLane called Christopher Hicks. She mentioned the Monschke decision and said, “I think this is something we can do.”

In 1976, Justice William Brennan delivered a speech at the annual convention of the New Jersey State Bar Association. In the previous two decades, Brennan, who had served on the New Jersey Supreme Court for five years before Dwight Eisenhower appointed him to the U.S. Supreme Court, had written, or joined, dozens of influential opinions that broadened the rights of criminal defendants, women, Black people, and indigent Americans. Many of these decisions invalidated state laws that sanctioned racial discrimination, by augmenting the authority of the federal government. But Brennan, in his speech, endorsed an idea that seemed to move in the opposite direction, making an impassioned case for state courts to issue rulings that pushed beyond protections enshrined in federal law. “State courts cannot rest when they have afforded their citizens the full protections of the federal Constitution,” he said. “State constitutions, too, are a font of individual liberties, their protections often extending beyond those required by the Supreme Court’s interpretation of federal law.”

As Brennan peered around the ballroom where the conventioneers were gathered, he saw the crowd thinning, and became convinced that his speech was flopping—so much so that he walked offstage before finishing it. But, the following year, his full address was published in the Harvard Law Review, and it became one of the most widely cited law-review articles ever written, inspiring what legal scholars have called “the new judicial federalism”—a movement in which state courts, citing provisions in their own constitutions, issued a flurry of decisions widening the scope of rights. Among them was State v. Novembrino, a 1987 case in which the New Jersey Supreme Court endorsed protections against unreasonable searches and seizures that were more robust than those in federal law, siding with a suspect who had been charged with possession of illegal drugs on the basis of evidence obtained through a nonconsensual search. (The decision rejected the “good-faith exception” endorsed by the Supreme Court, which critics have argued gives the police too much latitude to engage in misconduct.) Although the Constitution’s supremacy clause forbids states from violating federal rights, nothing bars them from amplifying those rights. In the decade after Brennan’s article appeared, state courts handed down more than two hundred such rulings, on issues ranging from free speech to the death penalty—a tenfold increase from the previous ten years.

Brennan’s article had a major impact because of his stature, and because, by the late seventies, the Supreme Court was no longer engaged in the expansion of rights that had unfolded under Chief Justice Earl Warren, who retired in 1969. The subsequent appointment of four Justices who were nominated by Richard Nixon—including Warren Burger, who succeeded Warren as Chief Justice—had left Brennan increasingly isolated and dismayed, a feeling that he didn’t hide in his speech. The Supreme Court was failing to protect rights, he complained, including in cases involving the equal-protection clause—a retreat that “constitutes a clear call to state courts to step into the breach.”

As necessary as such interventions may have seemed to Brennan nearly half a century ago, a growing number of advocates and legal scholars believe that they are far more urgent today. In February, I heard this view expressed repeatedly at a two-day symposium on state constitutions held at New York University School of Law and organized by the Brennan Center for Justice. (The center is named for Brennan himself.) A decade ago, a conference on such a subject likely would have been a modest gathering. This year, the turnout was so heavy that many attendees had to sit outside the main room and watch the proceedings on a simulcast.

“Justice Brennan’s call to action has never been more salient,” Michael Waldman, the president of the Brennan Center, declared in the opening address. If the symposium owed a debt to Brennan, it owed no less of one to Senator Mitch McConnell and to President Trump, who helped to entrench a lopsided 6–3 conservative majority on the Supreme Court. Recent Court rulings—from Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade, to Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency, which weakened the Clean Water Act—have left many progressive analysts convinced that, for at least a generation, trying to expand federal rights will be a hopeless cause. (A notable exception is the rights of gun owners, toward whom the Justices have been solicitous.) State litigation offers far more opportunities, the speakers at the symposium affirmed. Forty-nine states “have stronger protections for voting rights than the U.S. Constitution does,” Waldman noted in his address. State constitutions are also much easier to change: whereas a federal constitutional amendment must be ratified by three-quarters of state legislatures, a process that can take decades, amending the constitutions of most states requires a single referendum. For this reason, pro-choice advocates in numerous states have lately pushed to place amendments legalizing abortion on the ballot. (So far, four states have amended their constitutions to protect abortion rights, and in November there could be referendums on the matter in as many as fourteen states.)

In Dobbs, the Supreme Court left it to states to fashion their own laws and policies on abortion. Fourteen states have bans in effect which criminalize the procedure in nearly all circumstances. But the high courts of eleven others have recognized that their constitutions protect abortion rights independently from the federal Constitution. Some states have also framed abortion access in novel ways—for example, as a matter of equality rather than privacy, an argument that many feminist scholars have long considered superior. Shortly before the N.Y.U. symposium, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled that a state ban on Medicaid coverage for abortion was “presumptively unconstitutional” because it violated both the Equal Rights Amendment, which Pennsylvania has ratified, and the equal-protection clause in the state’s constitution. At the symposium, Mary Ziegler, a legal historian, speculated that, in fifty years, when scholars write the story of Dobbs’s reversal, “many of the early chapters are going to be about what occurs in state courts.”

One criticism of the call for state courts to play a more prominent role in protecting rights is that the underlying motive is ideological; in Brennan’s case, he was openly trying to counter the Burger Court’s rightward shift. At the N.Y.U. symposium, Goodwin Liu, a justice of the Supreme Court of California and a strong proponent of judicial federalism, said that such concerns were likely why many of his peers “look a little bit askance at this project,” dismissing it as an attempt to preserve only liberal rights.

But not everyone who is sympathetic to judicial federalism leans left. At the symposium, Clint Bolick, a self-described “textualist” who served in the Reagan Administration and is now a justice of the Arizona Supreme Court, said, of state jurists, “U.S. Supreme Court Justices do not take oaths to the state constitution, but we do.” In Bolick’s view, state courts that reflexively follow the Supreme Court are shirking their duty to protect the rights enshrined in their own constitutions.

The best-known recent book on state-constitutional law is “51 Imperfect Solutions,” by Jeffrey S. Sutton, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and a former clerk for Justice Antonin Scalia. Sutton writes, “For too long, we have lived in a top-down constitutional world, in which the U.S. Supreme Court announces a ruling, and the state supreme courts move in lockstep in construing the counterpart guarantees of their own constitutions.” In a diverse democracy, Sutton argues, it is preferable for state courts to exercise independence, spurring the kind of experimentation that America’s federalist system was designed to cultivate. Because state courts preside over smaller jurisdictions, he notes, they can craft remedies without imposing a one-size-fits-all rule on the entire country. One example that Sutton cites is San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, a 1973 case in which the Supreme Court ruled that inequalities in Texas’s public-education system did not violate the Constitution. (The lawsuit was brought by a parents’ association in an underfunded school district.) In response, numerous lawsuits were filed in state courts, many of them invoking the right to a public education—something that all state constitutions explicitly affirm. In 1989, the Texas Supreme Court ordered officials to create a more equitable system, citing the state constitution’s guarantee that the “general diffusion of knowledge” will be fostered. By 2004, the school district in the Rodriguez case was spending more per pupil than Alamo Heights, an affluent neighborhood that the plaintiffs had highlighted in their original lawsuit.

A skeptic might note that granting states more leeway to work out constitutional questions has sometimes had pernicious effects, particularly in the Jim Crow South. Sutton acknowledges this, but argues that the dynamic has changed. On many issues, he writes, “the state courts in recent years have gone from being civil-rights followers to leaders.”

This shift has been especially evident with gay rights. I recently spoke with Mary Bonauto, the senior director of civil-rights and legal strategies at G.L.B.T.Q. Legal Advocates & Defenders (glad). In 1997, glad, along with two Vermont lawyers, filed a lawsuit on behalf of three same-sex couples in the state who’d been denied marriage licenses. Same-sex marriage was then illegal throughout the United States. Bonauto drew inspiration from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s formulation, in 1996, that “the history of our Constitution . . . is the story of the extension of constitutional rights and protections to people once ignored or excluded.” Bonauto was also motivated by a personal longing, she told me—the desire to marry the woman she loved.

The case was brought in Vermont’s state-court system, Bonauto said, in part because in the U.S. marriage is regulated by state law. But the choice of venue was also strategic. She and her co-counsellors didn’t want to file a federal case that might eventually come before the Supreme Court, knowing that it could issue a decision that would set back their cause. In 1986, the Justices had ruled, in Bowers v. Hardwick, that a Georgia law criminalizing sodomy did not violate the Constitution. A decade earlier, it had dismissed an appeal from two men in Minnesota who’d been denied the right to marry; the Court rejected their petition “for want of a substantial federal question.” Bonauto told me, “I don’t think any of us who were working on this wanted to have premature Supreme Court review, because we were very confident that we would lose.”

Given that states have the final say when interpreting their own constitutions, glad’s lawsuit in Vermont—one of the first states to pass a nondiscrimination law protecting gays and lesbians—avoided the risk of federal intervention. In 1999, the Vermont Supreme Court, citing a clause in the state constitution that prohibits bestowing favoritism on any particular “set of persons,” ruled that same-sex couples were entitled to “the same benefits and protections” afforded to married couples. Bonauto was thrilled, even though the decision left the remedy to the legislature, which passed a civil-union law instead of legalizing same-sex marriage.

glad soon filed a similar lawsuit in Massachusetts, on behalf of seven same-sex couples. In 2003, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled in the plaintiffs’ favor. The decision cited the Massachusetts constitution, particularly its Declaration of Rights, which the justices pointedly described as “more protective of individual liberty and equality than the Federal Constitution.” Same-sex couples started getting married in Massachusetts more than a decade before the Supreme Court eventually ruled, in Obergefell v. Hodges, that all Americans had the right to do so.

The triumph of marriage equality might seem inevitable today. Bonauto doesn’t see it that way, recalling how much fear pervaded the L.G.B.T.Q. community when the first cases were filed. “I find it hard to imagine that we would be where we are today without Vermont and Massachusetts,” she told me. By the time the Obergefell decision was issued, in 2015, popular attitudes had shifted, she acknowledged. The U.S. Supreme Court acted as a “consensus confirmer,” she said. But state courts, with their freedom to experiment, had helped to bring about that social change. “They can have a catalytic effect,” she told me.

Between sessions at the N.Y.U. symposium, I went to a café to meet Kyle Barry, an advocate who hopes that a similar pattern might play out in the movement for criminal-justice reform. Barry came to the conference from San Francisco, where he directs the State Law Research Initiative, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to limit extreme sentences and address inhumane prison conditions by strengthening state-constitutional rights. Criminal-justice scholars have traditionally framed mass incarceration as a national phenomenon driven by such harsh federal legislation as the 1994 crime bill. But, as the authors of a recent Iowa Law Review article note, “ninety percent of people confined in U.S. prisons are confined under state laws.” Given this, the authors ask why state courts have been “missing from the debate” about how to curb excessive punishment regimes.

Barry’s organization hopes to address this gap. He told me that state litigation was especially urgent because the Supreme Court has “completely abdicated” enforcing constitutional rights in the criminal-justice system, rubber-stamping extreme sentences that many other countries prohibit. In most of Europe, he noted, the sentence of life without parole is unheard of. In 2022, Canada’s Supreme Court ruled unanimously that such sentences were cruel and unconstitutional for offenders of any age. In the U.S., as of 2020, sixty thousand people were serving what Barry calls “death in prison” sentences—more than in the rest of the world combined. Although the Miller ruling forbade mandatory impositions of life without parole for juveniles, it didn’t ban them altogether. And a more recent Supreme Court opinion, Jones v. Mississippi, written by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, relieved judges of having to establish that a juvenile is “permanently incorrigible” before issuing such a sentence.

In a scathing op-ed in the Washington Post, the legal scholar John Pfaff argued that the Jones ruling demonstrated that America was willing “to throw lives away.” Yet Barry told me that he felt optimistic about the possibilities for state reform, naming Michigan, in addition to Washington, as a place where a high court had recently extended Miller to young adults. Lauren McLane, the law professor fighting to reduce the sentence of Christopher Hicks, joined us at the café, dressed in a gray University of Wyoming sweatshirt. McLane and Barry had first communicated a few weeks earlier, after she’d read comments that he’d made on a Listserv about Commonwealth v. Mattis, a case in which the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts banned life without parole for “emerging adults”—defined as anyone between eighteen and twenty-one. The ruling, which was made in January, cited the ban on “cruel or unusual punishment” in the Massachusetts constitution, and also the principle that Eighth Amendment jurisprudence should be informed by “the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society”—a standard that the U.S. Supreme Court itself has endorsed.

McLane informed Barry of her plans to file a lawsuit challenging mandatory life without parole for young adults in Wyoming. She discussed Hicks’s case, and talked about how she’d got to know him, learning more about his teen-age years—he’d endured extensive abuse—and about his determination to make amends for what he’d done. (At the Wyoming State Penitentiary, Hicks helped to run a mentoring program for incarcerated youth.) McLane acknowledged that, in a conservative state like Wyoming, the odds of securing a new sentencing hearing for Hicks might be long. But, she said, “I’ve been telling my students, ‘If we can do this here, we can do it anywhere.’ ”

McLane wanted her lawsuit to highlight the commitment to reform that permeates Wyoming’s constitution, something its high court had alluded to in several rulings she’d come across. A core tenet of judicial federalism is that state constitutions contain provisions reflecting states’ distinctive values and history. In Wyoming, Article 1, Section 15, says, “The penal code shall be framed on the humane principles of reformation and prevention.” McLane planned to cite this language in her lawsuit. She also intended to quote an 1898 ruling by the Wyoming Supreme Court which declared that “the modern prison system, at every stage of its evolution, revolves around one central thought—the possibility of reformation. . . . The reformation of the prisoner is its one animating purpose.”

McLane told me, “I’ll be submitting a motion to challenge Chris’s sentence this summer, and I am hopeful that he and other similarly situated young adults in Wyoming will be granted the same grace, dignity, and justice that those emerging adults in states like Washington and Massachusetts have been extended.”

Any excitement at the N.Y.U. symposium was qualified by an acknowledgment that a victory in a state supreme court has much more limited effects than winning a U.S. Supreme Court case. It’s “a second-best alternative,” Robert Williams, the director of the Center for State Constitutional Studies, at Rutgers, said on one panel. The Mattis ruling underscored this: the decision made more than two hundred incarcerated people in Massachusetts serving life-without-parole sentences eligible for new hearings, but it did nothing for the tens of thousands of people serving similar sentences outside the state.

Williams has been writing about state-constitutional law since 1980. In 2000, Bonauto sought his guidance about the Massachusetts lawsuit that glad filed, for which he submitted an amicus brief. As a distinguished figure in a marginalized specialty, he is delighted that his area of expertise is finally generating wider interest. One indication of this change is the A.C.L.U.’s decision, a year ago, to launch a State Supreme Court Initiative. Among the effort’s leaders is Matthew Segal, a senior staff attorney at the organization. Segal was given the job in part because he’d had a string of successes with civil-rights cases while serving as the legal director of the A.C.L.U. of Massachusetts. In 2020, he secured the release of five thousand people from state prisons and jails because of health risks related to covid-19. He was the lead A.C.L.U. counsel in two cases that ended with more than sixty thousand drug charges being overturned on the ground that state-run labs had engaged in misconduct and relied on fabricated evidence. According to the A.C.L.U., this is the largest dismissal of wrongful convictions in U.S. history. These victories stood in stark contrast to Segal’s experiences in federal court, which, he told me, had often been frustrating. In 2017, for example, a federal judge declined to extend a temporary restraining order that Segal and several colleagues had obtained to block Trump’s travel ban, which excluded people from seven majority-Muslim countries from entering the U.S. (The Supreme Court later upheld a revised version of the ban.) When the opportunity to run the State Supreme Court Initiative arose, Segal immediately said yes. In the past thirteen months, the project has filed amicus briefs or served as co-counsel in twenty-five cases in eighteen states, on issues ranging from abortion to election reform.

Segal attended Yale Law School, where, he said, he received little training for such work. “The focus at a lot of law schools that are highly regarded has been federal law,” he said. “There’s been no real teaching in state-constitutional law.” But, last fall, Yale did offer a seminar on the subject—one that Segal co-taught with Julie Murray, another senior A.C.L.U. attorney. Segal told me that he saw the class as a complement to his advocacy work—he is now teaching a similar course at Tufts—and that he hoped to get the next generation of activist lawyers to rethink their priorities. “If there are going to be advances in civil rights and civil liberties in the near term—and maybe even the medium and long terms—they’ll have to come from state courts,” he said.

One Yale student in the seminar was Pragya Malik. The previous year, she’d taken two classes that reflected her passion for social justice: “Litigating Civil Rights, Policing, and Imprisonment,” and “Law and Inequality.” The courses left her deflated, she said, in part because they focussed on federal law, where the barriers to effecting change seemed so daunting. “You’re jumping through all these hoops,” she said. Malik learned that, in addition to the obstacles posed by the Supreme Court’s conservative super-majority, there were legal hurdles such as qualified immunity, which shields law-enforcement officials from liability for abuses unless a violation of specific civil rights is “clearly established.”

Last summer, Malik worked at a public-defender service in Washington, D.C., where she overheard a peer talking about a mass-exoneration case in Massachusetts. She consulted the A.C.L.U.’s Web site to learn more, and saw that the leading force behind the suit, Segal, would be teaching a course at Yale that fall. She signed up. After taking the seminar, she came away excited about the power that lawyers could have to “affect people’s lives” through state courts. Segal told me that, in his class, he emphasizes that state supreme courts, far more than federal courts, viewed themselves as “problem solvers.” The wrongful-conviction cases that he’d litigated came about when the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts invoked its “superintendence authority” over lower courts where tainted evidence had been used, forcing the state to clear thousands of people’s records and enabling the victims to recover millions of dollars in fines and fees. Federal courts also possess this authority, but rarely exercise it. Segal said, “The world of state courts allows for more creativity and inventiveness than you see in federal court.”

One potential barrier to litigating civil-rights cases in state courts is that, unlike at the federal level, lawyers are generally not entitled to recover attorneys’ fees if they win. At the N.Y.U. symposium, Julie Murray, of the A.C.L.U., recalled that, when she was employed at another nonprofit, she worked on a civil-rights lawsuit in Iowa that dragged on for more than a year. The organization won in trial court, but recouped only three hundred dollars in costs.

James A. Gardner, a professor of law at the University at Buffalo who has written extensively about judicial federalism, has raised other caveats. He is skeptical that state courts can spearhead a meaningful expansion of rights, because of heightened partisanship and “the politicization of constitutional law,” which has eroded the independence of state courts, particularly where Republicans wield power. As Gardner documents in a forthcoming law-review article, in recent years Republicans in places such as Georgia have packed state supreme courts to insure rulings favorable to their agenda. In 2017, Georgia’s Supreme Court expanded from seven justices to nine.

Judges in Republican-controlled states who have made expansive rulings in favor of rights have also been attacked politically, and even threatened with impeachment. For judicial federalism to flourish, “state judiciaries must enjoy genuine independence from transitory political winds,” Gardner argues. “Judges who are tethered tightly to trends in state and national politics, and thus fearful of partisan retaliation for decisions they make, are unlikely to enjoy the independence necessary to forge a state constitutional jurisprudence of any organic distinctiveness.”

State courts are significantly less insulated from political pressure than their federal counterparts. In 2022, the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down a voter-I.D. law that it concluded was racially discriminatory. The next year, the decision was reversed—after Republicans elected two new conservatives to the bench. This shift in the balance of power occurred after Republicans in the state legislature eliminated public funding for appellate judicial elections and changed the law so that party labels could be affixed to candidates. Douglas Keith, a scholar who tracks the role of dark money in judicial campaigns, told me that before these changes judicial elections in North Carolina had been quiet, nonpartisan affairs. They have now become hyperpartisan battles in which candidates bankrolled by the Republican State Leadership Committee—the nation’s largest spender on state-supreme-court elections—have largely prevailed.

A related trend in American politics is politicians’ declining commitment to democracy itself. The journalist Ari Berman, in a new book, “Minority Rule,” examines how tactics such as voter suppression and gerrymandering have undermined the popular will. The Supreme Court has not seemed terribly troubled by this, issuing rulings that have weakened voting rights and, in May, determining that Republicans in South Carolina did not unlawfully consider race when they drew a congressional district in a way that removed thirty thousand Black voters, overriding a lower court that had ordered legislators to redraw the district. A case can be made that the U.S. Constitution was designed to sustain minority rule, protecting white male property owners from the so-called tyranny of the majority. Indeed, as Berman points out, the current Supreme Court is itself a product of minority rule: five of the six conservative Justices—including Samuel Alito, who wrote the majority opinion in the South Carolina case—were appointed by Presidents who had assumed office after losing the popular vote.

State constitutions offer a potential counterweight to these trends. They embody what the law professors Miriam Seifter and Jessica Bulman-Pozen have termed “the democracy principle”—a commitment to popular sovereignty that is reflected in language vesting power in the people and in explicit assurances of the right to vote. Seifter co-directs the State Democracy Research Initiative, at the University of Wisconsin Law School, in Madison, which she launched, in 2021, with her husband, Robert Yablon, a professor who specializes in election law. One of their goals is to advance research and dialogue about state courts, thereby strengthening democracy. In Seifter’s state, progressives recently scored a major victory in this arena. Starting in 2011, creatively designed legislative maps enabled Republicans to retain power in the state legislature even after losing the popular vote. Janet Protasiewicz, a circuit-court judge, decried these maps, calling them “rigged.” Her outspokenness on the issue helped her to win election to the state supreme court in 2023. Republicans threatened to impeach Protasiewicz unless she agreed to recuse herself from any cases involving the maps, but the effort failed, and a case challenging partisan gerrymandering soon came before the justices. In December, they ruled that more than half of the legislative districts in Wisconsin violated a provision of the constitution requiring them to be composed of “contiguous territory,” and ordered that new maps be drawn.

Another state in which the “democracy principle” has been tested is Montana, where, in 2021, a coalition of Native American tribes challenged voting restrictions, including the elimination of Election Day registration, which they claimed had a disproportionate impact on them. In recent years, federal courts have rarely taken exception to such measures, applying strict scrutiny only to a law that “severely burdens” the right to vote. In an amicus brief, ten constitutional-law scholars, among them Miriam Seifter and Robert Williams, argued that upholding the voting restrictions would “erase Montana’s distinctive constitutional language, structure, and tradition,” all of which warranted a more exacting standard. (The Montana constitution mandates that all elections “be free and open,” and that no power “shall at any time interfere to prevent the free exercise of the right of suffrage.”) In March, the Montana Supreme Court struck down the restrictions, and warned that it would view skeptically any state law that “impermissibly interferes” with the right to vote.

Not only do state constitutions generally express a stronger commitment to democracy than the U.S. Constitution does; they enumerate many rights and protections that have no federal analogue. In several states, for example, a person in custody cannot be treated with “unnecessary rigor.” I discussed this concept recently with Daniel Greenfield, who helps to run the Prisoners’ Rights Clinic at U.C.L.A. Last year, Greenfield petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case of Michael Johnson, a mentally ill man in Illinois who’d been caged in a filthy solitary-confinement cell for nearly three years, without access to exercise or fresh air. The Court denied the petition, overriding a strong dissent from Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who noted the “unusually severe” conditions that he’d endured. The decision, Greenfield told me, left him “with the unshakable feeling that it was time to turn to state courts and state constitutions.” He’s now working with law students to identify state courts where incarcerated clients can get relief. One of the places they are eying is Oregon, whose constitution has an “unnecessary rigor” clause, which has recently been invoked to hold prison officials accountable for inhumane conditions.

Many state constitutions also affirm positive rights absent from the U.S. Constitution, including a right to “social welfare,” which New York recognizes, and a right to grow and harvest food, which was incorporated into Maine’s constitution in 2021, after voters approved an amendment, propelled by concerns about the growing power of agribusiness. The amendment asserts that individuals have the right to “produce and consume the food of their own choosing.” Some scholars contend that the mutability of state constitutions is a flaw. But the comparative ease of amending them also means that many of their provisions “are quite recent, and often reflect contemporary concerns,” Alicia Bannon, a scholar at the Brennan Center who edits State Court Report, a new online publication that tracks state-constitutional developments across the country, told me.

Among the contemporary concerns that state courts have begun addressing is climate change. Held v. Montana, a lawsuit filed in 2020, invokes an inalienable right to “a clean and healthful environment.” This phrase doesn’t appear in the U.S. Constitution, of course, but it’s enshrined in Montana’s constitution, which was rewritten in 1972—two years after the first Earth Day took place. When the Held lawsuit was filed, the plaintiffs ranged in age from two to eighteen, reflecting the fact that, as the complaint noted, “children are uniquely vulnerable to the consequences of the climate crisis.” Among those named in the lawsuit are Rikki Held, who grew up on a ranch that has recently been ravaged by floods and wildfires, which have threatened her family’s livelihood, and Olivia Vesovich, a teen-ager who has repeatedly had to leave the state in the summer because smoke-filled air exacerbated her asthma. The complaint quotes the preamble of Montana’s constitution, which celebrates “the quiet beauty of our state, the grandeur of our mountains, the vastness of our rolling plains . . . for this and future generations.”

Our Children’s Trust, a nonprofit public-interest law firm, filed the case. It also litigates in federal court, and in 2015 it submitted a complaint in U.S. District Court on behalf of young people in Oregon. For years, that case stalled as the U.S. Department of Justice filed motion after motion to delay it. The tactic felt particularly egregious, Andrea Rodgers, a lawyer with Our Children’s Trust, told me, because mitigating climate change requires immediate action. In May, a U.S. circuit court of appeals finally weighed in on the case and, to the dismay of the plaintiffs, dismissed it. “I have been pleading for my government to hear our case since I was ten years old, and I am now nearly nineteen,” one of the plaintiffs said. “A functioning democracy would not make a child beg for their rights to be protected in the courts, just to be ignored.”

In Held v. Montana, a very different scenario played out. There were few delays in the case, and last year it went to trial, enabling Held and her fellow-petitioners to testify. A state district court ruled that their rights had been violated. Addressing the plaintiffs’ injuries imposes “an affirmative duty upon their government to take active steps,” the district court declared, striking down a Montana provision that had allowed state agencies to ignore greenhouse-gas emissions when approving energy projects. State officials immediately appealed to the Montana Supreme Court, which, in January, declined to stay judgment in the case. Oral arguments are scheduled to begin in Helena on July 10th.

Our Children’s Trust has since filed another lawsuit challenging inaction on climate change, in Hawaii; the case will go to trial in June. Like Montana, Hawaii recognizes the right to a clean and healthful environment in its constitution. If the Hawaii Supreme Court ends up invoking this provision, it will not mark the first such occasion. Last year, the court ruled unanimously that a state agency had the power to block an energy company from building a tree-burning facility on the Big Island which, in three decades, would have emitted eight million tons of carbon dioxide. In a concurring opinion, Justice Michael Wilson observed that Hawaii was “constitutionally mandated” to address the climate crisis because it was a “sui generis” emergency. (Deadly wildfires engulfed a town on Maui last summer, killing a hundred and one people.) Addressing global warming was also necessary because of the “stark failure of the federal judiciary to grant redress to present and future generations alleging knowing destruction of a life-sustaining climate system,” he went on. Among the examples he cited was West Virginia v. E.P.A., a 6–3 decision, issued in 2022, in which the Supreme Court curtailed the agency’s latitude to regulate greenhouse-gas emissions. The federal courts were abdicating their responsibility “to leave future generations a habitable planet,” Justice Wilson wrote. Unlike those courts, “the Hawai‘i Supreme Court does not choose to ‘throw up our hands.’ ” ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.