Letters written to support and resist: On the last Thursday of each month, a few dozen Muscovites gather in the heart of Moscow, in a room at the headquarters of Yabloko – the liberal party inherited from the 1990s, and still going – to write postcards to political prisoners. On the tables, among the photos and names of those behind bars, a few famous inmates’ faces stand out.

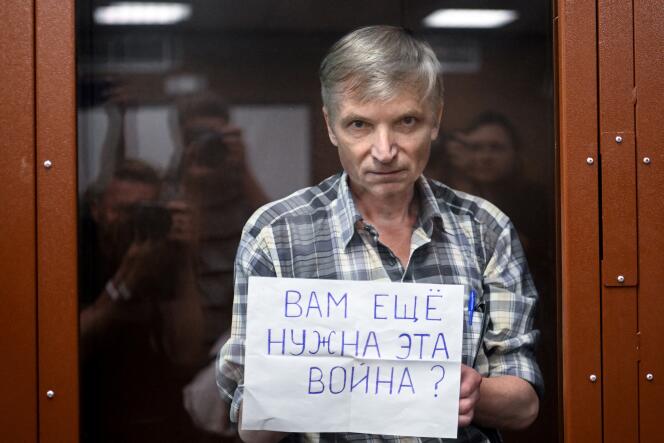

More than two and a half years after the start of the Kremlin’s “special operation” in Ukraine, most of the Russians arrested for their opposition to the military offensive and President Vladimir Putin’s regime are anonymous citizens. “More than 700! Caught up in the crushing machine of our justice system. We must not forget them,” insisted Anna Shatunovskaya, organizer of these “postcard” evenings.

On August 1, Russia and the West exchanged 26 of their nationals (24 adults and two children), the largest prisoner swap since the end of the Cold War. In exchange for an agent convicted of murder in Germany and a couple of spies arrested in Slovenia, the West obtained the release of Americans, including Evan Gershkovich, Moscow correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, as well as several Russian opposition figures such as politicians Vladimir Kara-Murza and Ilya Yashin, human rights activist Oleg Orlov, activists Lilia Chanysheva and Ksenia Fadeyeva, and artist Aleksandra Skochilenko. These names and faces have long been on the tables at Yabloko. Every Thursday evening, ordinary Muscovites would come to write them postcards.

A month after the exchange, the ritual has continued. “Some have been released. But there are still all the others… It’s impossible to remain inactive, like the majority of Russians! It’s our way of supporting dissidents and, in the face of the Kremlin, of resisting,” said Olga, one of the volunteers Le Monde met on Thursday, August 29. Like the others, she preferred to remain anonymous, a precaution in the face of growing repression against all critical voices.

“It’s good to be in this room again. We don’t feel alone,” said the mother in her 40s. That evening, from students to grandmothers, nearly 50 people methodically wrote and signed postcards. On one Thursday, they even exceeded 100 participants. Pro-Kremlin provocateurs intervened one time, leading to police intervention.

Banal words about life

The organizers are not immune from a new round of bans on these perfectly legal sessions of indirect opposition, which “are one of the last possible ways of expressing a ‘no’ to the war and the regime,” said Irina, a student. “It’s not yet forbidden to write to dissidents!” In her letters, among the 300 or so sent that evening, there were no political statements that would have been censored by the prison administration, just banal words about life.

You have 53.47% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.