Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly stated that Bryonn Bain is the director of the Prison Education Program. In fact, he is a founder of the program, but no longer serves as director. In addition, the original version of this article incorrectly stated that Bain is an associate professor of African American studies and world arts and cultures/dance. In fact, he is a professor of African American studies, world arts and cultures, and law.

This post was updated March 17 at 1:34 p.m.

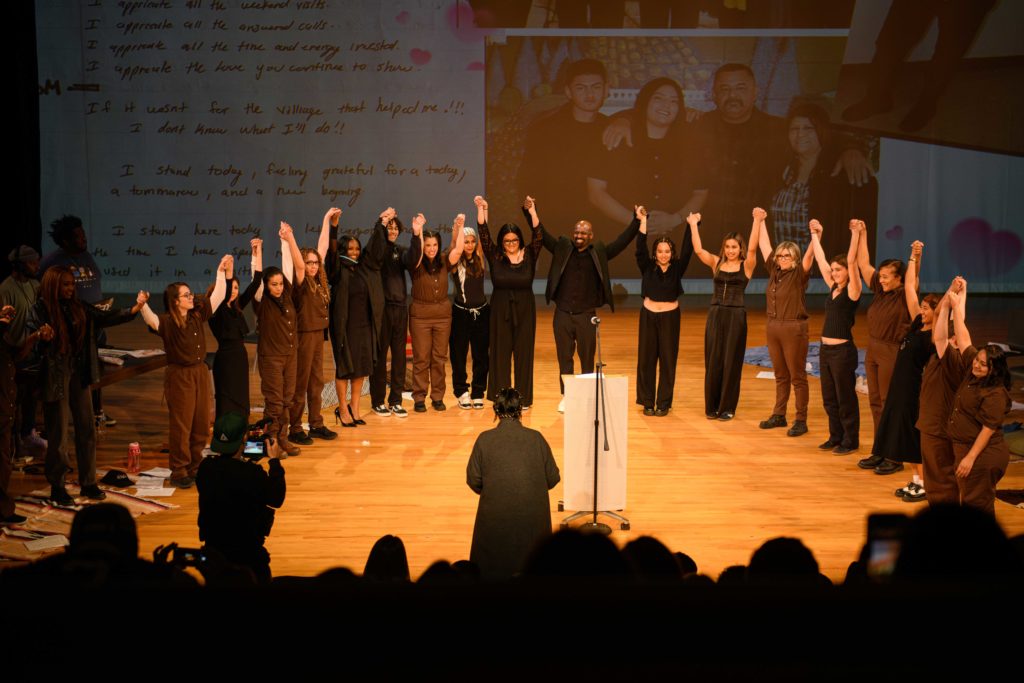

The Prison Education Program at UCLA hosted a spoken poetry recital in Kaufman Hall on Friday.

The performance served as the final project for African American Studies/World Arts and Cultures, taken by 12 UCLA students and 12 women from the Victorville Federal Correctional Institution. Bryonn Bain, the founder of the Prison Education Program, taught the class.

In the performance, students sang, danced and read spoken word poetry about motherhood, femininity, incarceration and facing racism. Some students also discussed geopolitical topics in their pieces, with mentions of recent abortion bans and the ongoing Israel-Hamas war.

Bain, a professor of African American studies, world arts and cultures, and law, said the class marked the second time he taught spoken word poetry to a group of UCLA students and incarcerated scholars at Victorville. In order for the final to be taken, the warden of the institution, among others, granted special permission for incarcerated scholars in the class to visit campus for the performance, Bain said.

Poetry is important for humanizing people in correctional institutions because the prison system takes away so many opportunities for expression from the people within it, he added.

“Art is transformative. I think art changes lives,” Bain said. “Art is about and poetry (is) about reclaiming our humanity and particularly for folks who have historically or systematically been dehumanized – from communities that have been dehumanized. Whether it’s women, people of color, working and poor folks, we know that poetry and art reminds us of our shared humanity.”

The Prison Education Program started in 2015 after 139 incarcerated individuals from the California Institution for Women, a state prison, wrote to UCLA requesting a bachelor’s degree program, Bain said. He added that the program is important because most other programs offered in prison are led by community colleges and only offer associate’s degrees.

Bain said during a typical week of the class, UCLA students leave campus at around 7:30 to 7:45 a.m. to travel to the prison, adding that the class runs from 10 a.m. until 1 p.m. before they drive back to campus. Keila Windom, a fourth-year world arts and cultures student, said the class did result in a significant commitment, especially for commuter students like her.

Although Windom said she did not know the class was part of the Prison Education Program when she first enrolled in it, she appreciated it because her father was incarcerated. She said she found the class healing, allowing her to write a poem about her dad and explore feelings that she had previously repressed.

The class focused on poetry that was intertwined with 20th- and 21st-century social and political movements, including from the beat poets, the hip-hop generation and the Harlem Renaissance, Bain said. Spoken word poetry is an accessible form of self-expression because it does not require extra resources such as clay or a musical instrument, he added.

“Spoken word is so important in every spiritual tradition known to humankind. … The power of the word is emphasized,” Bain said. “If you have access to language, if you can write, you can use words in ways that can be magical, that can be transformative, that can be liberating.”

Sofía Salas, a third-year gender studies student in the class, said the curriculum taught her the power poetry can hold as part of social justice movements, allowing for more empathetic understandings than just statistics.

Because of the rules that apply to visitors of the institution, the class had a no digital devices policy. Bain said the policy allowed UCLA students to be more present than they would be in ordinary classes.

Windom said she learned from the incarcerated students in the class, adding that she hopes they got as much out of the class as she did.

“I hope that they will leave this experience feeling heard and cared for and nurtured and loved and held,” she said.

Individuals from the Victorville Federal Correctional Institution were not able to be interviewed for this piece.

Bain also said when the class was taught last, it even led to one participant’s early release into home confinement after a warden watched her performance for the class.

“She saw her as a person, as an artist,” Bain said. “She ended up signing her paperwork for her to be released four-and-a-half years early.”

In the future, Bain said additional resources and political will are needed to ensure that the program can continue to serve historically disenfranchised people. He added that he hopes deans, departmental chairs and other faculty will increase their desire to expand access to a UCLA education after seeing the work his class has accomplished.

“We cannot do this work unless we continue to grow the support – the moral support, the financial support, the institutional support – and so we need that for every angle, every dimension of the campus and from those outside for whom this matters,” he said. “We believe this is the civil rights and human rights issue of our time.”

Lochlain Steere, a second-year English student in the class, said he hopes the performance will motivate students to take classes with the Prison Education Program and combat the negative stigma that has historically been associated with incarcerated scholars.

Salas added that she has already recommended taking classes in the program to her friends.

Bain said he hopes people watching the performance will take away the importance of his program’s vision and the opportunities to get involved with facilitating it. He added that overall, the class and performance emphasized the importance of common connections.

“Poetry reminds us that we all have these connections beneath the skin that we’re bound by, that we’re connected by, and it gives us a vision of what’s possible by demanding that we allow our imagination to go places that it hasn’t gone before,” he said.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.