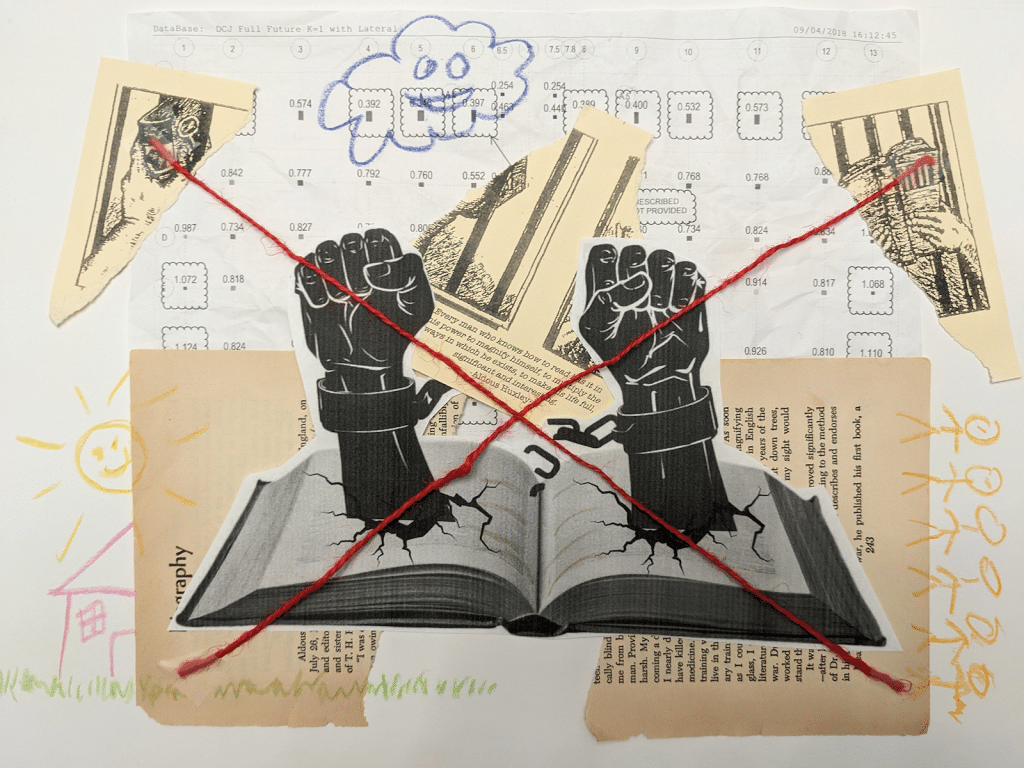

The Wisconsin Department of Corrections’ new ban on Wisconsin Books to Prisoners highlights the arbitrary rules governing incarcerated people’s access to books.

Wisconsin Books to Prisoners (WBTP), a Madison-based organization that sends free books to people incarcerated across the state, announced on September 17 that the Wisconsin Department of Corrections (DOC) has barred it from doing so—again. The announcement came just a few days into Prison Banned Books Week, a nationwide campaign highlighting the widespread and capricious practices of restricting access to literature in state prison systems.

WBTP first learned of the ban in August, after years of disputes with the DOC about sending in used books—which prison officials have forbidden on and off over the years, sometimes requiring the organization to send in new books only. The organization waited to go public in order to make a last-ditch effort to get the Wisconsin DOC to change course, and then coordinate a response, explains Camy Matthay, who co-founded WBTP in 2006.

Sarah Cooper, Administrator of the Wisconsin DOC’s Division of Adult Institutions, told WBTP in an August 16, 2024 email that state prison officials had instituted a number of new restrictions on incoming mail, citing the possibility that people could use books to smuggle illegal drugs into prisons. Cooper wrote that she wasn’t worried about WBTP itself sending drugs. Instead, she claimed that DOC wanted to prevent drugs coming in from fraudulent senders pretending to be WBTP: “So our concern is not with your organization, but with those who would impersonate your organization for nefarious means,” she wrote.

It’s not clear whether or not this has ever actually happened, or whether the Wisconsin DOC is even claiming that it has. In her email to WBTP, Cooper stated that drugs have made their way into prison via fraudulent mailings “under the guise of legitimate agencies, organizations and even legal entities,” including various government offices and attorneys. But it does not claim that DOC has ever received mail falsely purporting to be from WBTP. Wisconsin DOC spokesperson Beth Hardtke tells Tone Madison via email that “donated books have been among materials that have tested positive for drugs.” Hardtke did not clarify how many times this has happened, which drugs were found, whether those drugs were connected to recent overdose incidents in Wisconsin prisons, or whether any of those books purportedly came from WBTP.

DOC officials did not answer repeated questions from Tone Madison about whether the agency keeps statistics on contraband items seized in state prisons, what percentage of that contraband arrived in the mail, or what percentage of inmate mail is found to contain contraband.

Matthay estimates that WBTP has mailed more than 17,000 books during its 18 years in operations—all, she says, “without a single instance of contraband.” She says she understands the importance of preventing overdose deaths in Wisconsin prisons, and especially the rising concern about fentanyl. “It concerns us too, but we don’t feel that it’s justifiable to, really, prohibit thousands of people in prison from reading material because of some bad actors,” Matthay says.

Years of shifting rules

Wisconsin Books to Prisoners has navigated the DOC’s changing rules and barriers since it launched in 2006, as a project of downtown Madison’s Rainbow Bookstore. (Rainbow, a long-running and beloved outpost for radical politics, closed in 2016). WBTP set out to follow the DOC’s mail policies at the time, but it took less than two years to run into trouble. In May 2008, DOC hit the project with its first ban, ostensibly because Rainbow Books wasn’t an authorized vendor for the prison system and therefore couldn’t be trusted to keep out contraband. But as Wisconsin Public Radio’s Gilman Halsted reported at the time, a DOC spokesperson “couldn’t say whether any contraband had been found in books sent from Rainbow before the Department banned them.” By November of that year, DOC began allowing the project to send in books again, but only new books.

So began an intermittent push-pull between WBTP—often with help from the ACLU of Wisconsin—and the Wisconsin DOC over the terms of mailing in books. Could used books be allowed? What about books with cellophane? Or books with written receipts? Is Room of One’s Own an approved vendor? Is WBTP an approved vendor? Does the DOC have any evidence of contraband coming in via books? Do all of DOC’s prisons follow the same rules in the same way? None of these questions have ever been settled for good, though for years at a stretch, WBTP has operated with little trouble.

Matthay takes a diplomatic approach with the DOC, despite the frustrations of dealing with unclear, abruptly shifting policies. Over the years, she’s appealed to individual wardens and administrators, hoping that they can use their discretion to improve access to books for at least some prisons. She says she’s talked with prison librarians and even guards who sympathize with WBTP’s basic pitch—that robust access to books in prison reduces recidivism, aids in rehabilitation, and makes the prison environment less violent. “Even guards at Boscobel, the maximum-security prison, have said they have no objections to us sending books because [they’d] rather have prisoners reading than twiddling their thumbs,” Matthay says. “It creates safety for everyone.”

At different points, prison officials have allowed WBTP to send used books, as long as they were clean and in good condition. According to a timeline WBTP shared with Tone Madison of correspondence with Wisconsin DOC administrators, that was the case fairly consistently from February 2018 through the end of 2023. But in January 2024, Robert Miller, Security Chief of the department’s Division of Adult Institutions, told WBTP that only new books would be accepted going forward. Miller wrote that Wisconsin prisons “are experiencing a large amount of narcotics and foreign substances on paper.”

WBTP wrote back in May, asking the DOC to allow used books again. Matthay has also asked DOC if she can assuage concerns about impostor mail by providing prison officials with US Postal Service tracking numbers for each item WBTP sends. “I have yet to get a response,” she says.

Smuggling literature and public health

Fentanyl overdoses are a public health problem, whether they happen behind prison bars or not. But books are not the culprit—or at least, DOC officials have yet to offer convincing evidence that books serve as a prominent conduit for the drugs getting into prisons. Illicit drugs are brought into American prisons far more often by staff than via mail, something COVID gave us an accidental experiment to test. Many states—and federal prisons—have restricted mail in the last few years. Systems including the Wisconsin DOC have increasingly moved to mail-scanning systems that prevent people from holding the actual physical items they receive—drawings from their children, greeting cards, photos of loved ones. Instead, they get what are essentially photocopies. Advocates point out that overdoses have increased after mail bans in places like Missouri.

“DOCs are overwhelmingly targeting paper mail as the primary conduit for predominantly fentanyl,” Dr. Moira Marquis, founder of Prison Banned Books Week, says. “And this just simply is not borne out as warranted by the evidence that we have that’s available.” For instance, Florida’s Department of Corrections announced in late 2021 that it would move to digitizing most prisoner mail, arguing that this would help keep contraband out. But at the very same time, the Tampa Bay Times reported that mail accounted for only 1.7 percent of the contraband items Florida prison officials found between January 2019 and April 2021.

It is not possible to overdose on fentanyl by merely touching it, despite the years-long rash of panicked anecdotes about cops and prison guards needing Narcan after so much as breathing near some fentanyl or grazing it with a finger. But the urban legend, paired with a recent spate of claims that people are using drug-soaked paper to smuggle dangerous drugs into prison, makes it easier for prison officials to justify new mail restrictions. But many documented examples of drug-soaked paper are often smuggled in by staff. An ex-federal prison nurse was charged in a case last year in Miami and several staff have been charged in Chicago’s Cook County Jail.

It is true that people imprisoned at Wisconsin’s troubled Waupun Correctional Institutions have died from fentanyl overdose and other causes, including neglect. These deaths sparked the departure this March of DOC Secretary Kevin Carr and several arrests, including the arrest of the former Waupun warden. But we don’t see the Department of Corrections banning all wardens.

A possible explanation of this hasty rule change is staffing issues. Many jobs in Wisconsin prisons were unfilled in 2022, although funding increases seem to be turning that around. If mail intake positions are unfilled, it may be possible that this DOC policy change is papering over continued staffing issues, and destroying access to books as a side effect.

While the Department of Corrections claims this is all about safety, Wisconsin prisons provide poor health care and few real answers for substance use issues. It’s worth remembering that research shows two years of lost life expectancy for every year someone spends in US prisons.

What’s the recourse? What are the rules?

As of this writing, WBTP hasn’t sued the state, but is exploring its options for convincing a court to reverse the Wisconsin DOC’s new restrictions. Matthay sees the potential for a First Amendment approach: “We have rights of free speech, so to speak, as distributors,” she says.

Marquis suggests another Constitutional angle: “Denying some book distributors access to communication with incarcerated people and allowing others [based on] unpublished criteria, without any ability to apply for a selection process or to meet any kind of criteria, is a 14th Amendment violation because it’s arbitrarily discriminating,” Marquis says. “Why is Wisconsin Books to Prisoners any more at risk of inadvertently being a conduit to contraband than any other book distributor? They can’t explain that, and they won’t be able to in court.”

The ACLU of Wisconsin has worked with WBTP in the past, but isn’t yet commenting on the specific legal issues at play in this latest ban.

“People in prisons already have extremely limited access to educational materials, and it is incredibly harmful to further limit their basic right to information through indiscriminate, unfounded mail policies,” ACLU of Wisconsin spokesperson David Gwidt wrote in an emailed statement to Tone Madison. “The services provided by non-profit organizations to increase access to these materials are commendable and should be encouraged, not banned. We are currently investigating the issue.”

If it sounds daunting to challenge DOC’s mail restrictions, it’s just as hard to understand and follow them. A person looking to read up on these policies for the purpose of successfully obeying them will very likely come away confused. The DOC’s webpage on sending mail to inmates doesn’t say anything about books. DOC’s Inmate Handbook mentions books but provides no guidance about getting books in the mail.

The department encodes its formal policies in the state’s Administrative Code, and one chapter spells out rules for inmate mail and access to books. It states that “Inmates may only receive publications [including books] directly from the publisher or other recognized commercial sources in their packages.” This policy has been in place since before WBTP existed. On the face of it, it’s not clear whether WBTP or the bookstores it has partnered with count as “recognized commercial sources.” The code also says nothing about some of the main issues WBTP and DOC have argued about over the years, like whether used books are allowed. And of course, it says nothing about the finer points of the most recent restrictions DOC has enacted.

In fact, it’s not clear what these new restrictions are, on a basic level. They’re not changes to state statute (which would require an act of the Legislature) or to the Administrative Code (which is also a body of law, but works a bit differently—executive-branch agencies craft the rules in the code pursuant to state statute, with legislative oversight). Are they formally documented DOC policies, internal memos or updates to an internal employee handbook, or planned future updates to the Administrative Code? Are they individual administrators’ new interpretations or applications of existing documented rules? Can people actually read these rules anywhere, outside of the correspondence between DOC and WBTP?

Tone Madison asked the DOC if the new restrictions constituted a written policy, and if so, whether it was available somewhere for the public to read. DOC spokesperson Beth Hardtke responded by sharing a few different documents: a press release about a 2021 change to prison mail policies, a 2022 press release about new screening procedures for people entering DOC’s adult facilities, and a document detailing new policies DOC adopted in summer 2024 for handling legal mail (mail from attorneys, courts, government officials, etc.). None of these shed light on the broader mail restrictions DOC has recently adopted. Cooper told WBTP in her August email that banning the organization from sending books is “part of a full, broad and comprehensive strategy to reduce drugs and save lives,” but nowhere has DOC spelled out fully what that strategy is or what rules people must follow to stay on the right side of it.

Even people who deal with the prison system professionally find this confusing and exasperating. Oren Jakobson, a criminal-defense attorney with the Madison-based firm Community Law SC, says he’s also having trouble finding clear, written documentation of DOC’s new mail restrictions. He’s found that prison rules are often a moving target.

“That’s one of the frustrations that I’ve routinely run into interacting both with the DOC and with individual county jails in the state,” Jakobson says. “There are occasionally well-documented policies. Those are frequently not followed. There’s a lot of inconsistency with respect to getting any items in to an inmate within the DOC. There’s wild disparities across the different prisons individually, and it’s often difficult to navigate even finding what the policy is, especially in any kind of timely manner, and particularly for someone who’s not an attorney. But even for us, we spend an inordinate amount of time just navigating, like, what exactly are their rules? And says who? And then, will the people who are actually receiving things follow those rules? Or do they have a completely different set of rules that they’ve been trained on?”

The tangle of rules and discretionary enforcement decisions can also get in the way of legal paperwork. “I routinely get complaints from clients that there’s extended delays when we send paper discovery from our law firm to our clients, and routine complaints that their paper is taken away from them and confiscated, and I have to send in new copies at different times,” Jakobson says.

A long history of control and flawed rationales

It’s particularly important to note that Wisconsin DOC’s ban is “denying incarcerated people access to free reading materials,” says Marquis. Like people locked up in state prisons across the country, people incarcerated in Wisconsin DOC prisons can still get cheaply made tablets from a private vendor, then purchase ebooks and other media on those. This gives prison officials and vendors yet another way to control what books people can or can’t access, as Marquis explained in a September 17 piece for Slate. That’s if they can afford ebooks at all; the free ebooks available are only materials long out of copyright. Inmates who can work earn extremely low wages, which are often garnished to cover medical expenses and fines. They also rely on for-profit, price-gouging vendors for all manner of products and services, from food and household goods to video calls.

“If you can only order books from Amazon, or you can only order books from Barnes and Noble, that’s the market rate, and people inside are not earning money,” Marquis says. “It really is censorship by another name.”

Marquis advocates for incarcerated people’s access to reading materials and writing programs. She also studies the efforts prison systems around the U.S. make to obstruct those very things. Marquis co-edited Books Through Bars: Stories From The Prison Books Movement, and served as the lead author of PEN America’s 2023 report Reading Between The Bars: An In-Depth Look At Prison Censorship. With Prison Banned Books Week, which ran this year from September 15 through 21, Marquis is challenging people to consider prisons in the broader context of book-banning.

“We’re trying to raise awareness that prisons are the largest censors in the United States,” Marquis says, echoing the motto of the event. “There’s a lot of public conversation now about schools and libraries censoring certain kinds of books. This is raising awareness in the general public that there is censorship in the United States, which is something that maybe people had assumed hadn’t ever been the case. But actually, censorship has been going on in U.S. prisons forever, and the justification of denying incarcerated people intellectual freedom and free expression is actually the basis [for] the paternalism that we see in school and library censorship is predicated on.”

Prison systems across the country limit incarcerated people’s access to books with a few key mechanisms. One, prisons place all manner of restrictions on mail in general, which are only getting tighter as more prisons try to do away with paper mail entirely. Two, prison officials have broad latitude to ban all kinds of specific books, and often make absurd and arbitrary decisions about which titles prevent a “security threat” or are too “explicit.” Wisconsin’s DOC has banned hundreds of titles, which range from political texts (but not Mein Kampf, that one is allowed) to books on healthcare to instructional books about tai chi to Dungeons And Dragons rulebooks. Three, prison libraries and digital tablets often have limited selections, which only makes access to mailed-in books more crucial.

Prison book bans often start with criteria that, on the surface, might seem pretty reasonable to most people, Marquis explains. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1987 ruling in Turner v. Safley allows states to restrict prisoners’ First Amendment rights, provided those restrictions serve a legitimate security interest. This still leaves prison officials a great deal of discretion in interpreting and applying criteria, and gives prisoners little recourse.

“When it’s applied, it’s applied in this completely overblown, hysterical kind of way that takes in all kinds of books in a dragnet,” Marquis says. “[Books banned in prisons include] visual dictionaries that are designed for people who are totally illiterate to learn how to read, medical textbooks, classic literature, histories of racial injustice in the United States—all kinds of things that are just not, in any way, going to affect a prison’s collapse. And yet they’re justified as potentially doing that.”

Marquis says the most commonly banned book in U.S. prisons is 2015’s Prison Ramen. It’s literally a cookbook, in which formerly incarcerated author Gustavo “Goose” Alvarez collects recipes prisoners can make with the limited ingredients and equipment available to them. Coincidentally, Wisconsin Books to Prisoners published a cookbook of its own, Canteen Cuisine, in 2019. Prisoners kept asking WBTP for cookbooks, so the organization’s volunteers solicited recipes from people incarcerated all over Wisconsin.

The work continues

LGBT Books to Prisoners, which grew out of WBTP in 2007, still shares space and mutual support with WBTP but has a nationwide scope. Because LGBT Books to Prisoners sends books to all states, that group is already very familiar with the arbitrary bans and rules that prison systems create. So are staff members at east-side bookstore A Room of One’s Own, which supports both WBTP and LGBT Books to Prisoners by gathering monetary donations and maintaining online wishlists of books that incarcerated people have requested. Customers can order from those wishlists to help the store provide those books directly.

“Obviously many specific titles are banned in prisons, but there’s also these other logistical elements I don’t know if people are aware of,” says Room of One’s Own Receiving Manager Mira Braneck, who currently heads up the store’s books-to-prisoners efforts. “It has to be sent in very specific packaging, very plain packaging. Some prisons, you can only send X number of books at a time. We’ve had packages sent back on both counts. It’s the content, but also these restrictive measures so folks can’t get books, almost regardless of what the books are. And I think we’re seeing that right now with a very broad blanket refusal of allowing this group to continue their work and our work.”

In the meantime, Room plans to keep setting aside books and monetary donations so that WBTP can pick up where it left off.

“This is the work that I’m proudest of that I do at Room, because it is a population that is so deeply in need of books, and it is often near impossible to get them for folks in prison,” Braneck says. “What’s happening is emblematic of that. We will continue to do it. We aim to continue to do it. LGBT Books to Prisoners is continuing to send books nationally. So this work is not going away, even with this new directive. This is an interim, but we hope to be able to continue sending books to folks in Wisconsin.”

Matthay is hopeful that Wisconsin Books to Prisoners will eventually prevail in court. While its main work is in limbo, Matthay says members of the community can still support the organization by donating money or purchasing books through WBTP’s online wishlist at A Room of One’s Own. WBTP is also organizing an online letter-writing campaign via resources linked on its Linktree page.

She’s also always looking to fill gaps in WBTP’s library, based on requests the organization fields from incarcerated people. Those include “books on trades, like carpentry, plumbing, wiring, heating and cooling, how to get a [commercial drivers license],” Matthay says.

“Those are books that just don’t come in. We’re not getting enough books donated [about trades] to meet the needs and interests that are expressed,” she adds. Matthay notes that prisoners also need more books on learning Spanish, learning to draw, exercise, and how to start a business or non-profit. Plus, WBTP needs more copies of the Prisoners’ Self-Help Litigation Manual, by attorneys John Boston and Daniel E. Manville. It’s not cheap—it retails for $72 per copy through Oxford University Press, and the Wisconsin DOC has, again, often insisted that WBTP only send new books.

“I tell people, ‘You can assume the reading interests of prisoners are the same as you’d expect of the patronage of any public library,’” Matthay says. “It’s really all over the place, but prisoners—at least many of them that write to us—are clearly trying hard to prepare for re-entry as productive citizens, people that are responsible community members who can contribute to the community.”

In the meantime, the ban might give WBTP a chance to make progress on a long-in-the-works collaborative project: a book of book reviews written by prisoners. Matthay says the collection “ranges all across the spectrum, all different writing abilities too, but the appreciation for literature really shines through.”

Dorothea Salo, a distinguished teaching faculty member at UW-Madison’s Information School and an expert on digital privacy and security, sees the DOC’s latest crackdown on Wisconsin Books to Prisoners as irrational and excessive. “People in prisons want to read books, and people outside want to get them books to read—I just don’t see where the problem is,” Salo says.

“I have to think there was a better resolution to this available, but the DOC just decided not to talk about it or pursue it,” Salo adds. “Again, that’s just horribly cruel to imprisoned Wisconsinites.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.