The Wikileaks founder says he fears his own imprisonment, US government surveillance, and restrictions on the group’s funding have effectively scared off potential whistleblowers.

The Wikileaks founder says he fears his own imprisonment and US government surveillance and restrictions on the group’s funding has effectively scared off potential whistleblowers.

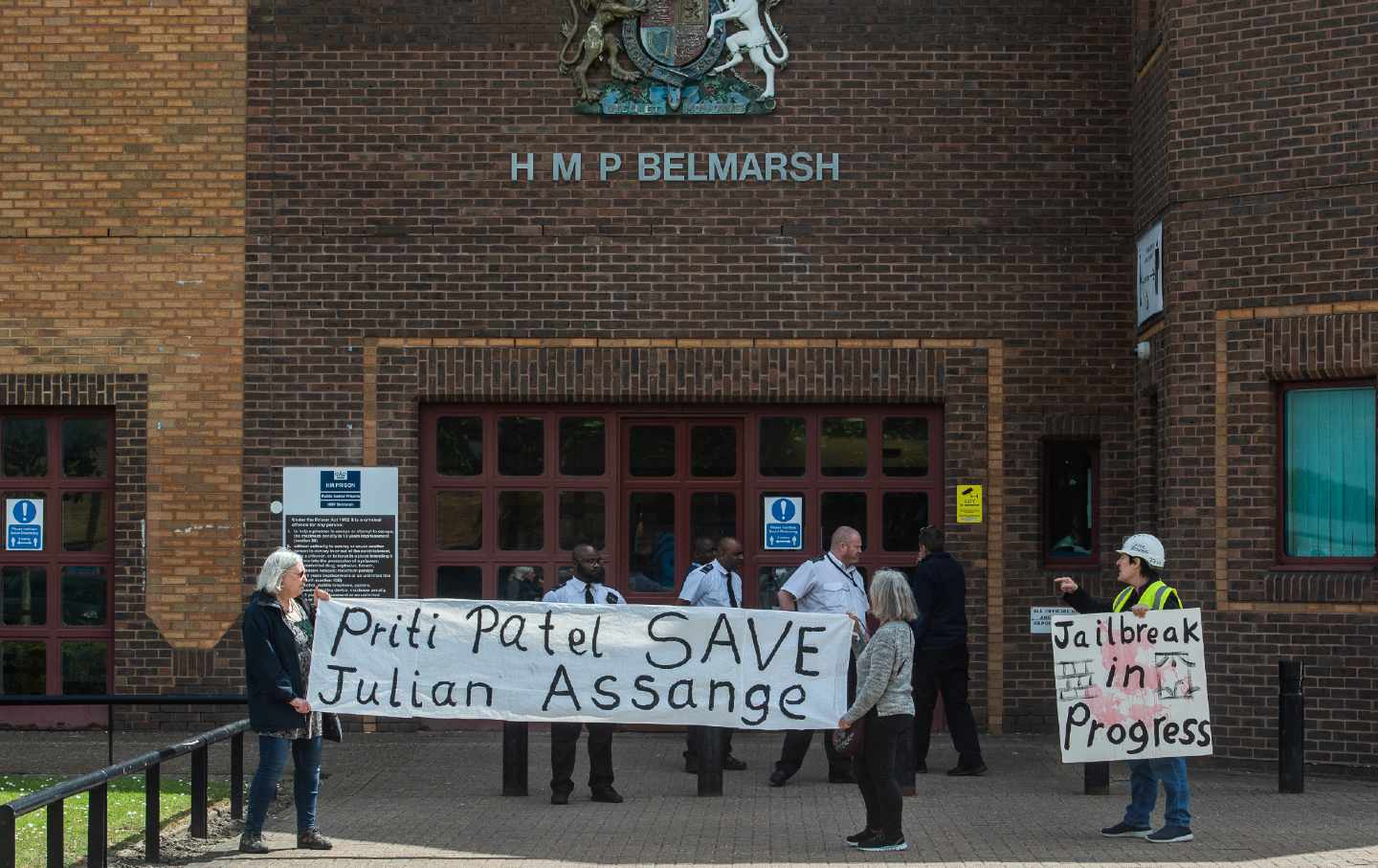

HMP Belmarsh—It is 2:30 pm on Wednesday, December 13, when Julian Assange strides into the visitors’ area. He stands out in the column of 23 prisoners for his height—6′ 2″—and flowing white locks with trimmed beard. He squints, looking for a familiar face among the wives, sisters, sons, and fathers of the other inmates. I am waiting, as assigned, at D-3, one of about 40 sets of small coffee tables surrounded by three upholstered chairs—two blue, one red—screwed into the floor of what looks like a basketball court. We spot each other, walk forward, and embrace. It is the first time I have seen him in six years. I blurt, “You’re pale.” Through a mischievous smile I remember from past meetings, he jokes, “They call it prison pale.”

He has not been outdoors—apart from a minute when police dragged him into a paddy wagon—since he took refuge in London’s cramped Ecuadorian Embassy in June 2012. The embassy’s French windows had afforded glimpses of sky. Here at Belmarsh maximum security prison in southeast London, his abode since April 11, 2019, he has not seen the sun. Warders confine him to a cell for 23 out of every 24 hours. His single hour of recreation takes place within four walls, under supervision. His paleness is best described as deathly.

I had arrived by train and bus an hour and a half earlier for registration and security inspection. The process began in the single-story Visitors Center to the left of the prison, as bleak a 1950s-style lunchroom as any depicted by Edward Hopper: cheap tables, chipped chairs, dim lighting, and banks of glass-fronted storage lockers. A kindly woman no younger than my 72 years told me I was early and suggested I have coffee. I ordered it from man in a crude kitchen, who poured boiling water into a mug of instant powder. Twenty minutes later, at 1:15, the door to an adjoining office opened for visitors to queue for passes. When my turn came, I gave my name to one of three uniformed women behind an elevated counter. She examined her computer and asked, “Are you here for Mr. Assange?” She was polite, almost friendly, as she recorded prints of my index fingers and told me to look at an overhead camera that took my photograph.

I presented three hardback books for Assange: my own Soldiers Don’t Go Mad; Sebastian Faulks’s new novel, Seventh Son; and Pegasus: The Story of the World’s Most Dangerous Spyware, by Laurent Richard and Sandrine Rigaud. She instructed me to hand them to the stout woman seated to her right. This woman examined my book, the history of a mental hospital for shell-shocked officers in the First World War. Looking at the title page, which I had signed for Assange, she forbade me to give it to him. I asked the question that must not be asked in a prison: Why? Nothing may be written in any book for inmates. I said it was my signature on a book I wrote, not a secret code. No matter. That was the rule. She ordered me to wait in the lunchroom while she checked on the possibility of admitting the other two books.

I drank the tepid Nescafeé and read the newspapers. More people, mostly women, arrived and joined the queue. A few of the women had small children or babies. One was with her son, a smiling lad who appeared to be about 12. Another woman reminded me of British movie moll Diana Dors, whose voluptuous form and cherry red lipstick would make an inmate yearn for the pleasures of home. An older South Asian woman limped by on a walking stick. One young woman’s hair was covered by a hijab. There were a few old men, possibly visiting their sons. It seemed most of them had been here before.

Back at the registration counter, the stout woman told me that Assange could not receive any books. Why not? He had to remove books from his cell before adding new ones. Again, I ask: Why? With a straight face, she answered, “Fire hazard.” Recalling Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, I think, but dare not say, “Manuscripts don’t burn.”

I deposited the books and everything else I had in a locker—telephone, pen, notebook, newspapers. I kept the permitted limit of £25 in cash to buy snacks inside. The women gave me a paper pass and a tag to wear around my neck: “H[is]. M[ajesty’s]. Prison Belmarsh—Social Visitor 2199.” I walked with the group across the grounds to the visitors’ entrance into the prison itself. There followed a series of checks and searches that involved verification of fingerprints, X-rays and a handsome golden retriever sniffing for drugs. At last, we entered the hall to await the prisoners.

Julian and I sit down, face to face, me on the red chair, he on one of the blues. Above us, glass globes hide cameras that record the interactions between inmates and their guests. Not sure how to begin the conversation, I ask whether he wants anything from the snack bar. He requests two hot chocolates, a cheese-and-pickle sandwich, and a Snickers bar. I invite him to come with me and make his own choices. Not permitted, he says. I go alone to line up at the booth run by volunteers from the Bexley and Dartford Samaritans. When my turn comes, I place the order. Out of sandwiches, the man says. The rest of the food is junk: potato chips, chocolate bars, colas, sweet muffins. I return to Julian, who has changed seats. The red chair is for prisoners, the blue for visitors, and a guard had ordered him to take the correct place. I put the tray with his hot chocolates, the Snickers, and some muffins and my instant coffee on the table. I ask why only unhealthy food was available. He smiles and says I should see what they eat inside on a budget of £2 per inmate per day. Per day? Porridge for breakfast, thin soup for lunch, and not much else for dinner.

Julian had thought prison meant communal meals at long tables, as in the movies. Belmarsh’s warders shove the food into the cells for prisoners to eat alone. It is hard to make friends that way. He has been there longer than any other prisoner apart from an old man who had served seven years to his four and a half. There are occasional suicides, he tells me, including one the night before.

I apologize for not giving him any books, explaining that they told me he had exceeded his limit. He smiles again. In his first months, they allowed him to keep barely a dozen. Later, they expanded it to 15. He pushed for more. How many did he have now? “Two hundred and thirty-two.” It is my turn to smile.

I ask whether he still has the radio he had struggled to obtain in his first year. He did, but it was not working due to a defective plug. Regulations permit each prisoner to have a radio purchased from prison stores. The authorities, however, said no radios were available for him. When I heard about it, I sent him a radio. It was returned. I then sent him a book on how to make a radio. That too was returned. Months passed, and I contacted one of Britain’s better-known former Hezbollah hostages to ask for his help. Listening to the BBC World Service on a radio his captors had given him preserved his sanity. At my urging, I tell Julian, he wrote to the prison governor. A media story that Belmarsh was denying Assange a privilege that Hezbollah granted hostages would be bad publicity. The prison gave Julian his radio. Does he want my help to persuade them to fix or replace the broken plug? No, it would just make unnecessary trouble for him.

How did he, a news addict, keep in touch? The prison allows him to read printouts of news stories, and friends write to him. With the invasions of Ukraine and Gaza, I say, now is an important time for whistleblowers to send documents to WikiLeaks. He regrets that WikiLeaks is no longer able to expose war crimes and corruption as in the past. His imprisonment and US government surveillance and restrictions on WikiLeaks’ funding wards off potential whistleblowers. He fears that other media outlets are not filling the vacuum.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Belmarsh does not offer him education programs or communal activity, like orchestra practice, sports, or publishing a prison journal, that are standard at many other prisons. The regime is punitive; although Belmarsh’s 700-odd inhabitants are on remand, awaiting trial or appeal. They are Category A prisoners, those who “pose the most threat to the public, the police or national security” and stand accused of terrorism, murder, or sexual violence.

We talk about Christmas, which is just another day in Belmarsh: no turkey, no carols, no presents. The prison is closed to visitors on Christmas Day and the day after, and the prison has informed his wife, Stella Moris, that she and their two young sons, Gabriel and Max, may not see him on Christmas Eve. He can attend Catholic Mass celebrated by the Polish chaplain, who has become a friend.

Visiting hour is ending. We stand and embrace. I look at him, unable to say good-bye. We embrace again, speechless.

The visitors walk towards the exit, while the prisoners remain seated. I am free to go outside, but he must return to his cell. Apart from occasional visiting days, his days are all the same: the confined space, the loneliness, the books, the memories, the hope that his lawyers’ appeal against extradition and life imprisonment in the United States will succeed.

As I pass through the automatic doors to the outside world, the last words of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, as translated by my late friend and literary agent, Gillon Aitken, come to me: “There were three thousand six hundred and fifty-three days in his sentence, from reveille to lights out. The three extra days were because of the leap years.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.