“The set-decoration and the art department worked miracles transforming the space.”

Photo: Shane Brown/FX

Okern, Oklahoma, is technically fictional. But thanks to the input of the series’ Native crew and the community members of its primary filming location, real-life Okmulgee, the Reservation Dogs hometown crackles with energy and life. It’s cliché to say a TV series setting is a character, but with its precise and unexpected details — as minute as the type of flowers used for a funeral service and as sobering as the reflection of moonlight on a dorm-room floor as two nuns drag a screaming child across it — Okern was. Every aspect of Reservation Dogs’ look was crafted with intention, and it showed onscreen.

“When we’re creating and decorating the sets, we’re thinking about the people who will be watching at home, sure. But we’re equally, if not more, thinking about the people who will be in the room when it actually happens,” says production designer Brandon Tonner-Connolly, who joined the series after its pilot and worked on all three seasons. “We’re thinking about the crew and cast who are from the community, and the people down the block who might stop by to watch filming. We want them to feel the spaces are right. It’s about that experience as much as the final product on film.”

Time and time again, the series asked its art team — led in season three by Tonner-Connolly and set decorator Tafv Sampson — to invite viewers into the rooms where Okern’s residents spend their time. Those locations roughly divide into two categories: The reservation’s homes and communal spaces are “washed with warmth and comfort and cozy,” reflecting the Native aesthetic Sampson grew up with in Okmulgee (her father is the late actor Tim Sampson). “There’s never any coldness or harsh lines; everything’s warm wood and soft goods and little lighting and handwritten notes and junk mail,” she explains. “Little things everywhere, that’s how my dad was.” Then, as the series progressed, it went darker, spending significant time illuminating the space that tried to stamp out and exploit Native identity: the Indian boarding school.

Depicting the range of Native experience was essential to Reservation Dogs co-creator, director, and writer Sterlin Harjo, as was filming nearly every scene on location in Oklahoma. Tonner-Connolly and Sampson spoke to Vulture about collaborating on the show’s definitive and most involved sets and how their teams worked to align these spaces with “the universe of Reservation Dogs,” as Tonner-Connolly puts it. “You’re giving people the opportunity to experience life in a different place,” he explains. “The character details we put into a set create intimacy, and intimacy builds empathy, and conveying that experience helps someone understand and feel another kind of person’s world.”

Introduced in the series’ second episode, “NDN Clinic,” the medical center that employs and treats many of the Rez Dogs’ relatives and mentors became a recurring location as well as the starting point for the formation of many unlikely bonds. It’s where Willie Jack decides to learn medicine from Fixico, Cheese is taken under the wing of his future adoptive grandmother, Irene, Bear and Jackie deepen their friendship (and possible romance), and Big and Bev start snagging. The space is decorated with an array of pieces from Native artists, including Sampson’s grandfather, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest actor and Native icon Will Sampson.

Brandon Tonner-Connolly: Each of the writers had a different story about spending a day endlessly waiting at the IHS. We wanted the viewer to feel lost, tired, and kind of bored when they step inside; people were telling me that was their state of mind when they’ve been in there.

Tafv Sampson: Everyone in the script is always like, “Oh my God, I hate this place. You’re just sitting forever and people are rude.” But there’s a really deep sense of community and sweetness to this set that’s very Native specific. Even my own dad and older people I know would go to IHS to hang out because there’s free coffee.

B T-C: We looked at actual clinics toward Okmulgee and outside of Tulsa, and it was going to be hard to not disrupt their operations. Our location manager, Chris Kucharski, was able to find this space — it’s a clinic in a strip mall on the outskirts of Tulsa open two days a week. We’re able to pay them a location fee and compensate them for our use.

TS: The exterior mural is by Yatika Starr Fields. He’s been in the community a long time, has known Sterlin a long time. Everyone knows Yatika. The building loves the mural, and they’re gonna keep it forever.

B T-C: He created a mural satirizing the idea of Western medicine being gifted to Indigenous people. The perspective is kind of off; there’s an eagle and it looks like it has only one eye.

TS: The artwork around the whole building, those are my grandpa Will Sampson’s paintings. He was known for being an actor, but he was also a painter and a rodeo star. It was season one and we were being real scrappy about everything. I had the contact sheet that a relative had taken of all of his paintings, and I handed them to Brandon, like, “Do you think this can translate these to the prints that we need?” And he was like, “Absolutely.”

When Fixico is in the hospital and the camera is panning by everyone in the hallway, those paintings are all my grandpa’s. I put my dad’s blanket on Fixico’s lap while he’s in his hospital bed. I was like, This is jam-packed with love here.

B T-C: We started with the color palette, and then these cheerful PSA graphics, which — as Sterlin described — are “uselessly optimistic,” especially the anti-diabetes posters. We looked at all the real-life examples and made them a hair less subtle. It was perfect and hilarious and kind of sad. We also collaborated with Ben Brown, who’s another local artist, to create this Spirit Anatomy poster. Rather than a regular anatomy poster, it reveals the culturally significant objects that make up Spirit’s life force.

This season, I pitched what I thought was an absurdly unsubtle idea of adding a buffalo mural to the break room. We were honored to have Johnnie Diacon come in and create this astonishingly beautiful, subtle piece of original art. He painted it on a Saturday. Nobody else was there, it was deserted and quiet. I came in just to hang out with him.

TS: He’s like the BFG: this big, sweet, comfortable Native man. He has such a sweet, soft voice and his stories are so hard, like a lot of Native people. They’ve had to endure a lot of hard things their whole life, but there’s such a groundedness and a calmness to him about the things that happened in his life and how he carries them.

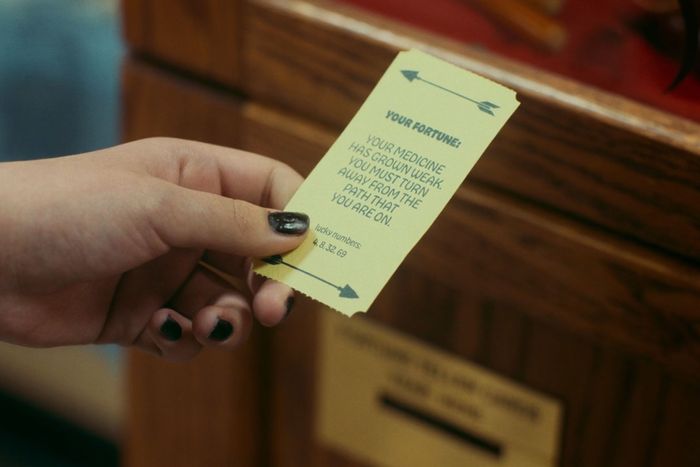

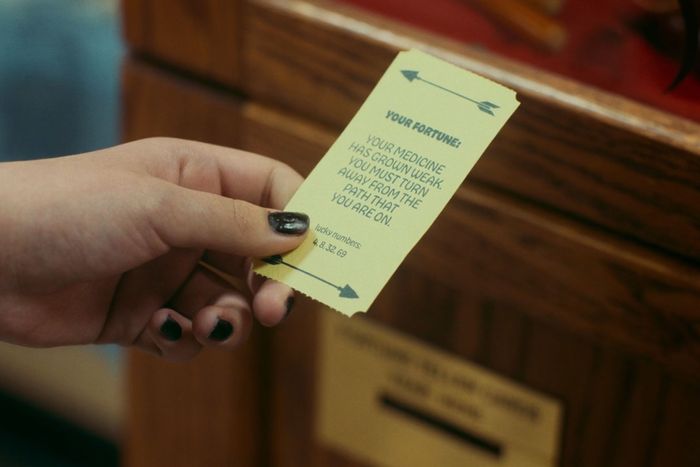

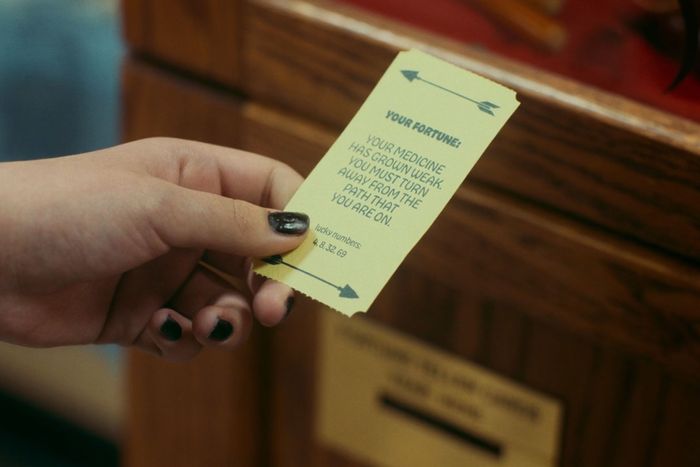

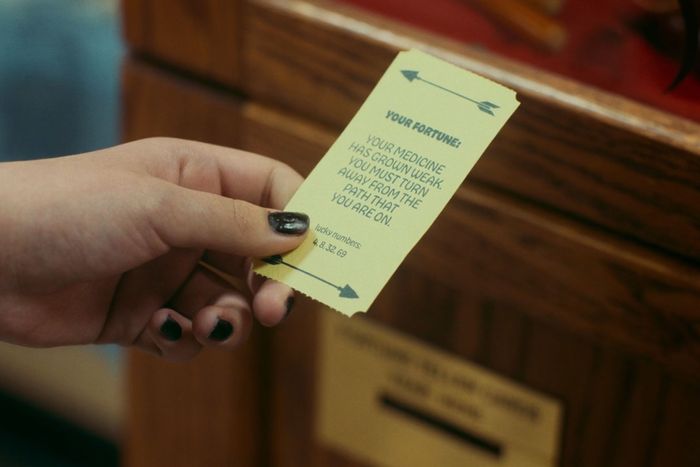

On the road out of Okern, this kitschy tourist spot holds a cacophony of somewhat offensive and clichéd Native-themed items that the production and set-decoration teams were given the freedom to dream up. The one scripted item: a Medicine Man machine, voiced by Dallas Goldtooth, whose fortunes are about as opaque as the advice Goldtooth’s spirit William Knifeman gives to Bear.

B T-C: We wondered, can we shoot in a real trading post? The closest one was about two hours away, and that’s too far. We found a great location closer to Okmulgee. It was a gas station on one side and a diner on the other. Tafv and the set decorator for season one, Javed Noorullah, did an amazing job of working with local vendors to rent all these materials. We had a lot of freedom to find the objects we thought were appropriate for that kind of a store. I do remember a conversation between myself and Sterlin: “How offensive should this be? Is there a limit?”

TS: What are you going to find in the Toontown version of Native American stuff? The things Native people pick up and say, “Are you kidding me?” We had Jinx spray: “Lift the hex with this aerosol spray!” It was actually weirdly hard to find some of the stuff in our heads, like teddy bears with headdresses. We’re like, Maybe people are a little more aware now than they were before. We wanted to have a Native American statue in the front, but it couldn’t be a good one. It had to be one that has, like, a crooked eye.

B T-C: Yatika again came in and painted this giant teepee structure and a Native American statue that we put outside, following the mandate that this should be a more unsubtle and borderline offensive space. In the convenience store section, we put graphics up on the wall that I had seen in a reference photo: a spear and a feather.

The Medicine Man was a question of, how much are we going to make it look like William Knifeman? Is it going to be too strange if it’s an exact replica of his face? Will that detract from the joke? We sourced a machine that was several states away. We put a wig on it and put the clothing on it, and we created the little cards that come out.

TS: It kept talking when it was not supposed to. [Laughs.] We had it in the office and we’re like, “This thing is unplugged, but it’s spitting out one last word. This thing is cursed! Don’t look it in the eyes!”

In season one, Elora Danan’s grandmother Mabel is physically around but emotionally absent — not nearly as close with Elora as Bear is with his mother, Rita, or Willie Jack with her father, Leon. The two don’t seriously discuss Elora’s present or future, and it’s revealed as the series progresses that Mabel withdrew after the death of Cookie, her daughter and Elora’s mother, when Elora was 3. In season two, Elora returns to Okern when she learns that Mabel is dying, an event that unites generations of the community. In the bottle episode that takes place entirely inside Mabel and Elora’s home, and particularly in Mabel’s bedroom, Okern’s elders and aunties honor her life and guide her passing.

TS: When someone is passing away on TV, it’s always a very solemn scene, and there’s tension and quiet. We didn’t want that for Mabel. We wanted the house to feel alive. That’s how it is: The community comes together and there are kids running around and auntie drama happening in the backyard. We wanted her room, her space, and that house to feel jam-packed full of that community, even if it’s just her and Elora sitting there. My dad had passed the exact same way; he was in hospice, and as it was coming toward the end, he wanted to be at home. I had a real emotional time making this set: What would I have wanted, had I had the time and mental wherewithal to actually plan a space like that?

B T-C: Anybody who’s been in this sort of tribal housing is going to recognize this layout and will feel a sense of familiarity and authenticity. Everything going into Mabel’s room had to be special and evoke the proper emotion.

TS: I wanted it to be filled with everything that meant something to somebody on this show who had lost a loved one or a family member. We went around to the crew and asked, “Do you have anything you would like to be in this room with her?” Neosha Pendergraft’s mom, Shan Goshorn, was an amazing painter, so we got her paintings. TJ Redcorn was our PA and we have an original painting by his family member. We have my auntie’s “Hunk Wall” — she was obsessed with Bon Jovi and Marlon Brando, and had taped magazine cutouts of her hunks on this board. I put my dad’s second-grade picture in the lampshade, so you can see it when Fixico’s singing and lighting sage. We had some necklaces, we had some actual clothing; there’s a jacket hanging on the wall that belonged to a crew member’s relative who had passed away. We had a traditional Creek love doll from a crew member hanging next to Mabel’s bed. They’re very sweet and beaded and felted, and we put it right next to her headboard so it was almost watching over her. Some things were really sacred objects and some were just silly, but they carried a lot of weight. About ten to 15 people gave us things — the number of things in the room was in the 40s.

We all took turns coming into that room and crying. I sat and let myself feel everything of all the people that were in this room — their things that they left behind that their loved ones hold dear. It was such a strong room energetically.

B T-C: When I’m out scouting homes, I always respectfully ask if I can take pictures of the photos on the wall or the Bible quotes on the fridge or the cereal on top of the fridge. Those are the tiny details that create the world. For Mabel’s house, I drove the graphic designer crazy thinking about what to create for the fridge. I wanted this bingo card promotion from the Okern Times, and then Rob-n-Cleo’s and other local businesses’ advertisements next to this bingo card.

A major resource was the family photos of people from the community who are in the art department. For Mabel’s, we had so many great photos from Sierra Revis, an assistant art director who showed us her aunt’s house in Oklahoma. One photo had a burn mark from an iron on a rug and I was like, This is what we need to tell this story. I had something like that in my house growing up. We did bring in an iron, heat it up, and actually burn the carpet to tell the story of, maybe Mabel was ironing and a tiny Elora Danan knocked the iron over. We also did a collage for Elora Danan’s bedroom wall. Actress Geraldine Keams gave us an amazing photo of her from 30 years ago, holding a Budweiser on a couch.

Photo: Shane Brown/FX

Photo: Shane Brown/FX

In season-two episode “Offerings,” Willie Jack goes to prison to visit Hokti, her aunt and Daniel’s mother. Played by Lily Gladstone, Hokti turned away from her family after her son’s suicide; the only thing hanging in her cell is an old photograph of Daniel. But after snacking on Flaming Flamers and cracking open cans of Skux — all overseen by a spirit mentor played by Sampson herself — Hokti guides Willie Jack to an understanding of her place within generations of Native people persevering, coming together, and watching over each other.

B T-C: The locations department immediately said, “We have to be in Tulsa to make this work logistically,” and there was only one possible location, the Adult Detention Center on Charles Paige Boulevard. It was an abandoned, dilapidated prison the county was using for storage. Every square inch was jammed with massive office equipment and other detritus, and there was no water, no power, no lights, nothing. It had been completely shut down. We had this insane cleanup effort spearheaded by the locations department, and then we built different walls to have the layout we wanted. We ended up painting and we brought in all our own signage, our own vending machines.

We needed prison tables, and we didn’t have the time to ship them in from a prop house — there are no prop houses in Oklahoma, which is part of the glory of the show; everything feels so original and so real because it is original and real. Prison tables are not something you can fake by going to Bed Bath & Beyond. We needed to steal them from another part of the jail. Our set-decoration team spent days grinding out these prison tables that were bolted into cement, then hauling them over to our actual set and securing them there. It was hilarious because you’d be scavenging for something you wanted, you’d see it in another room and try to get in, then realize it was securely locked because it’s a prison. And nobody had the key. [Laughs.] The set-decoration and the art department worked miracles transforming the space. It was totally worth it for the amazing scenes with Lily and Paulina and Tafv in there. The photo of Daniel was provided by actor Dalton Cramer. We had a lot of great family photos from him, and Sterlin chose the one in that episode.

Shane Brown/FX

Shane Brown/FX

In the third season, Bear gets separated from the Rez Dogs on the way home from California and is abducted by an older man who talks about preparing for the arrival of alien “star people,” tends to a greenhouse full of eggplants, and has a connection to Okern that Bear doesn’t immediately pick up on. Played by Native icon Graham Greene, Maximus has a central role in the series’ final episodes, and his compound had to reflect an initial ominousness that gives way to his later reveal as a Native elder in need of friendship.

B T-C: We really had to scale up to build the world of Maximus. This was an opportunity to show a vision that was cinematic and a little grander than what we’ve seen in Okern previously.

I scouted different properties until I saw this decrepit, about-to-fall-over house, and I liked that it could tell a story: He grew up in the house and when his parents passed, it got too deteriorated to live in, so he brought in a trailer and moved next door. The other thing I loved was this old gnarled tree with branches that twisted out in every direction in the back. The branches touch the ground in front and part slightly to form a natural doorway. It had this fantastic mythical look to it.

TS: It was a really interesting set to make, because when Bear wakes up, it’s supposed to be the dark, scary, typical conspiracy-theorist home we know very well onscreen. But later in the episode, it had to become a Native home that we recognize as part of this show, that has the warmth and the details. How do we make this place seem kind of terrifying, but there’s tenderness surrounding it and you don’t want to leave? The pillowcase Bear is sleeping on was my great-grandma’s pillowcase. On Maximus’s counter, we have boxes of Little Debbie Star Crunch cookies. We ended up consulting with amazing people like Harvey Pratt, who is a Native forensic artist. He gave us his prints.

B T-C: We had to transform the derelict trailer interior, build the greenhouse with rows of eggplants, build the stone-wall tin-roof shed to hold Maximus’s treasured objects, and figure out how to create the escape tunnel. We researched what the “star people” concept meant in Indigenous culture, we spoke to elders and other people in the community about their experiences, then we wove all of that into the sets. We had a swirling star chart painted on the wall next to where Bear would wake up. I don’t think you saw it in the episode, but we had the night sky painted on the ceiling of the trailer so Maximus could sit on his couch and look up and see his idea of the stars above him. In the greenhouse, we have a medicine-wheel-like symbol with a star chart painted on the wall. The tunnel has similar symbols in it for Bear to find glimpses of. We brought in vintage wallpaper and wood paneling to create some visual chaos with all the different newspaper textures inside the trailer. We had to source 100 eggplants out of season from an Osage greenhouse.

TS: We wanted to nod to the 1970s episode as much as we could, and the kids’ involvement with the American Indian Movement. You’ll see a newspaper clipping behind Bear’s head when he wakes up and an upside-down American flag on the fridge.

B T-C: There’s an American Indian Movement protest poster in the shed behind him and Bear when they’re watching the footage of his friends in the ’70s. That same poster is in Maximus’s dorm room looking new.

“Deer Lady” is the most drastic departure from Reservation Dogs’ established style. Peppered with flashbacks to one of the notorious boarding schools that abducted Native children from their families and violently forced assimilation upon them, the season-three episode is both a horror movie and an origin story for Okern’s mythical vigilante. Its period-piece accuracy was accomplished through what Tonner-Connolly describes as “copious, copious” research into the destructive impact of boarding schools. What no one could prepare for, though, was the electrical fire that burned down the warehouse holding production’s materials for the episode.

B T-C: Before we started the season officially, we were trying to find any photo of a boarding school from the late 19th century to the mid 20th century, especially on the Plains. Tafv went to Anadarko, Oklahoma, to meet with people at the historical archives and gather images, and we had a consultant come onboard, Denise K. Lajimodiere, who is the author of Stringing Rosaries: The History, the Unforgivable, and the Healing of Northern Plains American Indian Boarding School Survivors. She answered our many questions about plates, spoons, bedding, desks, everything.

Once we had all the research, we found Bacone College. It allowed us to shoot almost everything from that episode on this one campus. Danis Goulet, the director, came in with amazing visual ideas, including giving the episode a very ’70s-horror aesthetic with long lenses and this palpable sense of dread. We talked about Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria and a few other films as color-palette references. The genre aesthetic was a nice way of making the incredibly weighty subject matter a little more digestible, so it felt fantastical or like a dream rather than a gritty doc. It also set this particular episode aside in its own very separate universe.

We started in this giant hall that was being used as a storage room. It had mounted flatscreen TVs, low-pile carpet, reminders that we were in the year 2023. I looked at the references and picked out some period elements that were important, like a hardwood floor with very high gloss so it kicked back moonlight during the night scenes and added this mythical feeling. We incorporated small decorative crosses on the wood paneling so you always feel hemmed in by the religious element of the surroundings. Our art director, Matt Hyland, and our construction coordinator, Aaron Maier, were able to build and install this flooring, this paneling, and a million other details in this very large space. The whole thing has a really heavy, emotional weight of this terrible history. We had to be really mindful of the toll it may take on people in the art department and everybody else.

TS: We had a lot of crew members who had relatives at boarding school at that time. There was a lot of crying. That episode was not only emotionally tough, but our warehouse burned down the week before with everything in it. They ruled it to be an electrical fire. Because of time and money, we had to keep going. There was no way we could stop filming. I was like, Am I going about this with the respect that it needs? I didn’t smudge the beds when they came into the warehouse. I was going a mile a minute. I was like, We all need to take a moment and remember what we’re doing here.

B T-C: I was there the night of the fire with Tafv. We saw the construction coordinator’s tools, the scenic department’s paints, the set-decoration department’s stuff. There were some elements that were priceless. We had rented period desks from a museum. All of it was destroyed.

We had a big team meeting the next morning and listened to how everyone was feeling, then decided to go forward and do our best work without looking back. That warehouse was our base of logistics — where all the construction stuff was, where we cut all the wood, where we paint. The construction department set up a satellite shop at Bacone College and were living out the back of a trailer. It was like, yes, this is terrible; yes, we’re all logistically and emotionally affected by this. But at the same time, we’ve got to do this thing. If we don’t do it, nobody’s gonna do it. And it’s got to get done, because this is an important TV show and an important episode.

TS: We all had our smudge kits and we’re like, “Get in line, everyone!” I made sure to smudge all the beds and all the desks afterward because objects carry energy. Even if these aren’t things from the actual time, it’s what we’re representing, and it’s powerful stuff. There was a lot of hurt being brought when we were making this. We’ve got to protect each other.

Two episodes after “Deer Lady” comes another period piece: the 1970s-set “House Made of Bongs,” which takes place at the same school (now with “Indian” removed from the school sign) and introduces us to the Okern elders’ younger selves. Maximus, Bucky, Brownie, Irene, Mabel, and Fixico all appear as teenagers; so too do a variety of Easter eggs for the series, including nods to family members of the series’ crew.

B T-C: The 1970s episode feels a little lighter, a little more familiar, a little bit to digest, both because tonally the script is more like Dazed and Confused and because these spaces in the 1960s and 1970s look like a familiar idea of high school for most people. We used Rogers State University for the classroom, hallway, school exteriors, and dorm rooms. It also gave us a big parking-lot scene. We dressed another part of campus for the Cheese post-apocalyptic video-game intro in the fishing episode.

TS: Sterlin’s mom and my dad were homecoming king and queen together at Oklahoma’s Sequoyah Indian Boarding School in the ’70s, which we did not know. They were high-school sweethearts; my dad was a basketball star and Nan, Sterlin’s mom, was this beautiful, smart, creative girl. When we were putting together this episode, we needed bunk beds; I was like, “I’m gonna contact Sequoyah and ask, ‘Do you guys have pictures of these so we could start to source?’” And the woman I work with was like, “Not only do I have pictures, we have a whole basement full of the beds from the ’70s that we never got rid of.” So we got the actual bunk beds our parents slept in and tagged them “Tim ❤️ Nan.” The coincidences that happened, the things that fell into our laps — I couldn’t have dreamt this. It’s all meant to be.

B T-C: The most fun for me was adding all the different details to the ’70s dorm room: Here’s the movie poster where we’re going to establish that Maximus is very into film. We really wanted a Two-Lane Blacktop poster, but we couldn’t get it at the last minute. Someone in the set-decoration department put in a little matchbox car of the GTO from that movie on top of the film canister on Maximus’s desk.

TS: The book Bucky gives Maximus, Mirrors Made of Millennia — we had a different book, House Made of Dawn, that he was supposed to be carrying, but the rights didn’t clear. We were like, Let’s just make up a book. Tazbah Chavez, one of our writer-directors and producers, is an amazing poet. She had written a poem called “Mirrors of Millennia,” which is a beautiful title, so we got our graphic team to mock up some artwork and they threw my name on it as the author.

B T-C: Sonic being an Oklahoma thing, it was a collaboration between production and our locations department talking to them, and they said yes to using their name. I was searching for a location we could paint and make our own signage for, and we’re lucky we found a fast-food restaurant ten minutes away. We created our own sign, painted it red and white, added the period Sonic menus — they gave us permission so we could do that.

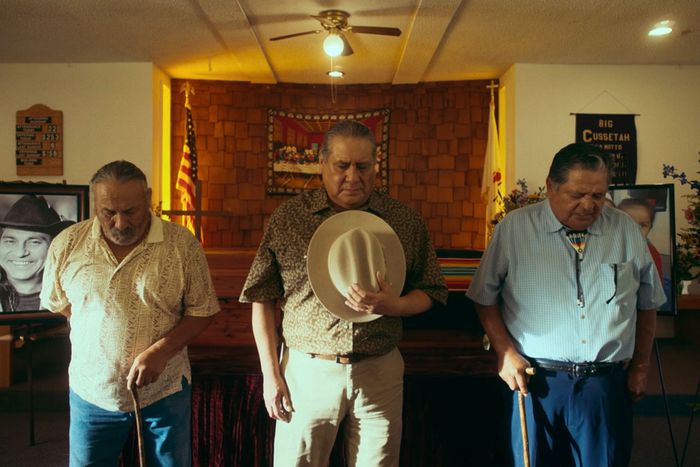

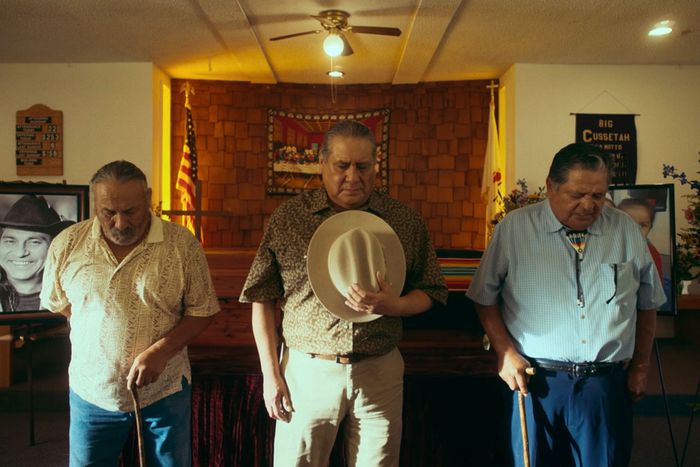

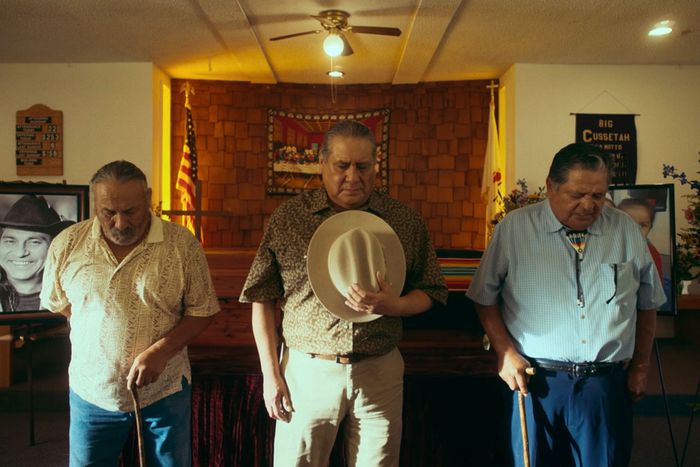

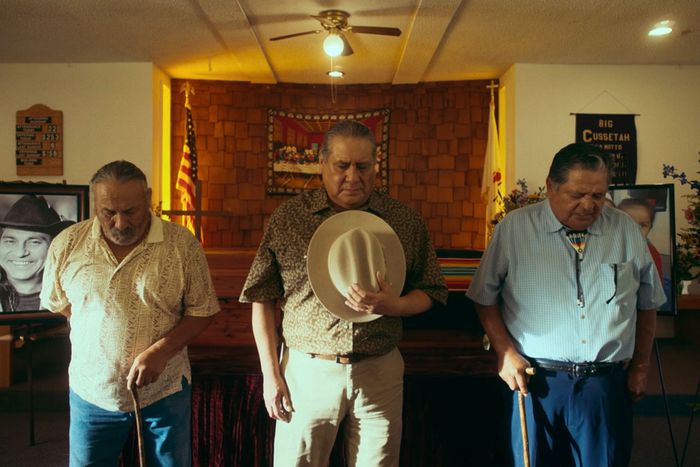

In series finale “Dig,” the entire Okern community gathers — as they did in “Mabel” — to say good-bye to medicine man Fixico at a church and cemetery that haven’t appeared in the series before. Nearly every Native character previously seen on the show pops up in the episode, either hanging out outside with the elders, cooking in the kitchen with the aunties, or digging the grave with the uncles overnight. As one of the last scenes filmed for the series, the ceremony was a meaningful end for the crew’s years of work.

TS: That’s a real Native church an hour from Tulsa. Wotko Long is everywhere in this show — he’s playing the security guard, he’s singing next to Mabel. When we went to scout the cemetery, there’s a guy on a lawnmower mowing between the graves. I was like, “Is that Wotko?” It was! He tends to the grounds of that church. In real life, he’s so part of the community. And we’re all going around looking at the names and saying, “I think we might be related to that person.”

B T-C: We wanted to be respectful of everything and everyone here. We ended up getting a space approved by the cemetery for digging the grave and we came up with a chart of how it would look for each scene. We dug a full grave in one spot and then a couple feet away dug half a grave, and then we were able to shoot back-and-forth according to what the scene indicated.

When we were digging the actual grave, the backhoe wasn’t totally cutting it. We had our people actually digging a grave by hand. They got down to four feet and they were like, “It’s bedrock after this, is this good enough?” I was like “No, it’s not, unfortunately.” [Laughs.] It’s got to be as deep as the actual grave would be. This is such an emotional moment. We’re going to have people standing in the grave. We don’t want 100 people out here filming this scene and then somebody’s like, “Well, it might be a little shallow.” We ended up having to jackhammer through bedrock to get it down to six feet.

TS: We added some curtains to the interior of the church. Fixico is such a vibrant part of this show, and we really wanted his arrangements and feeling of his casket to be as abundant and as warm as the summer they’re in. We decided on wildflowers, because that’s what he is. Richard Ray Whitman gave us his own blanket, which is really special.

B T-C: We built all 30 benches for that outdoor space. We left them with the church so they could use them after that. It was a really special experience being in that space at night, shooting the last couple scenes of the entire show and having everybody together. After we wrapped, we all went over to a space next to the church outside of the cemetery and Sterlin got up and gave a speech about the show and his feelings and thanking everybody. Everybody hugged and had a nice sort of reminiscence over the past couple of years. There was not a dry eye.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.