For more than a decade, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has used the pretense of a counterterror campaign to wage a genocide against Chinese citizens who are members of Muslim-majority ethnic minority communities. This effort to eradicate the history, culture, and population of ethnic minorities in Western China has taken various forms: extrajudicial killings, forced sterilizations, forced abortions, sexual violence, mass detentions, and the destruction of cultural sites and places of worship (Human Rights Watch, 2021; Pompeo, 2021). This campaign has also coincided with the CCP’s industrial strategy of dominating the global supply chain for solar energy components. At their intersection, these two malign initiatives have given rise to the use of forced ethnic minority labor to manufacture solar components across a web of detention facilities.

In recent years, Congress has taken aggressive, bipartisan action to limit the infiltration into the United States of goods that are tainted by this modern slavery. Despite these efforts, multilateral organizations and development banks, such as the World Bank, continue to source solar components for international projects from companies with supply chains that pass through the epicenter of this ongoing genocide, Xinjiang. The United States is the largest contributor to the World Bank and, in recent years, the bank has agreed to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in solar projects across the world. Yet, the bank offers little public information about its safeguards—if they exist—against funding the products of forced labor in the solar supply chain.

This research report outlines the need for more rigorous congressional oversight of the World Bank to ensure that American taxpayer funds are not being used to purchase the products of a genocide. It begins with an outline of the CCP’s genocide of ethnic minorities in Western China, before detailing Congress’ efforts to limit the flow of goods tainted by forced labor into the United States. It then considers the World Bank’s current, loose regime for limiting the use of forced labor within its projects. It furthermore identifies two examples of World Bank–funded projects that source solar components from companies whose supply chains have been identified by international observers as potentially tainted by forced labor. It concludes with four policy proposals to exercise oversight of the World Bank and its safeguards against forced labor in the solar supply chains.

The Uyghur Archipelago of Repression

To enforce the state’s socialist ideology, the CCP uses repression to enforce conformity among people of faith. China’s northwesternmost region of Xinjiang has long been the site of such repression. The Muslim majority population of Xinjiang was first conquered by the Qing dynasty in the 18th century and has since largely remained under the authority of successive regimes in Beijing.[1] Following a series of violent agitations in opposition to the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC’s) rule, such as the riots in Urumqi in 2008 and the 2014 Kunming railway station attack in 2014, Xi Jinping inaugurated the so-called “Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism.” Unlike Western counter-terror initiatives, which focus on addressing the actions of individuals, the CCP’s Strike Hard campaign is distinct because of its use of repression against the breadth of the local Muslim community (Doyon, 2019). Those targeted in this campaign include a variety of ethnic minorities, such as the Uyghurs, Hui, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, and Uzbeks. This campaign has been recognized as a genocide by both the Trump and Biden administrations, as well as the Canadian (Gillies, 2021), Dutch (Schaart, 2021), and British parliaments (Piper, 2021).

This repression on a population-wide scale intensified beginning in August 2016, when the CCP committee secretary of the heavily repressed Tibet region, Chen Quanguo, assumed the role of committee secretary for Xinjiang (Wang, 2018). International observers estimate that about one million Chinese Muslims are being held in a web of up to 400 prisons, “re-education camps,” or pre-trial detention centers (Human Rights Watch, 2021). Individuals have reportedly been detained for wearing Islamic-style beards or headscarves (The Guardian, 2020). In addition to ideological indoctrination sessions, many of those detained are subject to forced labor in a variety of manufacturing industries under the guise of “vocational training” (U.S. Department of State, 2021).

The CCP’s forced labor facilities constitute a reincarnation of the Soviet Union’s tools of repression. To distinguish the CCP’s dogma from its Soviet counterpart, its ideology has been described as ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ since the era of dictator Deng Xiaoping. Like the Gulag archipelago of forced labor camps upon which dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn famously shone light, the CCP’s web of forced labor camps represents a Uyghur archipelago of repression.

The CCP’s willingness to employ forced Muslim labor intersects with its industrial policy to support its domestic solar power manufacturing industry (Chung et al., 2016). The Xinjiang Autonomous Region has become the epicenter of this coercive and destructive industrial strategy. Inmates across the CCP’s archipelago of detention camps have been forced, for little or no compensation, to produce the necessary inputs for manufacturing solar panels, which are then exported to foreign markets (U.S. Department of State, 2021). A key input is polysilicon, which is produced into the cells that form the panels. More than 50% of the PRC’s solar-grade polysilicon is produced in the Xinjiang region (U.S. Department of Labor, 2021), where coal-fired plants are used to produce the high levels of energy needed to transform quartz sand into polysilicon (Murtaugh et al., 2021). Additionally, the CCP has implemented a labor transfer program that sends coerced Muslim laborers to different provinces across China (Xu et al., 2020).

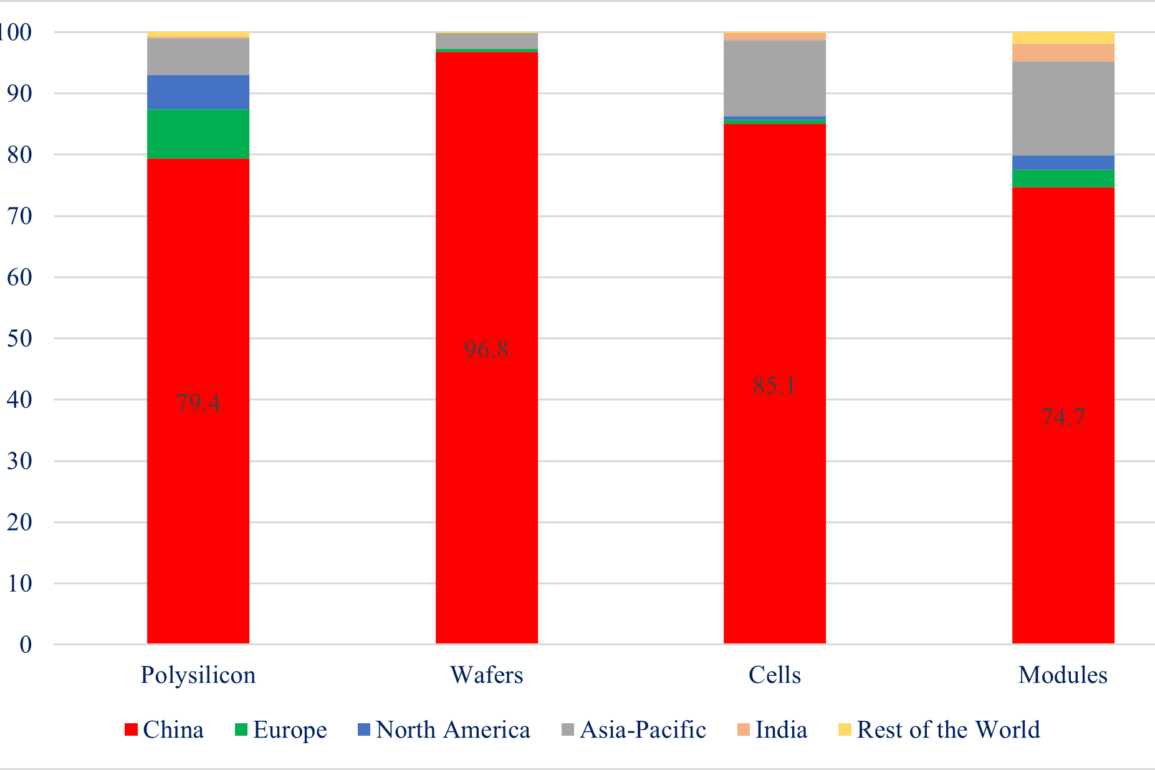

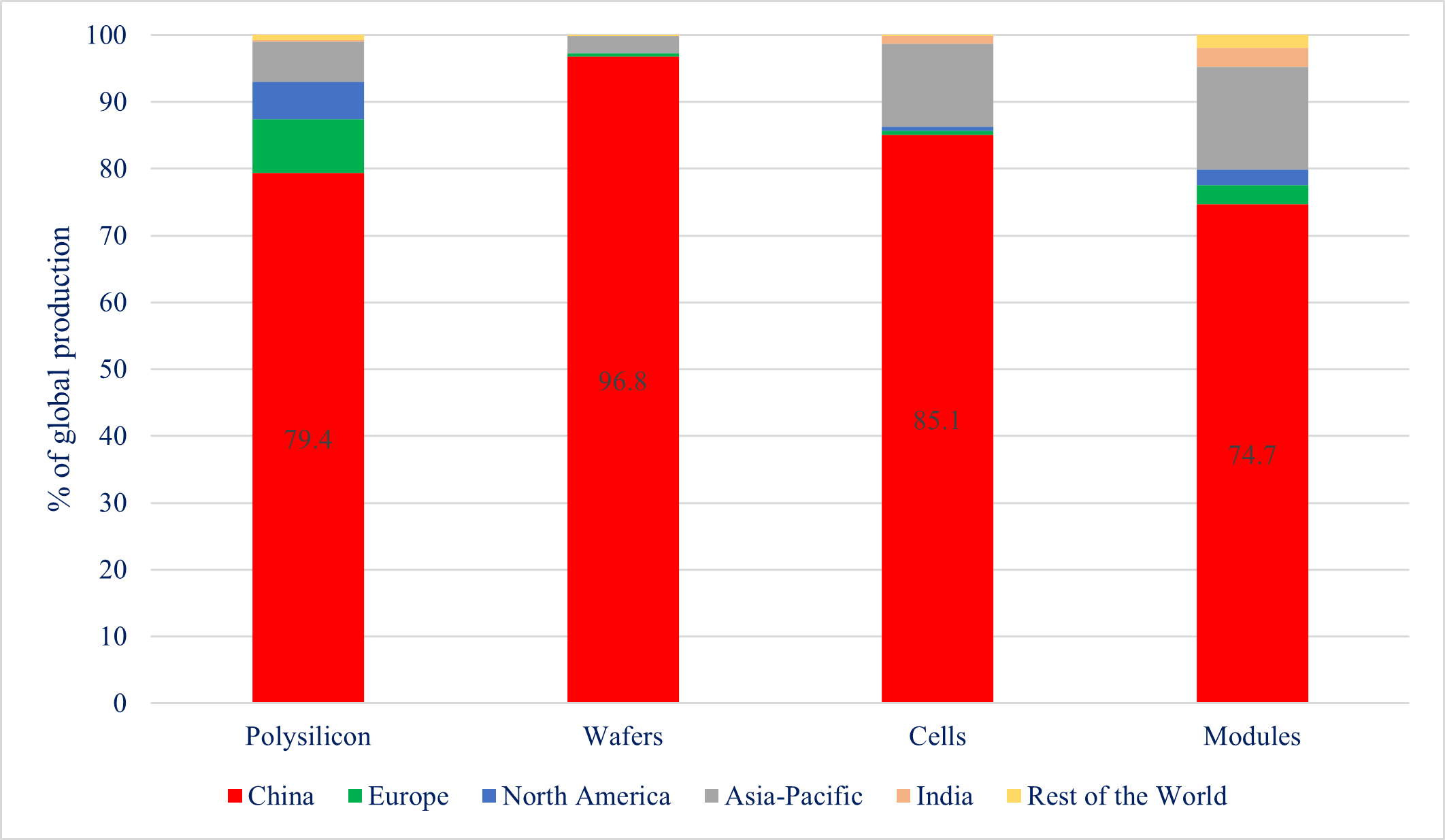

The manufacture of solar panels requires many steps. In brief, silica must be developed into polysilicon, which is then formed into wafers. These wafers are manufactured into solar cells, which are arranged into solar modules or panels. As figure 1 illustrates, the PRC is the dominant producer at each major stage of the solar manufacturing process. In aggregate, the PRC is the largest producer of solar panels and five of the world’s six largest solar manufacturers are based within the PRC (Santos, 2023).

Figure 1. Solar photovoltaic manufacturing capacity by country and region, 2021[2]

Protecting American Consumers

In recent years, the United States has taken a variety of measures to limit the importation of solar components that were likely produced with forced labor. In June 2021, consistent with its obligations under the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA), the Department of Labor’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs formally listed polysilicon produced in China as a product of forced labor (U.S. Department of Labor, 2021). This designation serves to inform U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP’s) exercise of its duty to detain shipments when their goods or inputs are suspected to be the product of forced labor.[3]

Later that June, the Commerce Department added several Chinese solar component manufacturers to its Entity List because of their use of forced labor in Xinjiang (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2021). Additions are made to this list by an interagency End-User Review Committee—with representatives from the Departments of Commerce, State, Defense, Energy, and, when appropriate, Treasury—“if specific and articulable facts provided reasonable cause to believe that the entity is involved in, has been involved in, or poses a significant risk of being or becoming involved in…activities that are contrary to U.S. national security or foreign policy interests” (Authorization To Impose License Requirements for Exports or Reexports to Entities Acting Contrary to the National Security or Foreign Policy Interests of the United States, 2008, p.49312). Their designation restricts the manufacturers’ ability to purchase a range of American commodities, software, and technologies without a license (Addition of Certain Entities to the Entity List, 2021).

That was followed by the Department of Homeland Security’s issue of a withhold release order (WRO) for silica-based products made by Hoshine Silicon Industry Co. Ltd. (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2021). The WRO established a rebuttable presumption that these products were inadmissible to the United States because of their likely manufacture through forced labor in the Xinjiang region.

This WRO was superseded by the bipartisan Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), which came into force on June 21, 2022. The UFLPA similarly establishes a rebuttable presumption that all goods or inputs mined, produced, or manufactured in the Xinjiang region are inadmissible due to their likely use of forced labor. It also creates a unique Entity List for companies outside of the Xinjiang region that nonetheless use forced labor or inputs made by forced labor, and thus their products are presumed to be inadmissible to the United States. Twenty companies were initially placed on the UFLPA Entity List. In June 2023, two more companies were added, while another two were added in August 2023 (Egan et al., 2023).

While the UFLPA constitutes an important step toward restricting the traffic of goods that are tainted by forced labor in Xinjiang, it is not a panacea. In a letter to Department of Homeland Security Under Secretary Robert Silvers, the co-chairs of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China— Representative Christopher H. Smith (R-NJ) and Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR)—identified the UFLPA’s shortcomings (Congressional-Executive Commission on China, 2023). They note that CBP has detained hundreds of shipments of goods, only to release them into the United States “because the importer claimed—and CBP accepted—that the UFLPA didn’t apply. The goods released included items from high-risk sectors with significant ties to the XUAR [Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region] and labor transfer programs.” The co-chairs highlight that the UFLPA Entity List is insufficiently broad and that the de minimis rule—which allows senders to list minimal information on packages worth less than $800—inhibits the enforcement of the UFLPA.[4]

The International Loophole

The United States’ efforts to limit the proliferation of goods made through slave labor in the PRC, unfortunately, are not replicated across the globe. As the co-chairs of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China note, the shipment of components or goods likely tainted by slave labor in Xinjiang through third countries before they reach the United States—known as ‘transshipment’—is a serious enforcement challenge (Congressional-Executive Commission on China, 2023). For example, of the shipments denied entry to the United States under the UFLPA, only 31% were sent directly from the PRC.[5] By contrast, 43% originated from Vietnam and 23% from Malaysia. The global spread of these goods is likely exacerbated by efforts to support the expansion of solar power facilities without sufficient oversight of the origins of their components.

In recent years, multi-lateral development banks (MDBs), such as the World Bank, have dedicated hundreds of millions of dollars to supporting solar energy generation in developing countries, albeit without rigorous anti–forced labor safeguards.[6]

The World Bank has established eight contractually binding performance standards to regulate environmental and social conditions within bank-funded projects. These standards include a prohibition on forced labor or coercive child labor within projects, with little scrutiny of how project inputs—such as industrial or solar components—are manufactured. The feebleness of the World Bank’s due diligence procedures was underscored in April 2022, when an international team of researchers published evidence that the bank, through its International Finance Corporation (IFC), had made loans or equity investments in four companies that were likely participating in the repression of Chinese Muslims in Xinjiang (Murphy et al., 2022).

The World Bank (2023b) has acknowledged that there is “a significant risk of forced labor in the global supply chain for solar panels and solar components.” Yet, the bank’s effort to prevent the funding of forced labor within the solar supply chain is limited to a series of self-declaration forms and contractual terms forbidding their use (World Bank, 2023a). Meanwhile, the CCP has dismissed the overwhelming evidence of forced labor as baseless (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China, 2021). Similarly, Xinjiang East Hope Nonferrous Metals Co., Ltd. reportedly rebuked its designation on the UFLPA Entity List as “a lie and a groundless slander” (Tianshannet, 2020). It is thus extremely unlikely that products made through forced labor within the solar supply chain will be consistently excluded from World Bank projects.

Rather than echoing the bipartisan consensus behind the UFLPA and moderating the World Bank’s myopic approach, the Biden Administration has sought to further the global expansion of solar generation, without further efforts to limit the proliferation of forced labor. In August 2021, the U.S. Treasury Department issued its Guidance on Fossil Fuel Energy at the Multilateral Development Banks, which outlines the Biden Administration’s approach to energy projects that are facilitated by MDBs (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2021). This guidance dictates that the United States will generally oppose direct investment in coal, oil, and upstream natural gas projects, while considering fossil fuel projects only when they are the last resort. The United States’ influence over the World Bank is immense. With $3.5 billion in paid-in capital and $47.8 billion in callable guarantees, the United States is the largest single shareholder in the World Bank.[7]

Furthermore, over the past decade, the United States contributed on average at least an additional $1 billion each year toward low interest loans and grants through the World Bank’s subsidiary, the International Development Association (Congressional Research Service, 2023, p.2). Commensurate with the United States’ preeminent role in the World Bank, the president of the bank is traditionally an American or dual citizen who is appointed by the United States.

A Trail of Repression

Tracing international supply chains of solar panels—especially from within the PRC—is notoriously difficult. According to a recent report on mapping the supply of forced labor products, “information regarding solar industry sourcing is becoming less transparent over time, thwarting the world’s ability to source ethically” (Crawford et al., 2023, p. 2). Nonetheless, it is possible to identify solar energy projects that the World Bank financially supports and to examine the contractors and suppliers of solar components, with a focus on whether their products have previously been labeled as potentially tainted by forced labor. In contrast with the rigorous nature of the UFLPA and the transparency of its enforcement, the World Bank’s lack of rigorous guardrails against the infiltration of goods tainted by forced labor, and the opacity of the World Bank’s procurement process, underscores the need for further congressional oversight of the World Bank and its project financing.

Recent efforts by the bank to expand solar generation in the Central African Republic (CAR) illustrate the need for further oversight. In 2019, the World Bank announced that it had approved a $48 million grant, through the International Development Association, for the construction of a 25-megawatt (MW) solar photovoltaic power plant near the CAR’s capital, Bangui (World Bank, 2019). In July 2023, JinkoSolar—one of the PRC’s largest solar manufacturers—announced that it had provided solar modules for the project. According to the announcement, “This project marks JinkoSolar’s participation in its first World Bank Loan project in the Central and Western Africa region” (JinkoSolar, 2023).

It remains unclear whether the solar components in the Bangui project were the product of forced labor. While JinkoSolar has reportedly sought to develop dedicated supply chains for the American market that comply with the UFLPA, the exact progression of its inputs and products through each stage of development is opaque. The least clear step of the process is the upstream mining of quartz and its production into metallurgical grade silicon, which is then made into polysilicon. The PRC’s silicon production capacity is centered in Xinjiang (Shanghai Metals Market, 2023). As Crawford et al. (2023, p. 19) highlight, “Jinko only provides information about purchased polysilicon on a global basis, so it is not possible to ascertain where precisely the company’s purchased polysilicon is consumed…Without further disclosures, it is not possible to exclude XUAR [Xinjiang] exposure in any of Jinko’s supply chains.” Consistent with the World Bank’s (2023b) recognition of “a significant risk of forced labor” in the global solar supply chain, without rigorous oversight of the Bangui solar project’s procurement process, there is a significant risk that World Bank resources—and, consequently, American taxpayer dollars—have been used to buy goods that are the product of forced labor.

A similar example is the 500 MW Abydos solar project in Egypt’s Aswan governorate. In November 2022, the IFC approved $105 million in financing to support what is set to become one of Africa’s largest solar projects (International Finance Corporation, 2022). While the project would be developed by the Emirati company AMEA Power, it was widely reported that the Chinese solar manufacturer JA Solar would provide its Deep Blue 3.0 Pro solar modules for the project (Bhambhani, 2023; JA Solar Technology Co., Ltd., 2023; Jacobo, 2023). Yet, according to Crawford et al. (2023, p.14), JA Solar publicly discloses that it sources some of its polysilicon from Xinjiang under contracts that run until at least December 2026. Coupled with the opacity of JA Solar’s supply chains, these contracts lead Crawford et al. (2023, p.15) to conclude that there is a very high risk that “all modules produced by JA Solar” have some exposure to the Xinjiang region. Although the project has received financial support from the IFC, of which the United States is the largest shareholder, these solar modules would be inadmissible to the United States without proof that their polysilicon inputs are not the product of forced labor.

Policy Recommendations

The primary victims of the CCP’s repression are the civilians living within the PRC’s borders. A prominent example of this repression is the ongoing genocide of Muslim-majority ethnic minorities in Western China, such as the Uyghurs, many of whom have been subject to forced labor and modern slavery. In recent years, Congress has taken overwhelmingly bipartisan steps toward limiting the infiltration of the products of forced labor into the United States. Despite these commendable efforts, due to the PRC’s domination of global solar manufacturing supply chains, there is a significant risk that American taxpayer dollars are funding an integral tool of the CCP’s ongoing genocide of ethnic minorities. The following actions can establish public confidence that taxpayer funds are not being egregiously misused:

- Immediately repeal the Treasury Department’s Guidance on Fossil Fuel Energy at the Multilateral Development Banks, which prioritizes energy projects that are potentially tainted by forced labor in the absence of rigorous oversight.

- Conduct congressional oversight of the United States’ participation in multilateral development banks, such as the World Bank, and other relevant organizations that receive American taxpayer funds, such as the United Nations and its associated agencies. For example, congressional testimonies by the Under Secretary of the Treasury for International Affairs and United States Executive Director of the World Bank would help to elucidate current efforts—if any—to further limit the World Bank’s procurement of solar components tainted by slave labor. Moreover, requesting detailed, written ‘questions for the record’ from witnesses after a live hearing would allow for the presentation of details not readily available in a hearing setting.

- Legislatively mandate a study of the World Bank’s financial support for international solar projects and the bank’s past and current safeguards against procuring goods or inputs tainted by forced labor. The secretary of the treasury, in consultation with the secretary of state, would be well placed to submit an unclassified study to the appropriate House and Senate committees on this issue. A study would further outline the nature of the World Bank’s efforts to limit the proliferation of goods made with forced labor, as well as potential opportunities for further oversight.

- Withhold financial support for multilateral development banks, organizations, or agencies that cannot demonstrate sufficiently rigorous safeguards against procuring goods or inputs that are tainted by forced labor.

While these policies will not guarantee a conclusive end to the genocide in Western China, they will nonetheless align the United States’ participation in the World Bank with domestic, bipartisan efforts to inhibit the traffic of components and goods that are the product of this genocide.

[1] The First and Second East Turkestan Republics are notable exceptions.

[2] Data from the International Energy Agency (2022).

[3] Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. § 1307).

[4] Section 321 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. § 1321).

[5] Data from June 2021 to July 2023 See: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/trade/uyghur-forced-labor-prevention-act-statistics.

[6] Project-level data on loans and grants made by the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation can be found at https://disclosures.ifc.org/.

[7] These resources are dedicated to the World Bank’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). The bank includes five separate arms: the aforementioned IBRD, the International Development Association, the International Finance Corporation, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.

Works Cited:

Addition of Certain Entities to the Entity List. 86 Fed. Reg. 33119 (June 24, 2021) (to be codified at 15 C.F.R. 744). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/06/24/2021-13395/addition-of-certain-entities-to-the-entity-list

Authorization To Impose License Requirements for Exports or Reexports to Entities Acting Contrary to the National Security or Foreign Policy Interests of the United States. 73 Fed. Reg. 49311 (August 21, 2008) (to be codified at 15 C.F.R. pts. 730, 744, 756). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2008/08/21/E8-19102/authorization-to-impose-license-requirements-for-exports-or-reexports-to-entities-acting-contrary-to

Bhambhani, A. (2023, January 6). Ground Breaks for 560 MW Kom Obo Abydos Solar PV Project in Egypt With JA Solar Modules, To Produce Clean Electricity At $0.02/KWh. Taiyang News. https://taiyangnews.info/markets/africas-largest-solar-plant-enters-construction-in-egypt/.

Chung, D., Horowitz, K., and Kurup, P. (2016). Emerging Opportunities and Challenges in U.S Solar Manufacturing. U.S Department of Energy, National Renewable Energy Laboratory. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy16osti/65788.pdf.

Congressional-Executive Commission on China (2023, May 3). Bipartisan Group of Lawmakers Seeks Answers from Administration About Enforcement of Forced Labor Legislation

[Press release]. https://www.cecc.gov/media-center/press-releases/bipartisan-group-of-lawmakers-seeks-answers-from-administration-about.

Congressional Research Service (2023, May 1). The World Bank. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/2023-05-01_IF11361_660fa30baecf4092d069adf6bc3e8ce0ea856dbf.pdf.

Crawford, A. and Murphy, L. T. (2023). OVEREXPOSED: Uyghur Region Exposure Assessment for Solar Industry Sourcing. Helena Kennedy Center for International Justice, Sheffield Hallam University. https://www.shu.ac.uk/helena-kennedy-centre-international-justice/research-and-projects/all-projects/over-exposed.

Doyon, J. (2019, January 14). ‘Counter-Extremism’ in Xinjiang: Understanding China’s Community-Focused Counter-Terrorism Tactics. War on the Rocks. https://warontherocks.com/2019/01/counter-extremism-in-xinjiang-understanding-chinas-community-focused-counter-terrorism-tactics/.

Egan, B.J., Fisch, E. J., Leiter, M.E., Allen, B.E., Floyd, S. A., and Kimbrell, N. (2023). US Government Updates Forced Labor Strategy, Expands UFLPA Entity List. Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP. https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2023/08/us-government-updates-forced-labor-strategy.

Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America (2021, July 8). The 12th Press Conference by Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region on Xinjiang-related Issues in Beijing [Press release]. http://us.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/zt_120777/dmxj/xjfabuhui/xjfbh12/202107/t20210724_9039382.htm.

Gillies, R. (2021). Canada’s Trudeau, Cabinet Abstain from China Genocide Vote. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/race-and-ethnicity-cabinets-justin-trudeau-china-olympic-games-5c85eedb0d3c3811ba1fd56eb4ac325d.

The Guardian (2020, February 17). China Detains Uighurs for Growing Beards or Visiting Foreign Websites, Leak Reveals. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/18/china-detains-uighurs-for-growing-beards-or-visiting-foreign-websites-leak-reveals.

Human Rights Watch (2021, April 19). “Break Their Lineage, Break Their Roots”: China’s Crimes against Humanity Targeting Uyghurs and Other Turkic Muslims. https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/19/break-their-lineage-break-their-roots/chinas-crimes-against-humanity-targeting

International Energy Agency (2022, July). Special Report on Solar PV Global Supply Chains. https://www.iea.org/reports/solar-pv-global-supply-chains.

International Finance Corporation (2022). Abydos Solar IPP. https://disclosures.ifc.org/project-detail/SII/41727/abydos-solar-ipp.

JA Solar Technology Co., Ltd. (2023, January 17). Ja Solar to Supply All High-Efficiency Modules for Egypt’s Largest PV Project. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ja-solar-to-supply-all-high-efficiency-modules-for-egypts-largest-pv-project-301723025.html.

Jacobo, J. T. (2023, January 17). JA Solar to Supply Modules to 560MW Solar PV Project in Egypt. PV Tech. https://www.pv-tech.org/ja-solar-to-supply-modules-to-egypts-largest-solar-pv-project-560mw-capacity/.

JinkoSolar (2023, July 3). JinkoSolar Empowers 25MW PV Project in Central Africa Republic, Supporting World Bank’s “Light Up Africa” Initiative. https://www.jinkosolar.com/en/site/newsdetail/1947.

Murphy, L. T., Salcito, K., and Elimä, N. (2022). Financing & Genocide: Development Finance and the Crisis in the Uyghur Region. Sheffield Hallam University, Helena Kennedy Centre (February 2022). https://www.shu.ac.uk/helena-kennedy-centre-international-justice/research-and-projects/all-projects/financing-and-genocide.

Murtaugh, D., Murphy, C., and Mayger, J. (2021, April 13). Secrecy and Abuse Claims Haunt China’s Solar Factories in Xinjiang. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-xinjiang-solar/?sref=ojq9DljU.

Piper, E. (2021, April 22). UK Parliament Declares Genocide in China’s Xinjiang; Beijing Condemns Move. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/uk-parliament-declares-genocide-chinas-xinjiang-raises-pressure-johnson-2021-04-22/.

Pompeo, M. R. (2021, January 19). Determination of the Secretary of State on Atrocities in Xinjiang. U.S. Department of State. https://2017-2021.state.gov/determination-of-the-secretary-of-state-on-atrocities-in-xinjiang/

Santos, B. (2023, April 13). Top PV module manufacturers by shipment volume in 2022. PV Magazine. https://www.pv-magazine.com/2023/04/13/top-pv-module-manufacturers-by-shipment-volume-in-2022/.

Schaart, E. (2021, February 25). Dutch Parliament Declares Chinese Treatment of Uighurs a ‘Genocide.’ Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/dutch-parliament-declares-chinese-treatment-of-uighurs-as-genocide/.

Shanghai Metals Market (2023, February 6). Everything You Need to Know About China’s Industrial Silicon Market. https://news.metal.com/newscontent/102084821/Everything-You-Need-to-Know-about-China%E2%80%99s-Industrial-Silicon-Market/.

Tianshannet (2020, July 15). A Solemn Statement from Xinjiang East Hope Nonferrous Metals Co., Ltd. Against Unjustifiable Sanctions by the United States. http://english.ts.cn/system/2021/07/15/036661265.shtml.

U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Public Affairs (2021, June 24). Commerce Department Adds Five Chinese Entities to the Entity List for Participating in China’s Campaign of Forced Labor Against Muslims in Xinjiang [Press release]. https://www.commerce.gov/news/press-releases/2021/06/commerce-department-adds-five-chinese-entities-entity-list.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (2021, June 24). The Department of Homeland Security Issues Withold Release Order on Silica-Based Products Made by Forced Labor in Xinjiang [Press release]. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/department-homeland-security-issues-withhold-release-order-silica.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of International Labor Affairs (2021). Against Their Will: The Situation in Xinjiang. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/against-their-will-the-situation-in-xinjiang.

U.S. Department of State, Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (2021, July 1). Forced Labor in China’s Xinjiang Region [Press release]. https://www.state.gov/forced-labor-in-chinas-xinjiang-region/.

U.S. Department of the Treasury (2021, August 16). Treasury Announces Fossil Fuel Energy Guidance for Multilateral Development Banks. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0323.

Wang, M. (2018). “Eradicating Ideological Viruses”: China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/09/10/eradicating-ideological-viruses/chinas-campaign-repression-against-xinjiangs.

World Bank (2019, February 14). Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Grant in the Amount of SDR 46.8 Million (US $65.0 Million Equivalent) to the Central African Republic for the Emergency Supply and Access Project (Puracel). https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/307711551668592488/pdf/SIERRA-LEONE-PAD-02192019-636872473755315841.pdf.

World Bank (2023a). Procurement Framework for IPF Projects – For Projects After July 1, 2016. https://www.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/products-and-services/brief/procurement-new-framework.

World Bank (2023b). Project Procurement – Policies, Guidelines, Documents for Projects Before July 2016. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/products-and-services/brief/procurement-policies-and-guidance.

Xu, V. X.; Cave, D.; Leibold, J.; Munro, K.; and Ruser, N. (2020, March 1). Uyghurs for sale: ‘Re-education’, forced labour and surveillance beyond Xinjiang. Australian Strategic Policy Institute, International Cyber Policy Centre. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/uyghurs-sale.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.