APPLETON – Twenty years ago, Appleton became the first police department in Wisconsin to implement a new approach to policing incidents involving mental illness.

It was 2003. John Wallschlaeger, then a newly sworn-in Appleton Police Department officer, had read about a new model of policing called Crisis Intervention Teams that was finding success in other parts of the country. He brought it up to the police chief, who gave him the green light to attend a training in Ohio along with members of the Fox Valley branch of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

By the following year, Appleton started the state’s first Crisis Intervention Team, or CIT, program.

Officers who receive CIT training learn how to address people in the community facing mental health crises in a way that prioritizes de-escalation and diversion from the legal system.

“Under the state law, law enforcement has the authority to detain someone, and hospitalize them, and take away their civil rights so that they can receive mental health assistance. But if you have that huge responsibility, where’s the training?” Wallschlaeger said. “CIT was the answer to that.”

Two decades since its start in Wisconsin, CIT has been a key part of improving police responses to mental health crises. Law enforcement and mental health professionals say that the program can continue to grow and help more people through further education, destigmatizing mental illness and building upon existing resources for people in crisis

RELATED STORY:Wisconsin’s treatment courts prioritize rehabilitative needs and reduce recidivism

Fatal shooting prompted creation of CIT

Also known as the “Memphis Model,” CIT was created in 1988 in Memphis, Tennessee, after police killed Joseph Robinson, a 27-year-old man armed with a knife. Police responded to the scene after Robinson’s mother called police, fearful that her son would kill himself. Instead, two officers shot and killed Robinson. The incident prompted calls from community members to find ways to better address mental illness and policing.

It’s a series of events that has been seen across the United States and the world. According to a 2015 study by the Treatment Advocacy Center, at least 25% of all fatal police encounters result in the death of someone with a severe mental illness. That percentage is a conservative estimate, because most police departments, including Appleton, don’t track the role of mental illness in police encounters. Research from places with official government data — including Las Vegas, Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom — shows the percentage might be closer to 50%, the study said.

Other factors, like race, also complicate this data, as national studies and surveys show people of color are more likely to not receive treatment for mental illness and experience police misconduct.

Because CIT is a relatively new program in much of the country and there are not widespread data collections, studies have not been able to measure the impact of the program on a large scale. But anecdotal evidence attests to its life-saving benefits.

In 2019, Grand Chute police officer James Shepherd responded to a domestic disturbance call for a 19-year-old girl who was breaking items in her house. Shepherd was aware from previous police contact that the teen had a severe mental illness. When he arrived at her home, he opened the door and she lunged at him with a knife.

The knife struck his chest, but was deflected by his body armor, Grand Chute Police Chief Greg Peterson said.

“I mean, that is certainly a situation that would justify the use of deadly force to defend oneself. But in this instance, because the officer knew the young lady, had dealt with her previously, was aware of her mental health conditions, and was trained in the de-escalation techniques that are part of the CIT training, he immediately chose to disengage from her and begin backing away,” Peterson said.

Shepherd then retreated from the house to the garage, and spoke with the teen for about 30 minutes, using crisis negotiation tactics to try to get her to drop the knife and exit the house, Peterson said. Eventually, the Outagamie County emergency response team arrived and took the teen into custody.

“It was dramatically different than a very, I’ll say, traditional type of approach to a situation like that,” Peterson said.

Diverting people from the criminal justice system

CIT aims to not only help save lives, but also reduce criminalization of mental illness, Wallschlaeger said.

Wallschlaeger, who first became a police officer in 1994, worked in Hartland and Oshkosh before transferring to the Appleton Police Department in 2002, where he worked until his retirement in 2015. Early in his time as a police officer, Wallschlaeger noticed many police calls were for the same people, often struggling with homelessness, mental illness or substance abuse for minor incidents like trespassing or loitering. The traditional police approach of making arrests or issuing tickets in these situations was like a “revolving door,” he said; no matter how many calls to law enforcement were made, the same issues kept happening with the same people.

“That was one thing I learned in my career as I was young, as an officer. We weren’t fixing anything. We were just making that door spin,” Wallschlaeger said.

It’s an issue with policing that has grown in recent decades. Since widespread closings of mental health institutions across the United States in the mid-1970s, the primary group of people regularly interacting with those with serious mental illnesses has shifted from health care providers to police officers.

The problem with this, Wallschlaeger said, is most police officers are not trained in addressing mental health needs, and traditional policing methods often only add problems to a situation. As a result, the country’s criminal justice system has become flooded with people charged with crimes primarily for actions that stemmed from mental illness.

According to a 2020 NAMI study, about two in every five people incarcerated in jails and prisons in the United States have a history of mental illness. A report by the Treatment Advocacy Center states that in 2014, 383,000 people with severe mental illnesses were in jails and prisons in the United States — a population 10 times greater than those in state hospitals.

“If you call your doctor’s office, and they’re closed, what’s the common message that you hear on the phone? … ‘Call the police, go to the emergency room,'” Wallschlaeger said. “That system of care was defective, because it was directing people to the criminal justice system, which is not the best place to go. Because the criminal justice system is not very forgiving.”

Diverting mentally ill people away from the criminal justice system has benefits for everyone; treatment options in jails and prisons are limited, and housing people in jails and prisons for more than a couple months is more expensive than the cost of a stay at a hospital for inpatient treatment, studies show.

A quickly expanding program

Since its start in Appleton in 2004, CIT has spread to police departments and sheriff’s offices in close to half the counties in Wisconsin.

Since 2014, more than 3,350 officers in Wisconsin have received CIT training, and in the past year, more than 600 Wisconsin officers from 188 departments across 45 counties were trained, NAMI Wisconsin Program Director Emilie Smiley said.

NAMI Greater Milwaukee adapted a shortened version of CIT training for hospital staff around 2004. In 2007, Wallschlaeger and NAMI Fox Valley took that training concept and began offering it to community members and workers at all types of groups and agencies, like hospitals, jails, group homes and churches. They named it Crisis Intervention Partner training, or CIP. While CIT certification requires a five-day, 40-hour course, CIP certification takes just two days.

CIP grew rapidly. One of the first CIP trainings in 2007 involved people from Kenosha, Waushara, Waupaca, Manitowoc, Calumet, and Sheboygan counties, Wallschlaeger said.

Since then, NAMI Wisconsin has developed and continued bringing CIP training statewide. Representatives from the organization delivered a presentation on the training to leaders in other states at the annual CIT International Conference, held Aug. 14-16 in Detroit, Wallschlaeger said.

In Appleton, around half of the police department staff are trained in CIT, CIP or both. Of those in the patrol division, about 75% are CIT certified, Appleton Police Lt. Meghan Cash said.

De-escalation tactics taught in CIT have made their way into regular law enforcement training as well, particularly in the last four or five years, Peterson said.

CIT is intended to be a voluntary program for police officers. When officers “self-select” to get certified in CIT, they tend to be better suited for the program than officers who were certified merely as a mandatory part of training, Wallshlaeger said.

This may be partly because officers who choose to undergo CIT training often have a loved one with mental illness. Additionally, officers fresh out of the police academy may not be able to relate to the concept of a person facing a mental health crisis until they’ve encountered it firsthand, Wallshlaeger said.

CIT International has published a position statement about the importance of CIT being voluntary, which Wallshlaeger, who was on the CIT International board from 2017 through 2022, helped write.

“While CIT International fully supports all officers receiving robust generalist training in mental health awareness and de-escalation, mandated CIT training blurs the specialist component of the CIT model and has not worked well in some cities that have adopted this approach,” the statement reads.

In 2014, a Milwaukee police officer killed Dontre Hamilton, a man with schizophrenia who was sleeping in a park. The officer had unlawfully patted him down and in the ensuing scuffle shot him 14 times. The Milwaukee Police Department began requiring all officers to get trained in CIT, a three-year-long and $1.2 million undertaking.

Results found it may have further damaged relationships between law enforcement and the community by giving a specialist title to officers not sufficiently dedicated.

“Sometimes the city or or law enforcement administrators will simply do it for insurance purposes, for liability purposes. They think that that’s the save-all and it’s not,” Wallshlaeger said.

RELATED:In Milwaukee, $1.2 million police mental health training plan misses the mark

More than police work

The primary element of CIT and CIP is not merely training, but the creation of a collaborative network between law enforcement and mental health partners in the community.

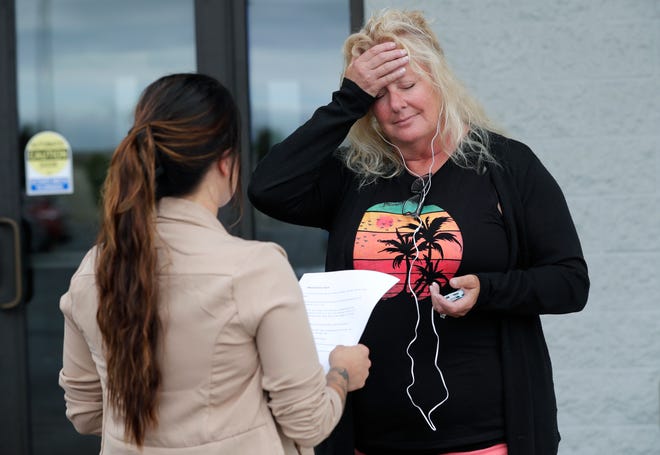

At a CIP training in late July, a class of 36 people gathered in a conference room at Catalpa Health in Appleton. Much of the training focused on developing empathy and gaining a better understanding of the struggles and experiences of people with mental illness.

For one activity, the “Hearing Voices Simulation,” trainees each took an MP3 player and set of earbuds and were tasked with completing different activities while listening to a recording that simulated auditory hallucinations a person with schizophrenia might hear. Activities included acting as a candidate in a simulated job interview, completing word searches and math problems under a time limit and following instructions to fold origami.

When members of law enforcement go through CIT training, the auditory hallucination simulation portion involves more tasks related to policing, said Josh Hopkins, behavioral health investigator at the Outagamie County Sheriff’s Office. CIT trainees are tasked with recalling license plate numbers and writing police reports, all while listening to the auditory hallucinations, which include repeated words and phrases, vulgar language and negative self-talk.

Hopkins said the purpose of the simulation is to help people get a better understanding of the added challenges people who experience auditory hallucinations have in their day-to-day lives.

Other parts of the July training similarly gave participants glimpses into others’ struggles. During one presentation, a video showed a depiction of what an overload of sensory input might look and sound like to an autistic person. Another presentation focused on adverse childhood experiences and was delivered by a father and his adult daughter. She was adopted as a child from Poland, and experienced run-ins with law enforcement growing up due to behavioral issues that stemmed from abuse she suffered in her youth.

A main focus of the training was breaking the stigma around mental illness. Being hospitalized or receiving treatment for a psychotic episode or clinical depression should be thought of no differently than receiving treatment for a broken bone, trainers said.

NAMI Fox Valley spearheads the CIT and CIP trainings in the Fox Valley area. While the organization serves Outagamie, Calumet, Waupaca and northern Winnebago counties, the trainings are open to others outside the area, said Megan Zimmerman, program outreach coordinator for NAMI Fox Valley.

Currently, NAMI Fox Valley holds one CIT training and two CIP trainings a year.

How CIT works

A person calling police can specifically ask for a CIT officer. When a CIT officer makes contact with someone experiencing a mental health crisis, they are taught to engage with a “nonviolent posture” and “use de-escalation techniques to allow that person to vent” before determining what their immediate needs are, Wallschlaeger said.

The officer then reaches out to community organizations — which among others can include NAMI Fox Valley; Catalpa, which offers psychiatric services for youth 18 and younger; SOAR, which has programming for people with developmental disabilities and traumatic brain injuries; and Brotoloc North, which has group homes for people with a variety of needs located in the Fox Valley — to see if they have they are familiar with that individual from previous contact. Often times, they are, Wallschlaeger said.

“Then, we might take them to a crisis center or someplace not the police department, and maybe not the emergency department, because neither one of those is going to be productive,” Wallschlaeger said.

Outagamie County has an eight-bed crisis center, Eastwood Crisis Facility, that can house people in crisis for less than 28 days. In Brown County, there is an 18-bed facility, while Winnebago County has a 16-bed crisis center. The crisis facilities are intended to help with stabilization, sometimes until someone can get inpatient care, or until they are stable enough to go home and continue outpatient therapy.

In Outagamie County, some calls have an added support. During his time working in behavioral health for the sheriff’s office, Hopkins has implemented the Safety Alert Flag Enrollment, or SAFE, Program. It allows community members with mental illness to voluntarily provide information about what they are like in a crisis state, giving first responders more context about what approach might be most helpful if they are called to respond to an incident.

“After the voluntary enrollment, I have an interview with them to try to gather information about their access to weapons, safety concerns that they have for themselves or others, description of behaviors and triggers, what their crisis looks like kind of, actions that first responders should avoid, actions that first responders can do to help, and family or friends that we can reach out to to get some additional information on,” Hopkins said.

Once that information is put into the system, officers have access to it before they get to the scene.

All law enforcement agencies in the county can refer people for the program, Hopkins said; 75 people are currently enrolled in it.

Limitations include barriers to CIT training at all law enforcement agencies

A major barrier to implementing CIT at smaller law enforcement agencies is that getting an officer certified requires they aren’t available for a week of work. For some police departments, that simply isn’t possible.

Zimmerman said many small departments opt instead for sending officers to the two-day CIP training, so they can at least receive some certification.

Law enforcement agencies looking to get officers trained can apply for grants, which are allocated statewide by NAMI Wisconsin. In 2014, the Wisconsin Legislature created a statute to support CIT and CIP that gives $250,000 every two years to expand and unify CIT and CIP programs across the state. In 2021, this amount was increased to $1 million. But these grants can only help with the cost, not the staffing shortage, Zimmerman said.

Hopkins said that while CIT is widespread across central and southern parts of Wisconsin, the program is rarer in many of the more rural northern communities.

There is also no required follow-up training or recertification. Even though CIT tactics have changed over the years, an officer who was CIT certified a decade ago is still certified today.

The statewide NAMI organization is working on piloting a follow-up CIT training in Wisconsin, which will start to roll out for trials in the next month or so, Zimmerman and Hopkins said. It will involve self-paced online learning, to be completed preferably three to five years after initial CIT certification.

“Mental health conditions are constantly changing, so our approach to addressing those mental health conditions should also constantly be changing,” Hopkins said.

Studies on CIT have tried to measure the program’s effectiveness. A 2019 report from the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law said studies have found that there is a lack of quantifiable data showing if CIT-trained officers use less force or are less likely to injure civilians or be injured themselves during interactions compared to non-CIT-trained officers. This may be partly due to a lack of large-scale studies on the topic, as well as underreporting of officer-involved shootings, the report said.

However, studies have found evidence that CIT has resulted in diverting people away from jail as well as improving attitudes among police officers, according to the report.

While CIT is one of the most widely implemented police programs for addressing mental health in the United States, there are other models that help prevent mentally ill people from getting deeply embedded in the criminal justice system or killed by police. These include co-responder teams, where a mental health worker responds to calls related to mental health crises alongside police officers, and mobile crisis units, where only mental health experts respond to a scene without law enforcement.

In Wisconsin, many law enforcement agencies use a combination of crisis response methods, Smiley said. Some departments, like Appleton, have CIT-trained officers as part of a co-responder team.

The Appleton Police Department implemented a co-responder model in January 2022, when it hired a clinical therapist. The therapist, Sarah Peterson, is available from 3 to 11 p.m. Monday through Friday to help community members who may be going through crisis during a police response.

Prior to the addition of the department therapist, however, police officers would sometimes have staff from Outagamie County Crisis respond to calls like welfare checks, Wallschlaeger said.

NAMI Wisconsin hosted its first Co-Responder Summit in June, which was attended by 12 teams from around the state, Smiley said. It led to the creation of NAMI Wisconsin Co-Responder Committee, which aims to track co-response efforts around the state.

“The ultimate response would be a mental health response without law enforcement,” Wallschlaeger said. “So that if somebody was in crisis, they could go to a 24/7 crisis facility without having law enforcement involved. That would be the ideal thing. Because when you talk about being overwhelmed by the crisis, having the cops there … maybe to transport them in a police car, that doesn’t make it better.”

However, Wallschlaeger said he recognizes crisis situations can sometimes pose dangers and require law enforcement officers who are trained in safety and de-escalation tactics.

Increasing beds at mental health facilities, which can have long waitlists, could also improve access to treatment for people experiencing mental health crises.

In Wisconsin, for a person to get hospitalized for mental health treatment, they must self-volunteer treatment and there must be a bed available — or, if there are no available beds, or a person is not willing to receive treatment during a crisis, a Chapter 51 commitment is required to get a person the help they need, Winnebago Mental Health Institute Deputy Director Maria Coonen explained at the July 25 CIP training session.

But under Wisconsin statues, a Chapter 51 commitment requires that a person has a treatable mental illness and is currently exhibiting suicidal or homicidal behavior. When that criteria isn’t met, a person in crisis might not be able to receive immediate treatment.

While there is no one perfect response, law enforcement entities continue to work to find ways to improve interactions with community members experiencing crises.

“I don’t think that we’ll ever be to a point where we can relax and say that we’ve done enough to address mental health,” Hopkins said. “I think it’s something that’s going to continue to evolve in the future, and it’s something that we need to continually be addressing and working through to continue to break that stigma, because it’s not going to go away on its own.”

Contact Kelli Arseneau at (920) 213-3721 or karseneau@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter at @ArseneauKelli.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.