This Black History Month, Peoples Dispatch is exploring the history of the notorious Louisiana State Penitentiary, the site of centuries of Black struggle—first against slavery, then convict leasing, and now the US prison system, which some label as slavery in the modern day.

At the helm of the US’s notorious system of mass incarceration sits Louisiana State Penitentiary. Apart from being the largest maximum-security prison in the United States, this prison, nicknamed “Angola” after the former plantation site that it sits on, is an example of the conditions of modern-day slavery that the US prison system inflicts upon its disproportionately Black incarcerated population.

The Angola Plantation

Before the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, the land the prison currently sits on was known as the Angola Plantations, owned by slave trader Isaac Franklin. The name “Angola” comes from the southern African nation, with another one of Franklin’s plantations being named “Loango” after the pre-colonial African kingdom. Angola became one of the most productive plantations in the US South, churning out 3,100 bales of cotton per year via the labor of its slaves.

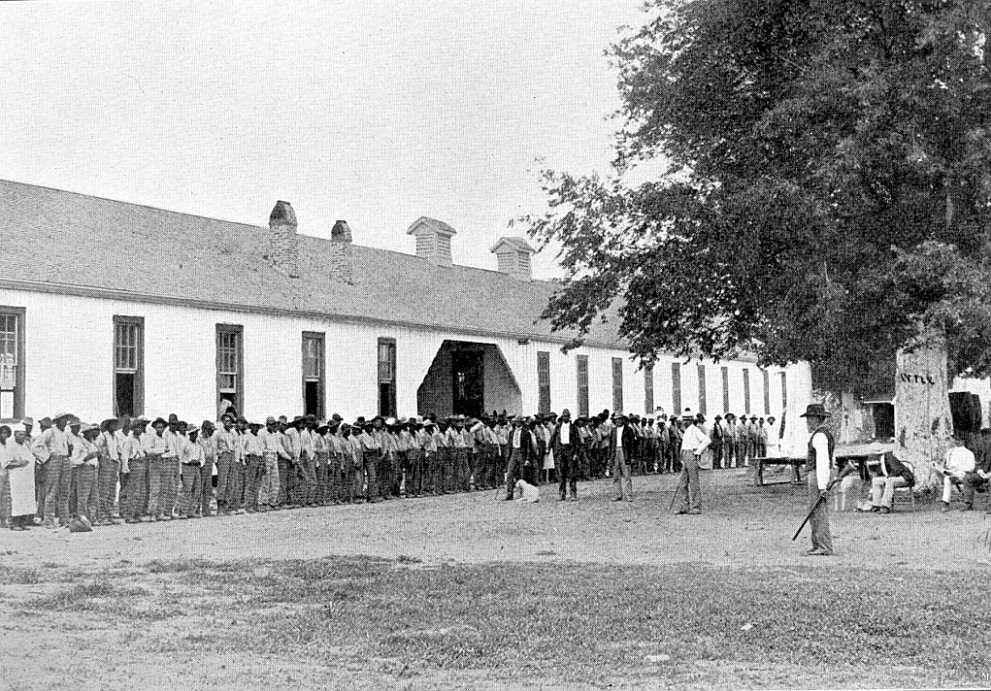

Following the Civil War, in 1880, the plantation was sold to Samuel Lawrence James, a former Confederate Army Major, who took advantage of the return of slavery-like conditions through the emergence of the convict leasing system. Through convict leasing, private corporations colluded with the criminal justice system to entrap, convict, and lease mostly Black people as incarcerated laborers. This practice became highly lucrative throughout the former slave states of the US South, with the state of Alabama generating 73% of its annual state revenue from convict leasing in 1898.

Conditions at the former plantation, now known as the James Prison Camp, became so harsh that they prompted the formation of the Prison Reform Association in New Orleans, which vehemently opposed the convict leasing system. The group’s advocacy alongside other prison reform groups eventually resulted in the banning of convict leasing in Louisiana in 1898.

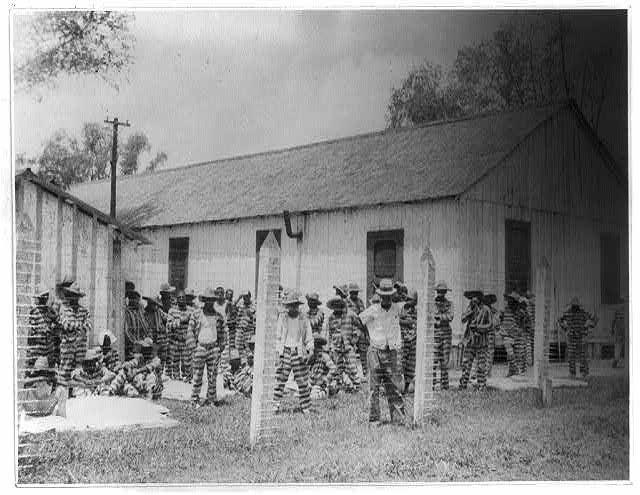

James died in 1894. In 1901, the state of Louisiana purchased the 8,000-acre plantation, establishing the Louisiana State Penitentiary on the grounds. And although Angola had gone from plantation, to convict-leasing camp, to prison, the basic conditions persisted throughout history—the brutal, forced labor of mostly Black people in the fields.

Authors Charles Wolfe and Kip Lornell would go on to label the “Angola” prison as “probably as close to slavery as any person could come in 1930.” Louisiana State Penitiary staff “ran the prison like it was a private fiefdom,” they wrote in the The Life and Legend of Leadbelly.

Prisoners struggle for better conditions

Prisoners, although effectively re-enslaved on the grounds of the Angola plantation, refused to remain slaves of their conditions. The history of Angola prison is as much a history of struggle of the most oppressed sectors of the working class as it is a history of brutality within the prison system.

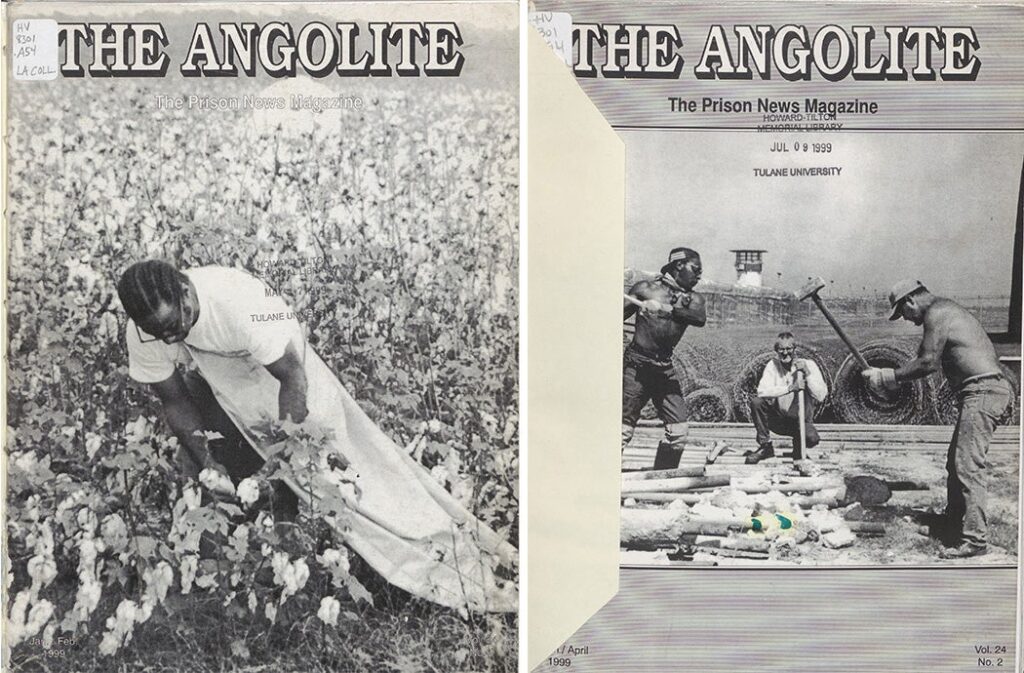

As conditions at the prison continued to deteriorate, especially following staff and budget cuts after the Great Depression, current and former prisoners put themselves at the forefront of the struggle for reform. In 1943, former Angola prisoner William Sadler published “Hell on Angola,” as a series of articles in The Angolite, Angola’s prisoner-operated publication. Sadler, who was nicknamed “Wooden Ear” due to injuries sustained in an attack by a prison guard, dedicated himself to reforming conditions within his former prison.

By 1951, prison conditions had deteriorated to such a level that 31 prisoners sliced their own Achilles tendons in protest and to avoid overwork in the fields—a somewhat common form of self-mutilation and protest by prisoners throughout the US to avoid overwork and torture by guards. By May of that year, what became known as the “Heel String Gang,” or inmates of Angola that had undergone this painful form of protest, had grown to 55. The protest, though violent, was ultimately successful, and corporal punishment was formally abolished at the prison.

Angola has incarcerated some notable fighters for Black liberation, including Ruchell Magee, who was subject to what some dub a “legal lynching,” being sentenced at age 16 for “aggravated attempted rape” for his relationship with a 23-year-old, married white woman. After finally leaving the fields of Angola at age 23, Magee would go on to be reincarcerated in Los Angeles and later participate in the Marin County Courthouse Rebellion, dubbed a “slave rebellion” by some in the Black liberation movement.

Some of the most high-profile incarcerated organizers and freedom fighters were known as the Angola 3—political prisoners Albert Woodfox, Herman Wallace, and Robert Hillary King. The Angola 3 were imprisoned at Angola from the 1970s to the early 2000s and 2010s. Woodfox and Wallace were placed in solitary confinement for over 40 years—the longest period of solitary confinement in US history.

Beyond being subject to the longest periods of solitary—international recognized as a form of torture—Woodfox, Wallace, and King formed what some label as the first official chapter of the Black Panther Party behind prison walls.

Prisoners keep up the fight today

In the past few years the struggles of Angola prisoners have revealed that conditions at the prison remain essentially as a modern day form of slavery.

In September of 2024, several prisoners filed a class-action lawsuit challenging the harsh conditions of forced farm labor at the prison. Angola’s mostly Black inmates are still forced to pick cotton in the same fields as they did before slavery was abolished, often in conditions of extreme heat.

“I saw guys collapse,” said Angola prisoner Lamont Gross of his time working Angola’s notorious “farm line”. “There were dudes that got heat stroke. There were dudes with underlying conditions, older or had some sort of disability, but they had to go out there, too.” Harkening to conditions of slavery, plaintiffs in the class action suit claimed that they fainted due to their working conditions and were punished for it.

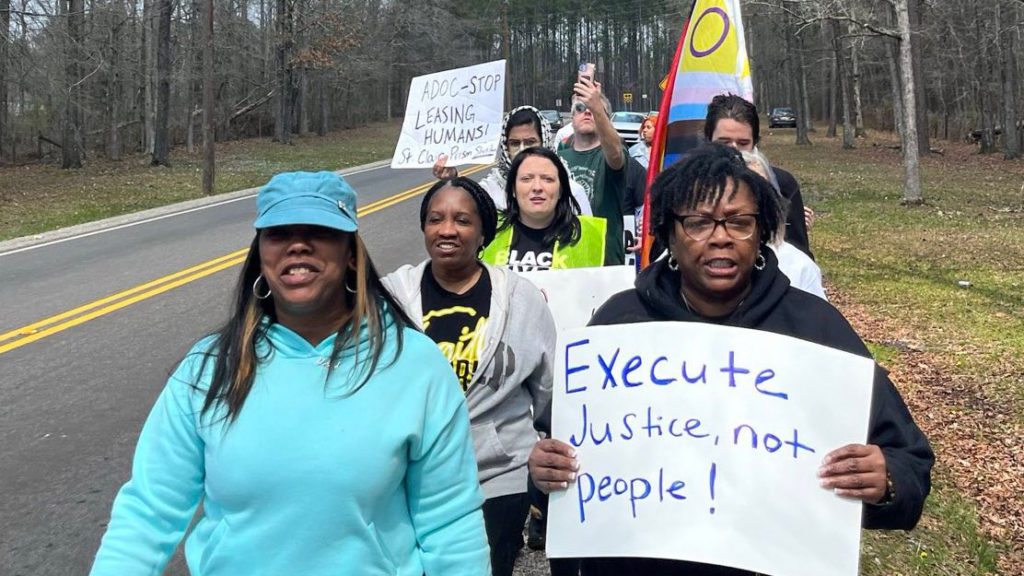

Across the US, prisoners are struggling against the behemoth of mass incarceration, much of which involved similar conditions of modern-day slavery. In Alabama, for example, prisoners have organized several rounds of state-wide shut downs of prison labor. These Alabama incarcerated organizers, led by a group called the Free Alabama Movement (FAM), want more than just better conditions—they have called for an end to prison slavery.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.