On an August evening in 2021, the best-selling Chinese novelist Hao Qun, who writes under the name Murong Xuecun, was procrastinating in his one-bedroom apartment. He needed to be at Beijing Capital International Airport around 6 the next morning to catch a flight to London, but he found it hard to pack. Though Hao had a valid tourist visa to Britain, the Chinese government had kept tabs on him for years, and it was possible that he would be prevented from leaving; other public intellectuals had tried to travel abroad only to discover that they were under exit bans. Hao might have been packing for a life of exile or a futile trip to the airport.

Listen to This Article

His forthcoming book, “Deadly Quiet City,” would be published soon, and Hao’s editors were worried for his safety. A collection of nonfiction, it was about the terrifying, Kafkaesque early days of the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, where residents had been subjected to an unrelenting information-suppression campaign. The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market was considered the pandemic’s origin point, but the state had strangled reporting on daily life there. When Hao arrived at the shuttered market in April 2020, he was met by tired guards, who, to discourage him from taking photos, presented coercion as patriotic duty. “You know, the Americans are exhausting their ways to frame our country,” one of them said. “It’d be no good if your photos were used by foreign media. Please cooperate.”

Hao was not deterred. Square-faced and of average height, he has the look of a Chinese everyman. You can picture him striking up conversations with ease, and over the course of his reporting trip he talked to people from all walks of life — office employees, store owners, taxi drivers and migrant workers. Some introductions were made by reporters, who were forbidden to cover many aspects of the pandemic. These meetings were often hourslong affairs. “At the time, people had a strong desire to talk,” Hao recalls. One interview with a citizen journalist named Zhang Zhan lasted from noon until after dusk. All the while, he tried to shake off the eerie suspicion that he was being watched. It was a paranoid hunch, but it wasn’t an irrational one. After all, the guobao, or Chinese secret police, had shadowed him for the better part of a decade. In Wuhan, he conducted conversations at odd locations: on a street lined with office buildings abandoned during the pandemic, or by the windy bank of the Yangtze River.

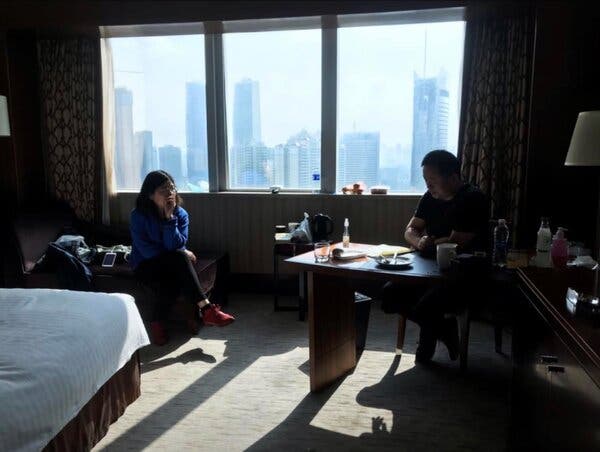

In his hotel room, he sometimes made phone calls under a blanket to ensure privacy. One night, the sound of two men speaking in hushed voices outside his door left him thinking of citizen journalists who had disappeared after posting reports from the city. A distant memory flashed: Five or six years ago in Beijing, Hao was invited to a celebration at the Swedish Embassy. A couple of guobao officers showed up at his home a day before the event. “You won’t be able to go,” one of them informed Hao, hinting that they would physically stop him if he tried. Feeling rebellious, Hao insisted that he would go, but the guobao taunted him. “Look at yourself,” one of them said. “How many blows would you be able to withstand?” The men in the hallway eventually left, but Hao was covered in cold sweat. Days after he departed from Wuhan, he got word that Zhang had been arrested.

“Deadly Quiet City,” which was published in the United States in March by the New Press, captures how such state-enforced silence, combined with inadequate access to medical care, intensified ordinary people’s despair during the crisis. Reading these stories, you not only feel for Hao’s subjects but also fear for the political trouble Hao’s unflinching clarity invites. After Hao submitted the manuscript to Hardie Grant Books, his Australian publisher, in spring 2021, his editors urged him to leave China out of concern for his safety. He equivocated. A few years in prison was a price he was willing to pay for the book’s publication.

His editors continued to press him, and by midsummer he had decided to flee. He boarded the flight to London successfully and, after a spell, moved on to Melbourne. When he spoke to me in late January, he seemed to be in a bit of disbelief at where his life ended up. Exile in Australia was worlds away from the circumstances in which he first rose to prominence. As China strove for a larger role on the international stage at the turn of the century, the arrival of the internet and a relatively relaxed political environment sparked an unprecedented boom in self-expression. Afforded new license, many writers of Hao’s generation tested the boundaries of Chinese literary culture, writing stories that portrayed the lives of the rapidly growing middle class and the opulent nouveau riche while revealing the ethical toll an increasingly materialistic worldview took on their nation. These writers experimented with subjects that were quotidian but taboo on the page — corruption, sexual desire and evolving gender roles — often wielding confession to upend convention.

There is a Chinese idiom: “Spilled water will not flow backward.” This period opened a floodgate of creation that forever altered contemporary Chinese literary culture. Where the government once vetted all writing for its conformity to state values, the internet provided a marketplace of ideas where writers could independently attract tremendous audiences. In today’s China, though, the pursuit of free expression requires writers to weather new political pressures and operate under the ever-watchful eye of a complex state surveillance system. This can resemble a high-stakes game of Whac-a-Mole in which writers, editors and online publishers try to outmaneuver the Chinese Communist Party’s apparatus, using any opportunity and resource at their disposal to chronicle life as they see it.

In 1978, as China emerged from Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution and decades of isolation, the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping inaugurated his Opening Up policy. This was both an overture to foreign business and a kind of domestic glasnost. Over the next few decades, “openness” became a political buzzword. By 2001, that ethos had borne its most symbolic fruits: After campaigning for more than a decade, China became a member of the World Trade Organization and was selected to host the 2008 Summer Olympic Games.

Jiang Zemin, Deng’s successor, applied the old man’s vision to cultural work, which, as he said at the 2002 national party congress, should be “geared toward modernization, the world and the future.” Soon the government introduced policies, like tax relief for companies that transitioned from state-owned bureaucracies to market-driven enterprises, that equipped creative industries to produce dynamic and competitive work.

This general openness coincided with the popularization of the internet, which was new enough that it largely eluded outmoded print-era censorship. For much of the first decade of the new millennium, the Great Firewall — the infrastructure that bans an ever-growing list of foreign websites — hadn’t yet been erected. Chinese citizens could access Facebook, Wikipedia and Google somewhat freely, and the state had yet to develop a robust mechanism to track sensitive words as a way to curb the spread of inconvenient information. By the end of the decade, scholars and writers debated public affairs on Weibo, a Twitter-like platform. Elsewhere, vibrant communities emerged around niche passions. The poet who writes under the name Xiaoyin remembers the new poetry websites of that era as chaotic and fun spaces. On sites like Poetry Life, his peers quarreled daily over matters like the possibilities of colloquial poetry writing. “Anyone could start their own bulletin boards,” he told me. “It was like bandits occupying hills and claiming to be kings.”

This internet-based community constituted a sea change for Chinese literature. Until the mid-1990s, jobs were assigned by the government. For generations of writers, membership in the state-sponsored writers’ association and staff jobs at party publications or state news agencies were more or less the only path to a career in letters. Some of China’s most prestigious novelists — like Yan Lianke and Mo Yan, known for their realist novels about the village life of their youth — published their debuts while serving in the People’s Liberation Army. But by the 2000s, such formal affiliations were no longer a prerequisite. Anyone with a computer and an internet connection could share his or her work on literary forums, where censorship was nascent and piecemeal. Free from the scrutiny of editors and censors, writers had a more direct relationship with their readers, who relished their refreshingly unabashed accounts of their historical moment.

Explaining the differences between these generations to me over the phone, the celebrated novelist who writes under the name A Yi borrowed concepts from classic martial-arts stories: Traditional writers, he told me, inhabited miaotang, or temples and courts, whereas writers of the internet age inhabited jianghu, or the unkempt natural world. Unburdened from the institutional gaze, they explored subjects and feelings that didn’t align with the state’s values. One essayist, writing under the name Muzimei, earned her reputation by publishing sex journals detailing her one-night stands and flirtatious encounters with rock stars and other public figures. If the era’s cosmopolitanism was thrilling, it was also morally ambiguous. Sometimes, upward mobility could engender a spiritual hollowness.

Without the relative freedom that the open internet provided, Hao might never have started writing. After testing into a university in Beijing and studying law, in 2000 he got a job in H.R. at a cosmetics company and moved to the southern metropolis Shenzhen — the heartland of Deng’s reforms. When Hao became a writer, he was an untethered man: His parents, who had been farmers in his rural home village, had both died by the time he was in college. He was briefly married in the late 1990s, but that relationship ended in divorce in 2000. Browsing one of the literature bulletin boards, he came across a serialized novel titled “My Beijing,” published under the pseudonym Drunken Fish. The story of a group of friends finding their way in the rapidly growing and suddenly wealthy capital inspired Hao to try his hand at a story that reflected his own time in China’s urban environments. “We wrote about the stories happening around us, our own anxieties, expectations and sense of rootlessness,” he told me.

Soon he had begun a novel about a recent university graduate in the southwestern city Chengdu navigating office politics and questioning his marriage. By April 2002, he was posting chapters to several bulletin boards under his new pseudonym: Murong Xuecun, a name reminiscent of a hero in a martial-arts novel. Eventually titled “Leave Me Alone,” the novel captured the hopes and delusions of recent college graduates who, like Hao, grew up in modest circumstances and now found themselves surrounded by temptations of fast cash and meaningless sex. Hao’s depiction of Chengdu’s seedy underbelly became a sensation on forums like Tianya, one of the period’s largest blogging platforms. Once, a colleague recommended the novel to Hao without knowing that he was Murong Xuecun. Within two months, he was approached by booksellers and publishers, and the novel came out that December. He enjoyed the spoils of success, frequently treating friends to fancy dinners and letting them borrow money when they needed it. Beijing is divided into six concentric rings radiating from downtown; generally speaking, the closer to downtown, the more prosperous the neighborhood. By 2010, Hao lived in a penthouse in the third ring.

Hao’s fiction tended to explore imperfect protagonists, abuse of power and the moral corrosion of city life. In his 2008 best-selling novel, “Dancing Through Red Dust,” the narrator, Wei Da, is a well-connected partner at a law firm who moves with confidence through gambling dens and corporate offices alike. Wei comes from a simple family, but in a world where money keeps everything in motion and compassion is weakness, his survival instincts and desire for influence overwhelm his better nature. In one scene, Wei runs over a poor farmer while driving drunk; in the end, the farmer is forced to pay Wei for damaging his car. Hao’s transition from a pulp-fiction writer to a daring documentarian and critic of the government was a natural progression. “From the get-go, he has been completely obsessed with how people are corrupted by the environment in which they live,” says Megan Walsh, author of “The Subplot,” a book about contemporary Chinese literature. In reading his work, she says, you come to believe that people can exist in and perpetuate “horrendous cycles of injustice.”

Authorities mostly viewed Hao and other newcomers with suspicion. At National Writers’ Association conferences, leaders urged “literature workers” to fight against “diversification of thought” — ideas that subverted authoritarian, patriarchal norms. Later, at a propaganda meeting, the deputy party secretary of Chengdu criticized Hao’s fiction for damaging the city’s image. A more “correct” local performance artist, Li Boqing, accused Hao of failing to present the city’s “mainstream features.” To him, Li said in an interview, Chengdu was “a beautiful, kind and tolerant mother, who also has a graceful figure.” Disgusted by the lust and greed portrayed in Hao’s work, Li insisted that writers should focus on the city’s relaxing atmosphere, famed history of brocade production and beautiful Chinese hibiscus.

As Hao went through a political awakening, that distrust turned into persecution. In 2011, Hao learned that his close friend Ran Yunfei, a scholar of classical Chinese, was arrested and charged with subversion after he warned that if China didn’t make reforms, it risked an upheaval like the Jasmine Revolution protests in North Africa. On Weibo, where Hao had millions of followers, he denounced the arrest and called Ran “the conscience of the country.” Ran was released from detention that same year, but Hao’s encounter with state repression radicalized him. “Until that point, I had enjoyed my life as a best-selling author and avoided getting into trouble,” he says. “But when their hands reached those close to me, I had to step up.” Hao’s writing steered to social commentary, and he began contributing to The International New York Times.

The repercussions were swift. Hao was banned from Weibo, and before long it became clear that he was blacklisted. In 2014, he started to receive invitations to tea — slang for informal police questioning. In the next few years, he had tea about 40 times, as often as once a month. Sometimes, as if they were old friends, officers would ask what Hao had been up to or what he had been thinking about. His writing career essentially came to an end: He never published another book in China, and he made his living by ghostwriting screenplays for movies and TV shows. When, out of habit, he reached for the bill while out at dinner, friends dissuaded him and insisted that he needed to think about his future. By the time he left China, he had rented a studio apartment outside Beijing’s fifth ring. Thirty-six of his friends — writers, scholars, activists and lawyers — had been detained or sentenced to prison. Late at night, as he fell asleep, he wondered when his turn would come. “I didn’t have long-term plans,” he says, “because I felt that I had one foot in prison already.”

Under President Xi Jinping, who took office in 2013, the Communist Party has sought to assert China’s position as a rising global power. Domestically, Xi’s government has shown less tolerance for the kind of writing that Deng’s reforms fostered and has been keen on creating a centralized discourse that nurtures national pride through an emphasis on “telling China’s story well” — a piece of ubiquitous political boilerplate that Xi introduced into the national consciousness. In the spring of 2013, less than two months after Xi became president, state outlets reported on a party central document that instructed cadres to prioritize “the struggles in the ideological sphere” and to “reinforce our management of propaganda on the cultural front” and “cut off channels of erroneous ideologies and speech at their headwaters.” This course correction was a tacit admission that Deng’s Opening Up policy stoked growing conversation about notions like feminism, queerness and civil rights — and that their discussion needed to be curbed.

To that end, the state has developed a robust surveillance and censorship apparatus. The guobao, local police officers, publishing authorities and digital surveillance tools are all mobilized into a multifaceted operation whose purpose is to control “China’s story.” That machinery has transformed the internet from a place of experimentation into Exhibit A of the state’s power. This often takes the form of a 404 error page — a notice that the state has deemed an article or a piece of social media content unfit for public consumption. No one is immune: In 2021, former Prime Minister Wen Jiabao published an essay remembering his mother, writing that China “should be a country full of justice and fairness.” On the popular social media app WeChat, users couldn’t share Wen’s essay on their timelines or private chats.

Xi’s approach has strangled free expression. According to Freedom House, which surveys internet freedom around the world by tracking control measures, the freedom of the Chinese internet has dropped by 40 percent since 2011, and for the last eight years, China has earned the ignominious distinction of being the “most repressive” among the countries that the organization monitors. In publishing, each new title requires individual approval, which can result in an exhausting process: Once a publisher decides to pursue a book proposal, it will be reviewed by in-house editors before they submit a request to the National Administration of Press and Publication, which decides whether the idea will materialize. In the last decade, the publication of new titles categorized as “literary” has decreased by 15 percent. Seven out of 10 literary titles published in 2013 were new works. By 2021, reprints made up half of publications.

In this environment of intense censorship and fractured cultural infrastructure, writers must be flexible, willing to forgo old forms and move fluidly among genres if they want to continue making meaningful work. Journalists become serial entrepreneurs who dream up new ways of creating to fill the lacunae they see. When one project becomes infeasible, they move on to another.

Zhang Wenmin, a veteran journalist who writes under the name Jiang Xue, became known for her coverage of a 2002 civil rights case in which four policemen showed up at a newlywed couple’s home because they were watching porn. Among many colleagues, there had been the consensus that no matter what, they had to try to say a little more, Zhang recalls. Sensing increasing pressure, she quit institutional journalism in 2015 to become a self-publishing blogger. With long, straight hair, Zhang dresses simply. In contrast to the steely insistence on common sense in her writing, there is a vulnerable shyness in her physical presence. “I’ve never been cool,” she joked softly, her arms draped in front of her body. On WeChat, she wrote stories about dissidents, something no news outlet would allow, she said, because it’s like violating a tiantiao — a statute sent from heaven. She was uninvited from journalism events. She lost her Weibo and WeChat accounts, becoming virtually invisible. “Friends and family think I went too far,” Zhang said. When her city, Xi’an, went into lockdown, a friend offered her own WeChat account to publish Zhang’s journals. They went viral but also drew attacks. “The worsening media environment in the last 10 years makes people see things upside down,” she said. “When you do the most normal thing, it appears abnormal.”

Elsewhere, an even more bottom-up kind of writing community appeared. Its participants are assisted by affordable technology — three-quarters of the Chinese population are smartphone owners — allowing a wider swath of people to publish more varieties of writing. While Hao’s generation of writers was predominantly middle class and upwardly mobile, the spread of internet-enabled technology has allowed working-class people without degrees to pursue literature. On social media platforms like Kuaishou, where users post short video clips, factory workers, masseuses and truck drivers started to compose poems. In 2017, a 44-year-old single mother, Fan Yusu, became a literary star almost overnight after her autobiographical essay, “I Am Fan Yusu,” went viral on WeChat. Beginning with a striking line — “My life is a hard-to-read book: Destiny bound me poorly” — it narrates her rural youth and eventual employment by an uber-rich Beijing businessman who hires her to take care of the child he shares with a mistress. Six days a week, she leaves her own daughters behind and attends to the love child. She started writing in her free time because, she thought, “to live, you have to do something besides eating.”

The journalist and editor Yang Ying has been a champion for overlooked stories and the platforms that host them. She has managed to build a successful career despite cycles of setback and rebirth: A former reporter for a business weekly, she left that magazine in 2014 after growing dissatisfied with conventional media. Along with a couple of other editors, she started a popular digital outlet whose name translates to Curiosity Daily that covered subjects like the Shanghai Pride Parade, a Texan who moved into a dumpster for a year to explore sustainable living and the work of the Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda, who once commented that creators should keep influence of the state at bay. After the authorities suspended the outlet twice for “illegally building a news gathering and editing team,” the outfit dissolved in 2019. Yang persisted, following that project with a digital magazine called Xiaoniao, or Little Birds, in which she published literary writing on subjects that could no longer be explored in journalism. “Literature is our last refuge,” Yang told me.

“In stories, people can communicate with one another,” Zhang Jieping, a journalist turned media entrepreneur and founder of the fellowship Zaichang, or “On the Scene,” told me. “Their joys and sadness become relatable. With today’s news outlets, it’s increasingly hard to achieve that.” As journalism institutions collapsed, Zhang built Zaichang to create a community and a ladder for aspiring journalists to learn to tell such stories. Editors like Yang and Zhang want to correct that dearth of connection by normalizing what Yang called “everyday messiness” — topics that the state considers counterproductive, like disappearing traditional villages and the rising diagnosis of anxiety in the aftermath of disasters. In Xi’s China, though, publishing this work means courting unwanted attention. During Shanghai’s Covid lockdown, Xiaoniao published a special edition that collected haunting real stories, including one about a young woman who evaded the rules to cross the city to see her critically ill father. Soon, Yang was treated to tea by her local police. Apparently swamped with tea appointments, they asked her to remove the entire issue from the publication’s mobile app. She complied.

Without public distribution channels, the special issue of Xiaoniao lives as a PDF passed around among friends. “I have no idea how far it has reached,” Yang said. “There is something samizdat-like to it,” she said, referring to the underground literature of 20th-century Eastern Europe, which circulated hand to hand. In today’s China, people create knowing that publishing is transient in nature — online articles can be taken down; books can be removed from the shelves; writers can be blacklisted; bloggers can be “disappeared.” (One of the websites Xiaoyin frequented, Poetry Life, announced its shutdown on July 13. “Poetry Life was born on the internet where it will dissipate,” the announcement read. “It has been a mirage as well as our real land.”)

Yet many people go on writing in whatever capacity they can manage. “If the goal was to escape censorship, then we wouldn’t be in this business,” Yang said. They focus, instead, on creating a new possibility of public writing: a vibrant, breathing thing. “Here, people are quick to forget,” she said. “Sometimes they are forced to forget. Other times, new events overwrite the old before you know it. It’s like we live in an environment where people can’t keep going if they don’t learn to forget.” She paused to search for the precise words. “Literature is a good way to help people remember things.”

Earlier this year, Zhang Wenmin and Hao were introduced by mutual friends and met while they were each traveling. Pondering her future, Zhang was both curious about and daunted by the examples of Hao and other expatriate writers. At a dinner with other Chinese writers, she spoke almost to herself. “How does a writer come to accept their status of exile?”

In Melbourne, Hao is curious about his new surroundings. Every experience presents opportunities for discoveries: After contracting Covid and speaking with a public-health official on the phone, he was prescribed free medication. “Isn’t this socialism?” he wondered. He went to observe a local election and chatted with people outside. “It’s eye-opening,” he says. “There is a party representing sex workers. There is also a party for animal rights.”

Hao is eager to master his new language but is baffled by the choice of other exiled writers, like the late Milan Kundera, to abandon their mother tongues in their work. The act of writing — of making sense of one’s experiences — is so bound up in the language a person speaks, along with all the little intricacies and inexplicable imagery within it. To abandon it is almost like abandoning yourself. He told me the story behind his favorite Chinese phrase: huangliang yimeng, or “a fleeting dream as the golden millet cooks.” It refers to a story in which a young man falls asleep at an inn as the innkeeper steams a pot of millet. In his dream, the man marries a beautiful woman from a wealthy family, rises to power in court politics and narrowly escapes death after jealous rivals set him up. After a lifetime, he wakes up. The millet isn’t done yet. Which is the reality: eventless destitution or surreal splendor punctuated by viciousness?

Hao has readily joined a growing community of Chinese activists and writers in exile. “As the environment grows dire,” he wrote to Zhang on Signal, the encrypted messaging service, “we are a generation that’s destined to be uprooted and scattered, to drift through the world.” Privately, though, Hao is still processing the past. Since self-exiling, Hao has experienced a measure of survivor’s guilt. His tally of arrested friends has risen to 41. Last fall, when thousands of citizens protested the arbitrary Covid policies, Hao had an intense feeling of missing out. One day, perhaps, he thought, he would decide to return home as abruptly as he left. In his early essays, Hao depicted himself to be a somewhat feeble man. When he encountered physical conflict in the streets, he tended to avert his eyes and avoid getting involved. It’s different, however, when the conflict is intellectual. He finds himself oscillating between wary caution and reckless bravery. He cannot stomach the government’s authoritarian grip on China’s literary culture and public life. “Who gives you the right to rule this way?” he wondered aloud.

Last year, Hao began writing fiction again at the age of 48. He is in the middle of a new novel he is calling “Homeless Dog.” The working title is inspired by a friend’s experience during a tea session when a guobao officer scolded him: “Don’t fancy yourself to be some kind of big figure. To me, you are merely a homeless dog.” Seen in this light, the title poses a question: Who gets to define writers like Hao? “I had to make many difficult choices, but I’m proud of the life I lived,” Hao says. In May, he was touring for his Wuhan book in Norway. In drizzling rain, on a train passing through unfamiliar cities, he dozed. A dream came: He was 18 again and about to take the college entrance exam. He was feeling unprepared. He woke up feeling jittery, then remembered that the old days are long gone. He is far from home.

Han Zhang is a journalist on The New Yorker’s editorial staff. She has written about the political and literary narratives that have shaped Chinese culture and identities. She is also the editor at large for Riverhead Books, where she is working to introduce contemporary Chinese-language literary works to English readers.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.