In Texas, animal shelters are obliged by law to ensure that their ambient temperature does not rise above 85F (29C) for more than two hours, a measure designed to protect dogs and cats from extreme heat and provide for their “health and wellbeing”.

If only humans were so lucky.

Across the state, in prisons that have no cooling systems, up to 100,000 incarcerated people are baking in concrete and metal cells that act as heat traps. Inside temperatures are estimated to rise regularly above 115F (46C), and have even been recorded to reach as high as 149F, pushing individuals to the point of mental or physical breakdown, or even death.

With Texas set to enter the hottest part of the year over the next two weeks, and with a brutal climate-crisis-fuelled heatwave pummeling the US south, conditions inside its dilapidated and overcrowded penal institutions are reaching crisis point. Inmates have told the Guardian that they are stuck virtually around the clock inside cells they described as ovens.

“Sir, have you ever seen what the heat does to a dog?” Luke Pryor, 39, a prisoner in the Wainwright unit, which has air conditioning, wrote from his cell in an email. “We are trapped in here and it’s driving people insane.”

Raymond Gonzalez, 48, described daily life inside Ferguson, one of the oldest prisons, which also has no cooling. He called his cell an “oven” and said he was allowed out of it only twice a week for an hour at a time.

The hot sun beams into his cell all day, he said, and when he or his fellow inmates try to block its rays by covering part of the front of their cells, they are issued disciplinary tickets for obstructing the guards’ view. “To try and remain cool I have to walk around in only my boxer underwear, pouring sink water all over my head and body.”

At night he soaks a bedsheet in water, places it on the concrete floor which he also wets, and lies on it. That’s the only way he can sleep.

The impact of heat stress is evident in his and others’ behaviour. “I get angry and frustrated way too often and too easy,” he wrote in an email to the Guardian. “The mental and physical fatigue is driving me crazy. Sadly, you see inmates losing it and fighting their cellmates out of agitation caused by these conditions.”

Texas is one of at least 13 states without universal prison air conditioning. About 70% of its units have partial or no cooling systems.

Amite Dominick, president of Texas Prisons Community Advocates (TPCA) which works with inmates and their families, estimates that at capacity there would be more than 100,000 inmates baking in dangerously hot cells.

The Texas department of criminal justice (TDCJ) has been mandated to take temperature readings inside cells every day in the summer months. The latest figures obtained by the Texas Standard show levels rising to 106F in some units last month, but Dominick suspects that the measurements are set up to minimise the extent of the crisis and that the real heat levels might be much higher.

“They are not being honest with this data. People are dying because of the heat, and still the agency is refusing to acknowledge that it is even a factor,” she said.

The TDCJ insists that there has not been a heat death since 2012. This year official data records only eight incidents of inmates requiring medical care for heat-related injuries, none fatal.

That jars with academic and other studies, as well as with the experiences of inmates and prison staff. Last year a team led by Brown University analysed the more than 2,000 deaths that were recorded in uncooled Texas prisons between 2001 and 2019 and concluded that 13% – some 271 deaths – might be attributable to extreme heat.

In the current heatwave, the Texas Tribune reported that at least nine inmates had died since mid-June in prisons without air conditioning. The cause of death was noted as heart attack or cardiac arrest or indeterminate, but in each case outside temperatures soared above 100F on the date of death and were almost certain to have been much higher inside the cells.

“We take numerous precautions to lessen the effects of hot temperatures for those incarcerated,” a TDCJ spokeswoman said. She said that everyone had access to ice and water, fans are strategically placed to move air around, and the number of cooled beds available has been increased.

But the department’s efforts, including $85m that has been earmarked largely for maintenance of those cooling systems that do exist, appears not to have reached many inmates sweltering in their cells. Jose Guadalupe Lucio, 45, wrote to the Guardian from Ferguson prison that in just the past week his row had called “man down” three times, after inmates collapsed from heat exhaustion.

“A lot of times we have to make a commotion to get the attention of the CO (correction officer) so they can come check and pull the inmate out.”

Severe staff shortages across many Texas prisons further exacerbate the problem. The Coffield Unit, for instance, is down to below 40% of its normal staffing levels.

With too few guards on duty, inmates complain that there are fewer respite periods out of their cells, showers are limited to three a week, while prisoners who experience medical emergencies from the heat often wait for help to arrive. It is common, inmates said, to go for six hours at a stretch without seeing a staff member.

“It takes a toll on the mind big time,” Lucio said. “One has to have a strong mind to be able to take this, ’cause it kinda gives you a hopelessness feeling when we can’t do nothing to deal with the heat.”

So far this year there have been 28 suicides in Texas prisons – well on track to exceed last year’s total of 52. Brittany Robertson, an outside representative for inmates, has analysed official data showing the rate of assaults between prisoners and between prisoners and staff.

She found that violence goes up in the hot summer months, and is notably more prevalent in units that are uncooled compared with those with air conditioning.

“There is a level of desperation that can cause aggression that comes from having to battle just for basic necessities in the heat such as a shower,” Robertson said.

Inmates are not the only ones to suffer. For correction officers, burdened with thick uniforms and stab-proof Kevlar vests, the heat is also a torment. “I would say the heat has more effect on staff than on inmates,” said Jeff Ormsby, executive director of the Texas correctional officers’ union which represents 23,000 prison staff.

Ormsby said that many officers quit in the summer months, returning in the fall when the prisons are cooler. That creates a vicious circle in which staff shortages inflame tensions inside the prisons, making the heat even more unbearable, thus pushing further staff to leave.

The end result is a broiling cauldron of heat and emotion. “The heat triggers violence, tempers are short. People are miserable inside prison, in the heat, and it becomes a lot more dangerous,” Ormsby said.

Asked why in his view the state hasn’t acted to break the cycle, Ormsby replied: “They just don’t care.”

The Guardian asked the TDCJ why it had not requested state funding to introduce AC into all its prisons. The spokeswoman did not answer the question, but said: “We are committed to do all we can to keep staff and inmates safe.”

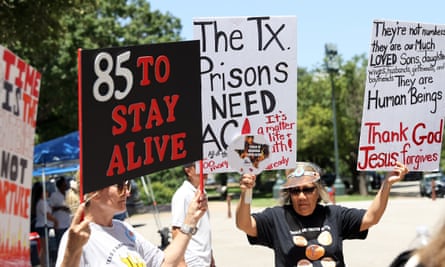

Legislation has been introduced to the Texas state legislature since 2019 that would provide funds to introduce AC to the units. Each time it has come up for debate it has been stymied in the Republican-controlled state senate.

This year the Texas house passed a bill that would invest more than half a billion dollars in air conditioning. The senate opposed the idea, and, despite the state having $33bn in reserve, opted instead for a different amount of investment: zero dollars.

Carl Sherman, a Democratic state representative who has sponsored cooling bills, said state senators remained stuck on an old mindset. “The perspective was that if you do the crime, you should do the time – we should not make those we incarcerate comfortable.”

Sherman said that the fact that the bill passed in the house showed that a shift in that mindset was possible, including among several house Republicans who voted for it. Empathy could be extended to the thousands wilting inside baking cells.

“It is true that prisons should not be the Hilton or the Marriott hotel,” he said. “But they should be humane. When inmates are begging and pleading for their lives in the searing heat, that is a problem.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.