A U.S. soldier kills a German citizen on German soil and confesses afterwards. A U.S. military court acquits him anyway, but why? LTO investigations reveal that German police is in part to blame.

Hier geht es zur deutschen Version des Artikels.

It was a mild summer evening in Wittlich, Rhineland-Palatinate on August 18, 2023. People were out in the town enjoying the yearly Säubrenner fair, among them Michael Ovsjannikov. But only a few hours later, he was fatally stabbed following an argument with a U.S. soldier. His death and the subsequent trial caused outrage far beyond Wittlich, sparking a public debate not only about judicial double standards on German soil, but the very foundations of the German rule of law.

At first, it seemed to be an open-and-shut case. Two suspects, U.S. soldiers from the near Spangdahlem Air Base, were quickly arrested and one of them, then 27-year-old Grant H., confessed to the crime. His statement is documented in the investigative records provided to LTO.

During his interrogation on August 19, 2023, he stated that he has been stationed in Germany for two years but wanted to resign due to a severe depression that had caused him to attempt suicide in the past. He had been on a new medication for two days and drank heavily on the evening of August 18. On his way home he and his friend got into a fight with a “stranger”. Fearing for his friend, he stabbed the stranger at least twice in the right side of his body and then they fled. When asked why he didn’t just try to pull his friend away, he replied: “I just freaked out.” The autopsy showed that Ovsjannikov died at the scene from internal bleeding.

Whose jurisdiction is it?

During the interrogation, not only is German detective chief superintendent B. from the Trier police present, but also U.S. special agent Angelo M. and U.S. special investigator Denise W., who also serves as interpreter for Grant. H.

The reason for this initial double investigation is a remarkable legal situation created by the NATO Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA). The SOFA determines which nation has jurisdiction over NATO soldiers who commit crimes in receiving states. This means that even though the manslaughter happed on German soil, it could fall under the jurisdiction of the U.S. military, specifically the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI). In accordance with SOFA, the Trier police department decided to hand the case over to U.S. authorities. We will come back to the question of whether German police had any discretion in its decision or whether it was inevitable.

In any way, the German investigation was closed, and their records were given to the U.S. military. Grant H. was transferred to U.S. custody and charged under Article 118 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) for unpremeditated murder.

In episode 189 from “Mordlust”, LTO editor-in-chief Felix W. Zimmermann and podcast host Paulina Krasa discuss the Wittlich case.

The trial began in September 2023 at a U.S. military court at Spangdahlem Air Base. Grant H. faced a general court-martial, the most severe type of trial a U.S. soldier can face in the military for violations of the UCMJ. A conviction at a general court-martial would be equivalent to a felony conviction in a federal district court. The court consists solely of U.S. military personnel. Even its jury comprised eight soldiers from the defendant’s air base Spangdahlem. However, Grant H. hired a civil defense attorney: Grover H. Baxley, expert for military criminal law from Virginia. According to Trierer Volksfreund, Baxley destroyed the prosecutor’s case during the trial and accused the friend of Grant H. of attacking Ovsjannikov. Though the central piece of evidence against Grant H. was not presented to the jury at all: his confession.

Why the jury never heard about H.’s confession

On June 15, 2024, after a motion hearing, the military judge ordered that H’s confession cannot be introduced as evidence. In a motion hearing a judge decides on certain issues before the trial begins, the most common pretrial motions are a motion to dismiss and a motion to suppress evidence. Without the statement in which H. describes freaking out and stabbing Ovsjannikov, the facts of the case remained unclear. Even independent observers were unsure whether H. or his friend were responsible for the stabbing. So, on October 11, 2024, H. was found not guilty by the jury. The decision led to a public outcry and demonstrations at Spangdahlem Air Base.

But why was the confession not admissible? When asked by LTO, the air base merely stated that the court-martial had come to the conclusion that the defendant’s statement was not voluntary and therefore could not be admitted as evidence. It remains unclear why the statement was involuntary, the air base repeatedly refused to release the reasoning for the order – open justice does not seem to apply to the U.S. military.

But the defense lawyer Baxley of all people explained to LTO why the judge allegedly did not admit his client’s confession. According to him, both the German and the American investigators made mistakes during the interrogation.

Grant H. allegedly confessed under the threat to spend the night in prison otherwise. In addition, the Koblenz public prosecutor general’s office, that was informed by a legal advisor of the U.S. military about the denied admission of the confession, confirmed to LTO, that Grant H. may have been threatened to be remanded in custody if he did not confess. But above all, H. allegedly was not properly instructed before the interrogation. Most notably, he didn’t know that Michael Ovsjannikov died according to Baxley. Baxley’s account of the judge’s reasoning is in line with the information of the Rhineland-Palatinate ministry of justice. According to the ministry, the U.S. military legal adviser also informed the Koblenz public prosecutor general’s office that the judge missed sufficient evidence that the manslaughter charge had been correctly translated.

“Threat” of investigative custody

Is it true that the investigators made “tactical errors” during the interrogation?

Concerning the alleged threat of investigative custody: according to the Koblenz public prosecutor general’s office, the two officers present at the interrogation rejected the accusation. But even if the officers pointed out the possibility of detention, this would not amount to an unlawful threat. Section 112 of the German Code of Criminal Procedure (StPO) allows for detention if a judge finds a strong suspicion that the accused person committed the offence and a risk of flight. A flight risk is often assumed in cases of homicide offences, therefore, explaining the possibility of detention if the suspect cannot dispel the suspicion does not seem unusual at all.

Enquiries to Baxley and the air base why the judge considered this to be an unlawful threat, nonetheless, remained unanswered.

German officers did not translate “suspicion of homicide”

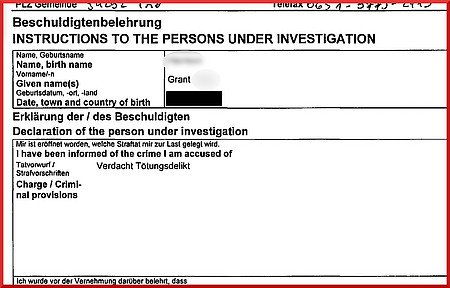

In any case, according to Baxley’s earlier statement, the key point in the motion hearing was the allegedly incorrect instruction of his client. LTO saw the instruction form signed by Grant H. dated August 19, 2023. It shows both that H. was instructed in German and how the passages were translated into English. Each individual phrase was diligently translated into English with one exception.

Right at the beginning of the form German police made a serious mistake.

While the sentence “I have been informed of the crime I am accused of” was correctly translated from German into English, the following words “Verdacht Tötungsdelikt” (“suspicion of homicide”) were not. Instead, there is only the placeholder “Vorwurf / Strafvorschriften” (“accusation / criminal provision”). If the suspicion of homicide had been translated in the form, the judge would most likely have considered the confession admissible, and Grant H. would probably have been convicted.

While the sentence “I have been informed of the crime I am accused of” was correctly translated from German into English, the following words “Verdacht Tötungsdelikt” (“suspicion of homicide”) were not. Instead, there is only the placeholder “Vorwurf / Strafvorschriften” (“accusation / criminal provision”). If the suspicion of homicide had been translated in the form, the judge would most likely have considered the confession admissible, and Grant H. would probably have been convicted.

The spokesperson for the Trier public prosecutor’s office confirmed that the phrase was only in German but said that the reason for this is unclear.

Right to a fair trial in the U.S. military

But is it on the other hand reasonable to suppress the confession because of this mistake? Baxley explained to LTO that the rights of members of the U.S. military are in many ways more extensive than those of American civilians. For example, Article 31 UCMJ requires a military suspect to be informed of the nature of the accusation. One mistake can have substantial consequences. Under U.S. criminal procedure law not only is illegally obtained evidence inadmissible, but also any evidence derived from it (“fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine).

But is it sufficient to imply from the missing translation, that H. was not informed properly about the accusation? In fact, the transcript shows that he confirmed being informed before the interrogation.

It reads: “Furthermore, the accusation was explained to me. So, I know why I’m being questioned today. Specifically, it concerns an incident that occurred last night in Wittlich, in which a person died violently. The police are investigating on suspicion of homicide. I was also informed that, based on the police’s previous investigations, I am currently suspected of having something to do with the homicide. Therefore, I was also informed here as an accused.”

German officers write German protocols

Doesn’t this passage prove that Grant H. was informed before the questioning? Not according to H.‘s lawyer Baxley.

The protocol is fully in German. Neither the original questions in English nor the original answers are documented. While the German officers did use a voice recorder for the interrogation, they repeatedly switched it on and off. H.’s voice as well as the word “homicide” or a similar term cannot be heard on the recordings. Again, there is no evidence that Grant H. was aware of the accusations against him.

The Trier public prosecutor’s office and Trier police confirmed to LTO that the dictaphone was only used sporadically. It only recorded “what was later transcribed for the protocol.” Accordingly, only the officers’ questions in German and the interpreter’s German translation of H.’s answers were recorded on tape, the original English answers were left out.

The Trier public prosecutor’s office adds that such fragmented use of the recorder is common for police interrogations. The dictaphone is not intended to record and document the spoken word, but is merely a tool for transcribing, replacing the need for a typist.

In retrospect, this practice – focused only on the German protocol – proved to be fatal. Had the interrogation been fully documented from the beginning, there would have been no uncertainty over Grant H.’s procedural rights.

Video proves knowledge of accusations

Even the German Code of Criminal Procedure (StPO) supports video and audio recordings of examinations of the accused. It states in Section 136, Paragraph 4 StPO that a recording of the examination of the accused may be made, except in cases where proceedings relate to intentional homicide. In that case, an audiovisual recording “is to be made” unless there are compelling reasons to the contrary. The Trier police did that but only after the first confession of H.

But the protocol of the audiovisual examination indicates that at the point of the recording, H. was already informed of the accusations. The protocol states in German that the interrogating officer explained to H.: “Then, as I said, I will now repeat the advisement for the suspect in German. The allegation here is the suspicion of homicide.” H. answers “Yes”, according to the protocol. But again, original questions and answers in English are not documented. On inquiry by LTO, the Trier public prosecutor’s office reviewed the interrogation video and provided the original wording: “So he will repeat the advisement as subject. And the allegation is, allegation of homicide.” H. replies: “Yes.” He continues: “Last night, at the event, a person passed away during the incident, and we are going to ask some questions about this.” Answer: “Yes.”

While this seems to confirm that Grant H. was informed of the accusations in English, his lawyer Baxley deems the video irrelevant. According to him, the crucial point is that his client wasn’t properly informed before his first round of questioning, therefore his statements were unlawfully obtained.

This seems at least questionable. The questions and answers in the video interrogation prove that the instruction regarding the accusations was merely repeated. The interpreter explicitly used the word “repeat.” H.’s confirmation with “Yes” should prove that the instruction was already given during the first interrogation, likely at the very beginning – as required by Article 31 UCMJ. Therefore, it is unclear why H.’s confession wasn’t admitted to the trial and with the order shut away in Spangdahlem it will remain that way.

Mistakes on both sides

After the video interrogation was completed, it was the turn of U.S. investigators. They also questioned H., to be sure, even under U.S. military law. But the U.S. investigators continued to make the same mistakes: special agent Angelo M. did not instruct H. on manslaughter, but only on aggravated assault. This was confirmed by Baxley and the Koblenz public prosecutor’s office. “Aggravated assault” is a crime that, according to Baxley, carries a maximum sentence of five years in prison under the UCMJ, while manslaughter carries a life sentence.

How can experienced investigators make such a rookie mistake? Aren’t special investigators supposed to know the procedural rules for questioning members of the military?

And the failure continues: At the motion hearing, interpreter and special investigator Denise W. was not summoned as a witness. Who, if not she, could have better testified about whether Grant H. was accurately informed of the charges in English at the very beginning of the questioning? Furthermore, the prosecutor could have appealed the order not to admit the confession to trial. But that, too, was not done. Why?

According to the air base, this was a “strategic decision” considering the potential effects on the evidence still available for the trial. Apparently, the prosecutor feared the potential delay due to the appeal which would have made the questioning of other witnesses on the stand more difficult.

What remains: A U.S. military court that won’t release its decision on the use of evidence. U.S. investigators who – despite knowing the strict rules – apparently misinformed the suspect, failed to call a key witness, and chose not to appeal an order that was clearly decisive for the case. And finally, failure on the German side: police officers that issued a form for instructions without correctly translating the charges. Plus, the decision not to record the first interrogation in full – even though Section 136 Paragraph 4 StPO explicitly allows for this, and possibly requires it. The Trier police and public prosecutor’s office thus bear part of the responsibility for the acquittal of Grant H.

Mistakes without consequences – at least under German law

One reason for the carelessness of German investigators could be that such mistakes are often without consequences under German procedural law. There is no “fruit of the poisonous tree”, instead courts weigh the competing interests on a case-by-case basis. Since the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) often prioritizes determining the truth, errors during instruction of a suspect rarely lead to the inadmissibility of statements. Some exceptions to this are codified in Section 136a Paragraph 3 StPO, like deception or the threat of torture.

Grant H.’s motion to suppress the confession would most likely not have been successful in a German court, not only because of less strict standards for admissible evidence, but also because the record shows that H. was informed of the accusations. And although the finding after gathering all the evidence cannot be anticipated, a German court would probably have convicted Grant H.

Who has the final say now?

So, we come back to the question, whether the German public prosecutor’s office was obliged to hand the case over to the U.S. investigators. The rules of the NATO Status of Forces Agreement mentioned before create a complex jurisdictional ping-pong:

Generally, in a case of manslaughter involving a German victim, Germany has the primary right to exercise jurisdiction (Article 7 (3) SOFA), but it can waive that right. Germany has generally waived its primary right to prosecute foreign NATO soldiers through Article 19 of the SOFA Supplementary Agreement unless the prosecution by the sending state may lead to the imposition of the death penalty.

But the German authorities can recall the waiver in a specific case if they hold the view that interests of German administration of justice make the exercise of German jurisdiction imperative (Article 19 (3) SOFA Supplementary Agreement). The provision names offences causing the death of a human being that is not a member of a force as one case making the exercise of German jurisdiction imperative. The manslaughter of a German citizen by a U.S. soldier should therefore be a prime example for recalling the waiver of German jurisdiction.

State administrative provision makes German investigations impossible

But in the end, the jurisdiction lands on the side of the U.S. According to an administrative provision of Rhineland-Palatinate (JBl. 2004, 92), there is an “agreement” with the U.S. authorities that even in cases of serious offenses, recalling the waiver is not justified if “after a careful consideration of the factual and legal situation, there is a reasonable prospect, according to human and legal judgment, that the case will be brought to a conclusion within a short period of time in the U.S. military criminal proceedings that is also appropriate according to German sense of justice.”

In a nutshell: Even if a U.S. soldier kills a German citizen on German soil, the jurisdiction generally remains in the hands of the U.S.– unless there is concrete evidence that the U.S. military justice system will not handle the case in a timely and appropriate way.

But how can one know in advance whether the U.S. military justice system will actually conduct the investigation quickly and in accordance with the rule of law? What tangible evidence could there possibly be to the contrary? This provision – besides completely disregarding the severity of the crime – requires German investigators to just guess. Furthermore, the public prosecutor’s office cannot decide this on its own but must obtain the approval of the state’s ministry of justice, which would turn the investigations into a political issue.

According to Spangdahlem Air Base, the waiver of jurisdiction has been recalled not once in the last 30 years. An inquiry of other German public prosecutors’ offices shows that the “transfer” of proceedings is almost always the rule, this concerns mostly traffic offenses.

In the Wittlich case, the Trier public prosecutor’s office also declared that it would not recall the waiver. The reason given to LTO was that “at the time, there was no doubt” that “U.S. criminal proceedings, just like German criminal proceedings, are conducted according to the rule of law.” In retrospect, the phrase “according to the assessment at the time” reads almost like an admission of error. The failure to recall the waiver later proved to be a mistake.

Moving on after Wittlich

The Wittlich case sparked a debate about NATO rules. The recently deceased minister of justice of Rhineland-Palatinate, Herbert Mertin, defended the concept before the state parliament and expressed skepticism about whether the German authorities should take on such cases in the future. Mertin stated in a state parliament’s session in December 2024, that public prosecutors in Rhineland-Palatinate cannot take over every case, otherwise the state would be straight-up circumventing the NATO treaty – with potentially significant diplomatic implications.

The state ministry of justice told LTO that the rules of the Status of Forces Agreement fall under federal jurisdiction. From Rhineland-Palatinate’s perspective, the decades-long practice has proven successful. The state’s public prosecutors have been working closely with the authorities of the U.S. armed forces for many decades.

Nevertheless, the ministry is now examining possible need for change. It plans to evaluate the experiences of the state’s public prosecutors and examine whether more specific guidelines for implementing the NATO SOFA are needed.

The German constitution could be one source for such a need for change, particularly change of the administrative provision that makes it a rule to hand over the case to the U.S. military authorities even in cases of serious crimes. In 2014, the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) recognized the right to a criminal investigation. It would clearly contradict Germany’s fundamental principles of the rule of law to give up jurisdiction, even in cases of serious crimes, to a foreign institution that is not bound by German fundamental rights.

Homicides committed by U.S. soldiers in Germany are rare. In 2011, a U.S. soldier from Spangdahlem was convicted of killing his child – by a U.S. court-martial. He was sentenced to 22 years in prison. However, as is widely ciriticized, U.S. military tends to show great leniency towards their own soldiers. One prominent example from Europe: In 1998, 29 gondola passengers were killed in a Cavalese cable car accident in the Dolomites. The cause of the crash was a U.S. military jet pilot cutting through the cables. He was flying much lower than allowed and twice the speed permitted. Due to the NATO Status of Forces Agreement, the pilot was tried before a U.S. court-martial and later acquitted.

• You can also read Felix W. Zimmermann’s commentary on this topic entitled “Criminal prosecution should no longer be outsourced“.

• You can also read Felix W. Zimmermann’s commentary on this topic entitled “Criminal prosecution should no longer be outsourced“.

This text is a translated and slightly revised version of the article published in German on March 5, 2025.

Zitiervorschlag

U.S. soldier acquitted by military court despite confession:

. In: Legal Tribune Online,

21.03.2025

, https://www.lto.de/persistent/a_id/56833 (abgerufen am:

21.03.2025

)

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.