Note: Iowa, Virginia, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons did not provide data on life-sentenced individuals over the age of 55.

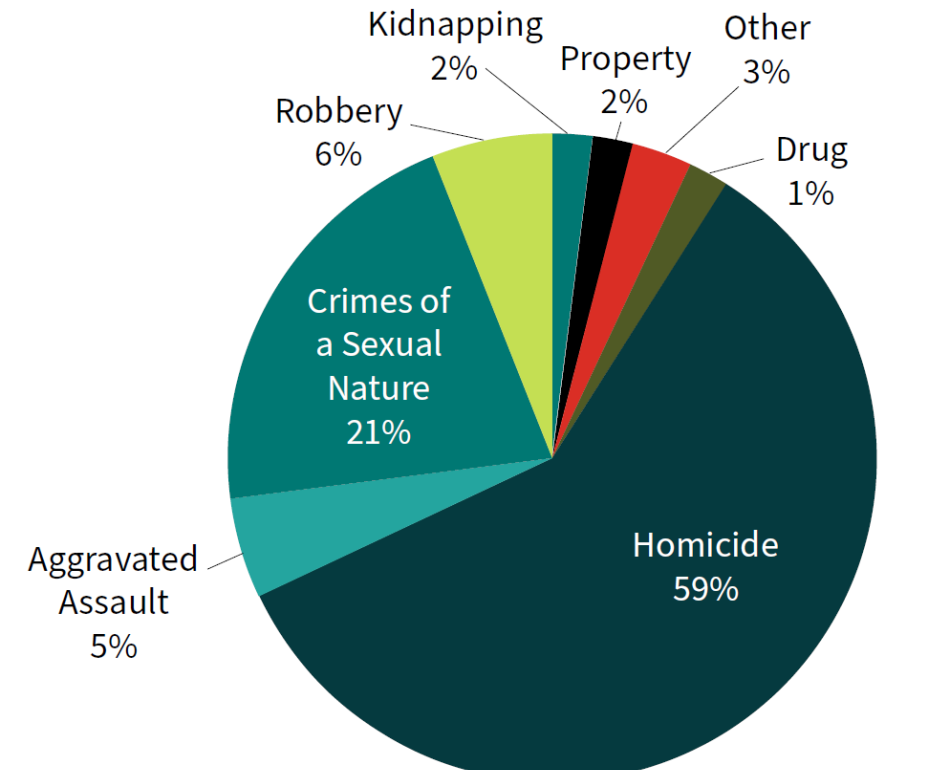

Crime of Conviction

Homicide and Other Crimes of Violence

Most individuals serving life sentences have been convicted of a violent crime. Homicide convictions—primarily for first-degree murder—accounted for 59% of the life-sentenced population in 2024. In most states, LWOP is the mandatory sentence for first-degree murder convictions, and in states with capital punishment, LWOP is typically required if a death sentence is not imposed.

In states such as Pennsylvania and Michigan, substantial proportions of people serving life sentences for murder were convicted of “felony murder.” This category of offense applies in cases in which someone was killed during the commission of a felony; this charge can apply to people who neither intended to kill nor anticipated a death, and can even apply to persons who did not participate in the killing.

In 2024, 25,395 people—a total of 14% of people serving life—had been convicted of aggravated assault, robbery, or kidnapping (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Distribution of Crime of Conviction Among People Serving Life Sentences, 2024

Note: This figure excludes data from Virginia and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. These jurisdictions did not provide full crime of conviction data on life-sentenced populations. Category totals do not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Crimes of a Sexual Nature

One in five people serving life sentences in 2024 had been convicted of a crime of a sexual nature (CSN). Recidivism rates for CSN have declined by 45% since the 1970s, and sexual assault victimization has decreased by roughly 65% across the last three decades. Still, since the 1990s, responses to CSN have become increasingly punitive, with individuals receiving longer sentences and, on average, serving a greater percentage of their sentences relative to persons incarcerated for other violent crimes, even murder.

Nonviolent Offenses

Individuals serving life sentences as a result of being convicted of nonviolent crimes comprise 3% of all people serving life sentences in 2024, or 6,199 people. There are 1,945 people serving life sentences for drug-related offenses. Of the 49 states that provided offense data, 11 reported not imprisoning anyone with a life sentence for this offense. Within the federal system, 939 people are serving a life sentence for a drug-related crime. Over 4,000 individuals are serving a life sentence for property crimes—another nonviolent offense. Eleven states reported not imprisoning anyone with a life sentence for this offense—it is worth noting these are not the exact same states which report zero life-sentences for drug offenses.

The high incarceration rates in Louisiana and Mississippi can be partly attributed to their “habitual offender” laws. Under these laws, someone can be sentenced to life or a virtual life sentence upon a second or third conviction, regardless of how far in the past the previous crimes occurred. Habitual offender laws are a tool used by prosecutors to ensure a life sentence.

Investigative reporting by The Appeal of the laws in Louisiana and Mississippi found that close to 2,000 people were serving life and long-term sentences in these two states because of these sentencing “enhancements.”

Youth and Emerging Adulthood

In 2024, a total of 68,429 people—more than one-third of all life-sentenced individuals—were under the age of 25 when they committed their crime. This report provides the first-ever state-by-state totals of persons serving life sentences for crimes that occurred before age 25 (see Table 10). Given emerging neuroscience on brain development and culpability, The Sentencing Project highlights this population as more states reevaluate the appropriate age for holding individuals fully accountable for crimes. States must confront this data, particularly where young individuals—whose cognitive and emotional development are still ongoing—are disproportionately serving life sentences. This information is crucial for evidence-based policy reform aimed at balancing justice with evolving understandings of human development.

Judicial and legislative recognition of emerging adults, typically defined as individuals from 18 up to 25 years of age, has resulted in significant reforms in states addressing the treatment of emerging adults within the justice system. These reforms often center on recognizing the developmental differences between adults and youth, especially given the advancements in adolescent neuroscience. For instance, Washington, DC allows for resentencing opportunities for individuals who were under age 25 when they committed their offense. Judges in Washington, DC are required to consider factors such as young age, childhood abuse, and rehabilitation efforts. Similarly, Vermont and Illinois have implemented reforms that either extend juvenile court jurisdiction or prohibit life without parole (LWOP) sentences for those under 21. California allows accelerated parole review for life-sentenced individuals younger than 26 at the time of their crime.

An increasing number of judicial rulings support late adolescence, marked by impulsivity and risk-taking, as a critical developmental stage that warrants more moderate sentencing considerations. Courts in Massachusetts, Michigan, and Washington have recognized that 18-year-olds are still not fully developed and thereby ruled mandatory LWOP for these teens unconstitutional under their state constitutions.

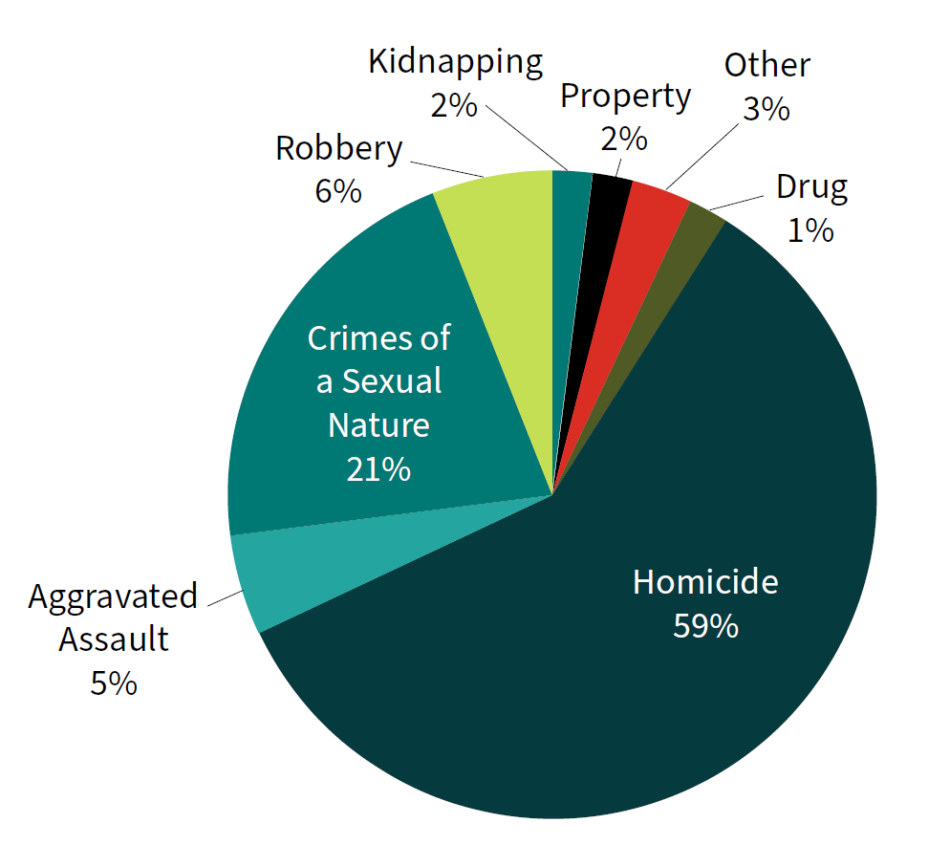

The data presented here cover individuals serving life with parole, life without parole, and virtual life sentences for crimes committed before their twenty-fifth birthday (see Figure 7). These figures help to describe the broader spectrum of individuals who could benefit from reforms that align with recent advances in adolescent and emerging adult neuroscience. As more research indicates the reality of reduced culpability and the considerable potential for change among young adults, there is growing pressure to extend legal protections and reconsider extreme sentencing for this population.

Figure 7. People Sentenced as Youth and Emerging Adults, by Type of Life Sentence, 2024

Note: This figure excludes data from Missouri and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. These jurisdictions did not provide data on the age at sentencing for life-sentenced individuals.

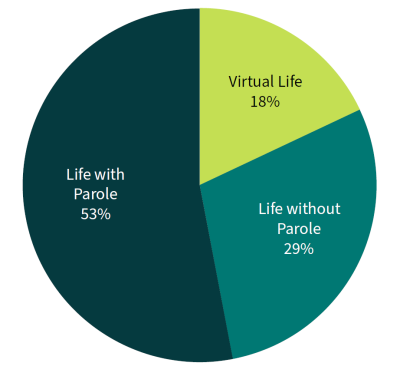

Race and Young Age

Black people disproportionately represent those serving life sentences, and this racial disparity is even more pronounced among youth and emerging adults (see Figure 8). While Black individuals comprise 37% of adults sentenced to life with the possibility of parole (LWP) in 2024, they account for 48% of those sentenced to LWP who were under 25 at the time of their crime. Similarly, Black Americans aged 25 and older make up 50% of those serving life without the possibility of parole (LWOP), but that figure rises to 62% for those who were younger than 25 at the time of their crime.

As The Sentencing Project has highlighted in its previous analyses, the intersection of being young and Black leads to disproportionately higher rates of life sentences, suggesting that age exacerbates racial disparities in sentencing.

Figure 8. Racial and Ethnic Composition of Those Sentenced to Life as Youth and Emerging Adults Compared to Individuals 25 and Older, 2024

Table 11 highlights states where the share of Black individuals is 70% or greater within the population of individuals whose offense occurred prior to their 25th birthday. Although The Sentencing Project’s data alone cannot definitively prove causality, there is strong evidence that racism significantly affects the experiences of Black individuals in the criminal legal system, from initial system contact, to sentencing, and beyond. Research shows that Black children as young as age 10 are often perceived as older than they are, which affects how they are treated compared to white or Latino youth. Black children are less likely to be given the benefit of the doubt and are seen as more culpable for similar actions than their white and Latino peers. Such biased perceptions contribute to disparities in arrests, convictions, and sentencing outcomes. By the age of 23, 30% of Black males in America have been arrested, compared to 22% of non-Black males. It is possible that these factors contribute to the racial disparities we observe among those sentenced to LWOP as well.

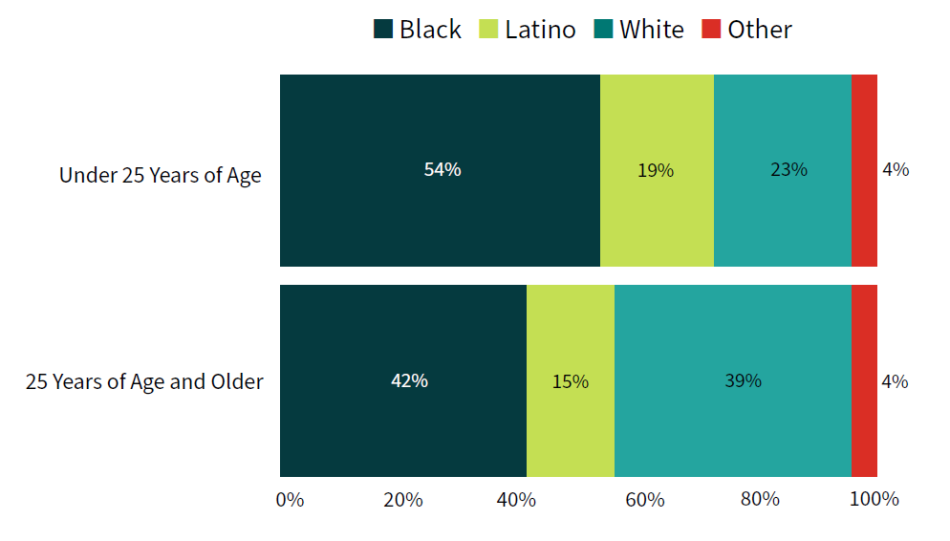

Crime of Conviction Among Youth and Emerging Adults

Like the broader population of life-sentenced individuals, most people sentenced to life for crimes committed before age 25 were convicted of violent offenses, particularly homicide. However, when categorizing convictions according to age group, homicide is disproportionately common among those under 25, and life sentences among adults reflect a wider range of crimes: 74% of life sentences for emerging adults and youth (under 25) were for homicide, yet for adults (age 25 and older), 49% of life sentences were for homicide, based on 2024 data.

Why Life Sentences Fail

Historically, sentences of life imprisonment were reserved for the most severe crimes, with actual time served often ranging from 10 to 12 years. The justice system employed a balance of incentives and penalties, encouraging rehabilitation through mechanisms like early release and good behavior credits. However, in the past 40 years, this approach has shifted dramatically. Lawmakers have expanded the use of life sentences, applying them to a wider range of offenses, and increased the mandatory time people must serve before becoming eligible for parole. Opportunities for early release based on good behavior have diminished, and wait times for parole review have lengthened substantially. Today, the focus of life imprisonment has shifted from a balanced model of punishment and rehabilitation to one primarily centered on punishment, with little consideration for reform or second chances.

Extensive research has demonstrated that life sentences fail to achieve the primary objectives of imprisonment, which include deterrence, incapacitation, retribution, and rehabilitation.

The purported broad deterrent value of lengthening prison sentences is not supported by the evidence. People do not engage in the rational cost-benefit analysis that deterrence theory requires before they engage in crime. Many violent crimes are impulsive, emotionally driven, and committed without awareness of the gravity of the legal consequences. Yet claims of the benefits of “teaching people a lesson,” popularized as “tough on crime”, have supported harmful policies like three strike laws, mandatory minimum sentences, and habitual offender laws.

Incapacitation as a goal of life sentences also fails. Most people age out of criminal conduct within a decade or so, and are usually “aged out” by their 30s. Imprisoning people for years or even decades beyond the point of dangerousness does not prevent crime.

The retributive principle of “an eye for an eye” often serves as the rationale for supporting life and long prison sentences, but upon closer examination, this logic falters. Francis Cullen, distinguished research professor emeritus at the University of Cincinnati’s School of Criminal Justice, argues that such punishments frequently become grossly disproportionate to the crimes committed given the wide variance in surrounding circumstances and culpability. These factors mean that the punishment rendered by life sentences far exceeds the balance intended by retributive justice. Additionally, these sentences are deeply affected by racial bias, further distorting any sense of fairness. Rather than ensuring justice, life sentences often impose far more punishment than is warranted by the offense, resulting in a system where the idea of proportionality is lost.

Rehabilitation has often been unfairly stigmatized, but when implemented effectively, it produces meaningful results. Unfortunately, many life-sentenced individuals and people serving long-term sentences are excluded from rehabilitative programs. Because persons with shorter sentences receive priority access to rehabilitation opportunities, life-sentenced individuals can be left out completely or subjected to extremely long program waitlists.

Despite these barriers, peer-driven initiatives have emerged organically within prisons across states such as California, Louisiana, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Lifer groups in these states have created supportive peer-to-peer rehabilitation communities that help imprisoned people work through their challenges, find friendship and acceptance, and contribute to personal transformation. Many released lifers credit these groups for their successful reintegration into society, underscoring the importance of community-driven recovery and rehabilitation efforts for those serving long sentences.

By expanding access to these programs, particularly for people with long-term imprisonment, prisons can better fulfill the promise of rehabilitation.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.