The sign on Eric Capenhurst Gentry’s office wall contains only three words. But they sum up how he changed his life.

“Education,” it says. “Not Incarceration.”

College advisor Eric Capenhurst Gentry, who experienced incarceration, poses for a graduation photo on campus at ASU, where he earned an online Master of Social Work in May. Photo courtesy Eric Capenhurst Gentry

Download Full Image

Gentry knows plenty about both. Having experienced incarceration ultimately strengthened and refined him, he said, although it wasn’t until the second of two prison terms when he resolved to change his ways. His onetime destructive path is today one of hope he shares with others.

Gentry, who earned an online Master of Social Work from Arizona State University, teaches and advises students at a community college in Hayward, California. The job also involves visiting correctional facilities to talk to people who have been through a similar journey.

Now Gentry is a world away from his teenage self.

At 18, Gentry, who grew up in Vallejo, California, was charged with first-degree murder, punishable by 25 years to life in prison. He was eventually convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to six years in a California maximum-security correctional facility.

He said he was offered no rehabilitation or skills to reenter society. Upon release, without a plan to do better, Gentry fell back on familiar behaviors.

“After only two months of freedom, I was arrested for two counts of assault with a deadly weapon stemming from driving under the influence,” he said.

Only in his 20s at the time, under California criminal law’s “three strikes” rule, Gentry would face a life sentence again if he was convicted of one more felony.

“I was facing more time in prison than I had been alive,” he said.

He was sentenced to two years. This time, though, he said he vowed to change his behavior once he got out.

“My then-girlfriend — now wife — began talking to me during my second prison term about college. After I got out of prison, I moved in with her and decided to try out Chabot College,” Gentry said. “This was spring semester 2012, and I have loved college ever since.”

Gentry earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology, summa cum laude, in 2017, then began providing outreach case management to those experiencing homelessness in Oakland, California. Two years later, he began an on-campus support group at Solano Community College, where he had attended, for formerly incarcerated students called SOAR (Students Overcoming Adversity and Recidivism).

From there, he began coordinating a program for former inmates called RISE (Restorative Integrated Self-Education) at Chabot College in Hayward.

In 2020 Gentry began ASU’s Master of Social Work program with the goals of becoming a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW) and teaching classes inside jails and prisons. He earned his master’s degree in May 2023.

“I now have a beautiful life. I have been married 11 years this July, own my own home, and have two beautiful baby girls (ages 1 and 3),” Gentry said. “I am fortunate to be free and do not take any moment for granted. I aim to give back and help many people overcome the adversities in their lives.”

Read on to learn more about Gentry and his ASU journey.

Editor’s note: Answers may have been edited for length and clarity.

Question: Tell us a little about your early years.

Answer: I was raised in Vallejo, California, in a blended family of seven children and two adults. I am of mixed race, Hispanic/Indigenous/white, and up until the age of 10 or 11 I was raised in a very poor neighborhood in a former drug house. My family was on public assistance and struggled to raise such a large family.

During most of my childhood my mother was addicted to drugs and alcohol and would disappear weeks at a time in her addiction. During this time, I began to gravitate toward older cousins who participated in gangs, as well as older siblings. My grades began to decline and soon I began to use substances. Eventually I dropped out of conventional high school and slowly spiraled into addiction and criminal behaviors.

Q: What led you to decide to pursue an MSW from ASU?

A: After spending so much time in recent years motivating and mentoring others from similar backgrounds as mine, convincing others of the life-altering opportunities that education provides, I began to take heed to my own message. I knew that there was another degree that would set my career apart and open even more opportunities to assist currently and formerly incarcerated students.

I am now the full-time RISE program manager at Chabot College, and I will hopefully be teaching in our Chabot classes inside of our county jail. I am also coordinating with another local college to teach inside of our county’s juvenile hall.

Q: What was your “aha” moment, when you realized you wanted to study the field you majored in?

A: I loved the study of psychology while in community college. … I loved studying politics and political science but was most fascinated by psychology. I had spent a lot of time in prison studying human behavior and wanted to learn more about the complexities of the mind.

However, I did not want to be boxed into private practice or limited in my career choices.

I … knew that social work offered a broader perspective and more career opportunities, including direct practice, policy advocacy, community organizing and program management. Additionally, social work uses a holistic approach to social intervention. We advocate for social justice while providing support to individuals and families.

Q: Why did you choose ASU?

A: I chose ASU because of the wide range of online programs it offered. … I knew that I could not do an in-person, full-time MSW program, and started to look for online and hybrid programs. My supervisor directed me to ASU after I looked at online or hybrid MSW programs offered by a few California State University campuses.

My supervisor sold me on ASU’s name recognition across the nation and its California-accredited MSW program. Once I connected with a transfer advisor, I was sold. I received so much support during my transfer and matriculation process. My success coach was a bonus as well.

Q: You expect to teach classes inside a county jail. What do you hope to share about yourself to your students that would be of most benefit to them?

A: Because of my bachelor’s degree in sociology and Master of Social Work degree, through the lens of sociology, I like to give hope to people who are incarcerated, many of whom say incorrectly that their lives are over. I love to go inside now and use my story to show people how higher education is the key to beating the system, to coming home successfully. You don’t have to get a master’s degree. But my focal point in my job and as a teacher is to share in spite of any felony convictions you have, you can still come home and be a therapist, be a business person. You can live those dreams, through higher education you can pursue those. …

I would say, “Your life is not over. Your life is not defined by this moment. You’re not a felon, you’re not an inmate, you’re a person.”

Q: What else do you hope to do with your degree?

A: I plan to remain the RISE program manager at Chabot, but I’m hoping to make a classification change to a counselor or coordinator position. This will increase the amount of counseling and therapeutic support I can give the students and allow me to teach on campus and in our jail program. I also plan to apply to other colleges that teach inside custody settings (juvenile hall, jails and prisons) to teach inside other facilities. I want to get licensed with the (California) Board of Behavioral (Sciences) as an LCSW and open a private practice providing therapy support to justice-involved individuals.

Q: What’s the No. 1 roadblock for people experiencing incarceration to change their lives so that they never are behind bars again? How can they best overcome it?

A: Reflecting back on my time, first, a lot of it is about instant gratification. You come home (from prison) and it’s hard to do something different. We spent years behaving a certain way, having criminal behaviors. Then you’re expected to switch that light bulb off, change overnight. It takes a long time to build up to that. Now I’m working on my health. I lost 70 pounds.

Second is financial instability. You come home and there are vast financial opportunities from selling drugs, versus applying for 100 jobs and getting 100 no’s, a paycheck for $800 versus making $800 in one drug transaction.

I help people think long term and have long-term goals. The longer you stay in that old life, the longer prison sentence you’re going to get. Is 25 years in prison worth that instant gratification?

In the world of art, Western European art historical canon and hierarchy often places “fine art” and “craft” at odds with one another.

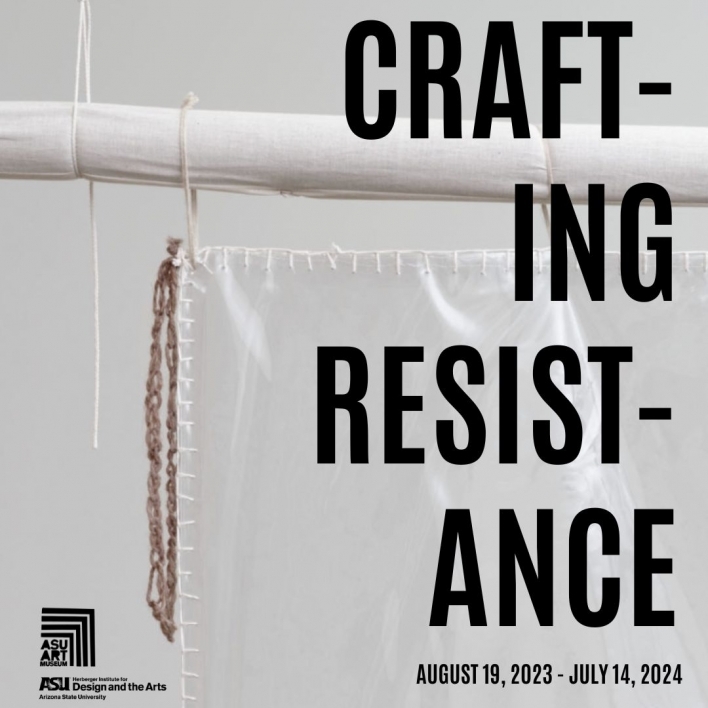

“Crafting Resistance,” an original exhibition of the ASU Art Museum on view from Aug. 19 through July 14, 2024, seeks to explore the ways in which we understand and view the term “craft” and its relationship to fine art.

Merryn Omotayo Alaka and Sam Frésquez, Bundles Past My Butt, 2021. Kanekalon hair and braid clamps, wire. Image courtesy Lisa Sette Gallery

Download Full Image

The exhibition showcases new and existing work by artists Merryn Omotayo Alaka and Sam Frésquez, both ASU School of Art alums, as well as Sama Alshaibi, Andrew Erdos, Maria Hupfield, Yasue Maetake, Jayson Musson, Eric-Paul Riege and Curtis Talwst Santiago. It is organized by independent curator Erin Joyce, with support from Abigail Sutton, ASU Art Museum Windgate Intern.

Joe Baker (Delaware), Bonn Baudelaire (Cocopah) and Sharah Nieto (Yucatec Maya) make up the exhibition’s advisory community of practice.

“Crafting Resistance” offers all visitors an opportunity to view and understand contemporary artworks and their relationship to fine art and craft. Performances and programming will also be part of the exhibition. Information on those events will be forthcoming.

Visit the ASU Art Museum for the opening reception on Saturday, Aug. 19, from 6 to 8 p.m. More details can be found on the museum website at asuartmuseum.org.

“Crafting Resistance” is supported by the Edward Jacobson Fund, Kevin and Alexis Cosca, Therese M. Shoumaker, and Christian and Allison Lester.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.