Alabama Department of Corrections Commissioner John Hamm said Tuesday the agency has a net gain of almost 250 security employees since a substantial pay raise last year.

In a presentation to state lawmakers, Hamm said the ADOC went from 1,705 full-time correctional officers and security staff in April 2023 to 1,953 in June 2024. That reversed a trend of declining employee numbers in the state’s overcrowded prisons that U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson said had “horrendous understaffing.”

But Hamm said the ADOC is unlikely to meet a federal court order to add about 2,000 more officers by mid-2025. That order is part of a federal lawsuit over mental health care in prisons, a case that’s been going on since 2014.

“It’s a tough job,” Hamm said. “We’re not attracting folks that want something easy, a 9 to 5 job.”

The ADOC generally has about 55 candidates in its 10-week correctional officer training academy, Hamm said. There are four sessions per year. The ADOC can also count correctional security guards, who go through a six-week course, toward the staffing goal. But it still appears to be well out of reach.

Even so, Hamm said he believes the ADOC can show the court it is making a good-faith effort.

Hamm, picked by Gov. Kay Ivey to lead a troubled prison system starting in January 2022, said increasing the number of correctional officers is a fundamental part of fixing problems identified in federal litigation against the prison system, including the mental health case and a lawsuit filed by the U.S. Department of Justice in 2020 that alleges the violent conditions in Alabama’s men’s prisons violates the constitution.

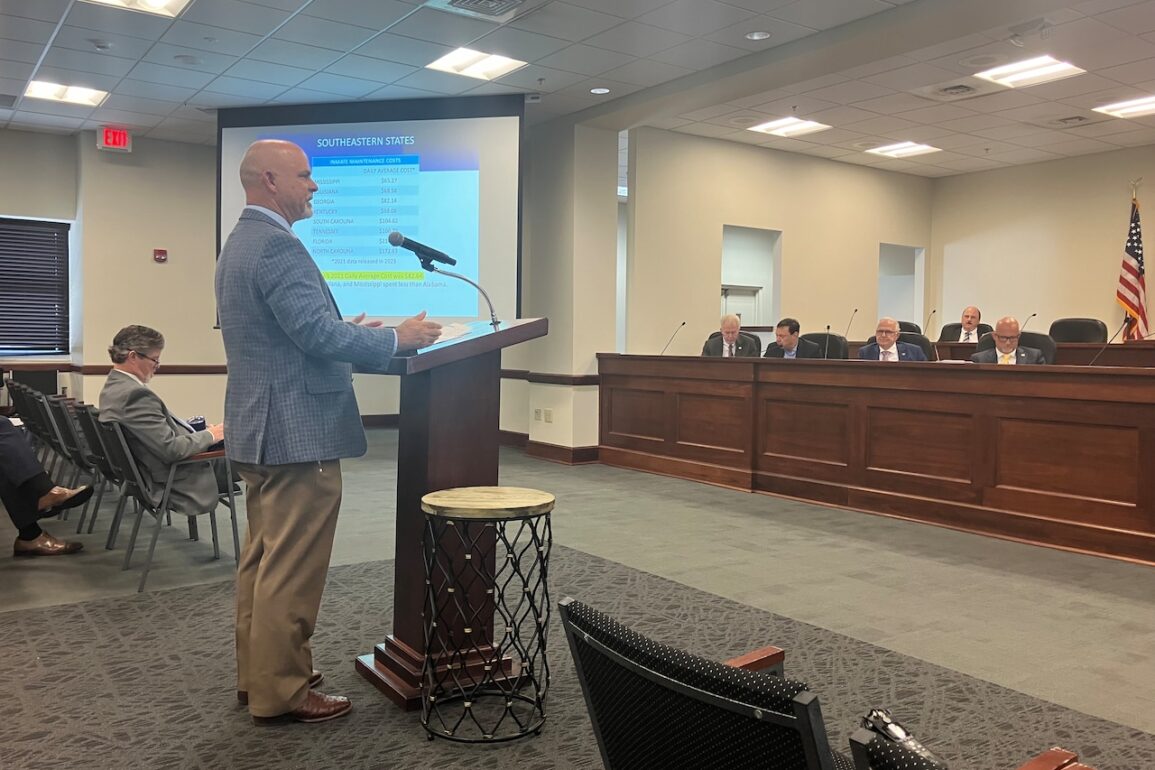

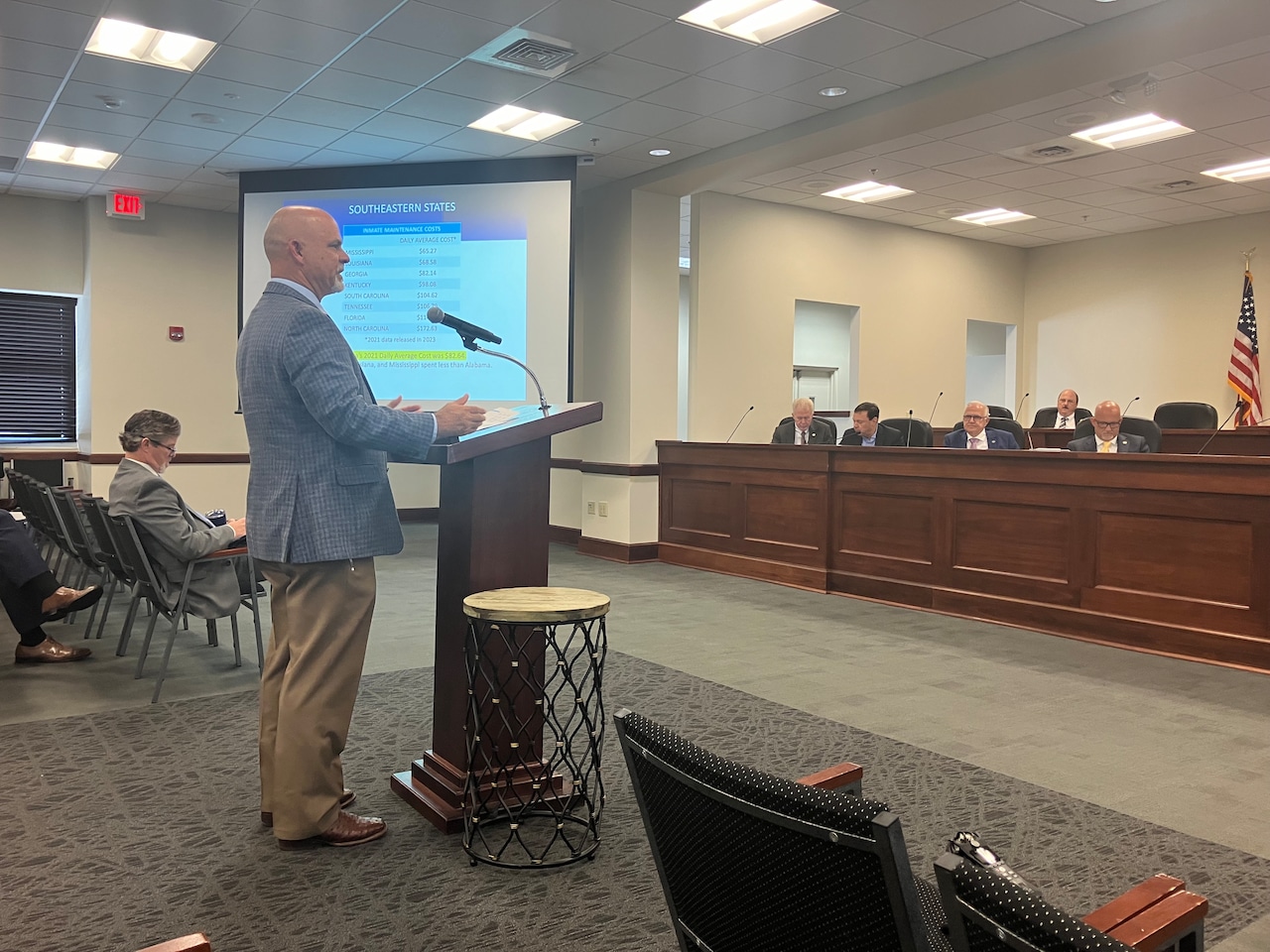

Hamm spoke to members of the Legislature’s budget committees during an informal budget hearing.

ADOC’s new pay scale that started last year raised the pay of correctional officer trainees who complete the academy to slightly more than $50,000, with a chance to hit about $65,000 after 18 months or up to about $71,000 if they work at a maximum security prison.

The purpose was to help ADOC compete with police and sheriff’s departments for law enforcement candidates.

“The pay raise seems to have had a major effect,” Sen. Greg Albritton, R-Atmore, chairman of the Senate’s General Fund Committee, told Hamm.

Hamm agreed, but also cited some of the factors that make it hard to hire correctional officers despite more emphasis on recruiting.

Hamm said ADOC has held 76 hiring events this year that have attracted 1,191 job candidates. But he said less than half – only 453 – passed a physical fitness test required to become a correctional officer.

Hamm said the test is a modified version of the physical agility, physical ability test developed by the Alabama Peace Officers Standards and Training Commission (APOSTC).

The test includes pushing a sled, running, stepping over and moving under hurdles, crossing a balance beam, completing a 300-memter sprint and other challenges.

Candidates who fail the test can still go on to work as a correctional security guard, but that means more limited responsibilities than a correctional officer.

Hamm said ADOC has some candidates for correctional officer jobs eliminated because they have gang affiliations.

“That’s just some of the reality of what happens in the Department of Corrections,” Hamm said.

Hamm said the agency is open to suggestions on how to further increase the staffing numbers.

“We’re all ears at Corrections about hiring good people to be correctional officers,” he said.

Albritton said lawmakers have been trying to help with the staffing shortage for years, including a program created in 2019 that paid bonuses to help keep correctional officers on the job.

“I appreciate the trend,” Albritton said. “We’ve got a long way to go.”

Hamm also gave lawmakers an update on prison construction. Three years ago, Alabama lawmakers approved a plan to build two 4,000 bed men’s prisons for $1.3 billion. As it turned out, that was only enough money for the first of the two prisons.

Hamm said the prison in Elmore County, with a construction cost of $1.1 billion, is on track for completion in May 2026. He said adding the equipment and furnishings necessary to operate the prison would raise the project cost to $1.25 billion. The prison has special facilities for medical and mental health care.

The Elmore County prison was originally estimated to cost $623 million. Officials blamed the cost increase on inflation, design changes made to accommodate court orders, and other factors affecting construction projects.

As for the second prison, planned for Escambia County, Hamm said negotiations are ongoing with a company to design the facility, but that no contract has been signed and there is no projected start date.

Hamm said the money is in hand to finish the Elmore County facility. But lawmakers have not approved all the funding necessary for the Escambia prison.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.