BERLIN – Artist Itamar Gov is surprisingly laid back, considering his frenetic life story and his provocative art. Among the subjects of his work are Nazism, the Nakba, chemical weapons and marginal subjects from history that he calls “microhistory.”

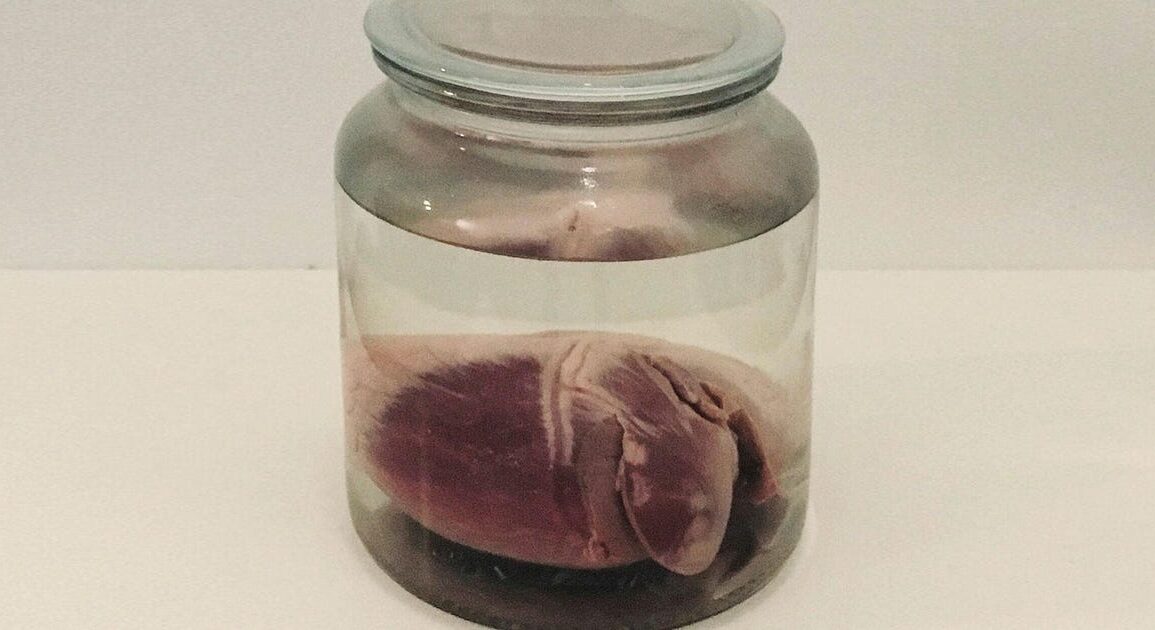

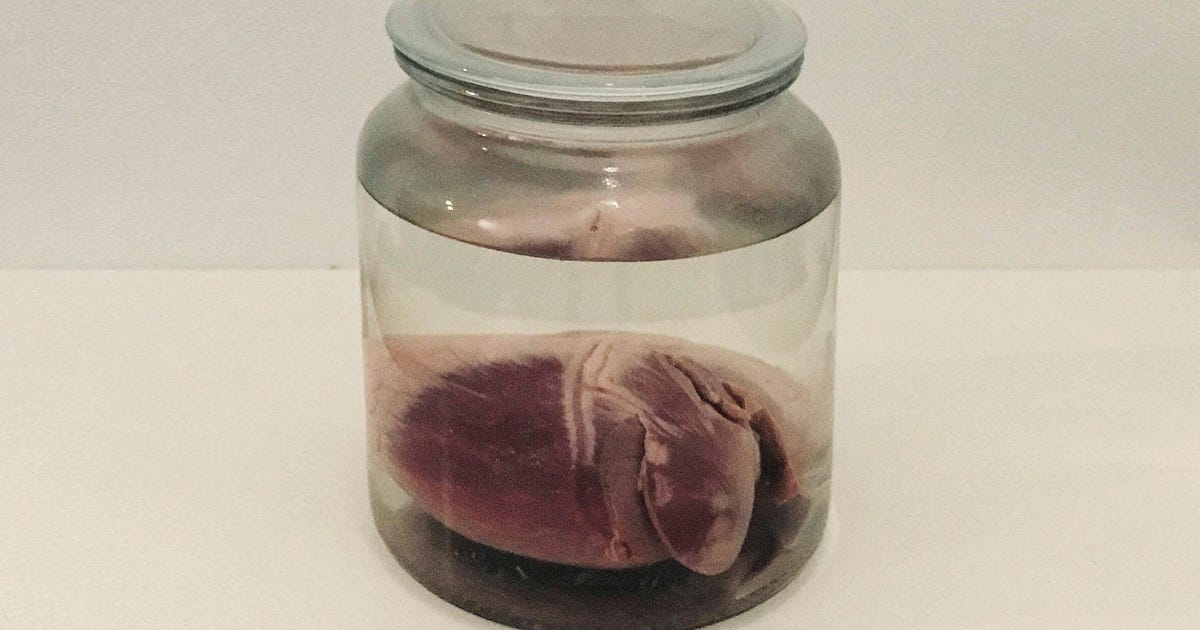

He titled one of his works “Hitler’s Heart,” but he has not yet found the right place to exhibit it. He currently has a solo exhibition running in Berlin, and is also participating in group exhibition in that city. Next month, he will open another solo exhibition in Mannheim.

How does he explain the divide between the sense of ease he evokes – including his tendency to blush – and his inflammatory art and the constant changes in his life? He replies, with a shy smile, that calm is essential for balance. “Maybe the works are an alternative to interpersonal communication. I get embarrassed pretty easily in interactions with people, and it helps that I can put something into space and not be there to communicate it.”

‘It’s a dark day in Israeli history and I don’t see a way back,’ says former U.S. ambassador

Gov left Israel 13 years ago, at the age of 21. He studied film, history and literature in Berlin, Paris and Bologna, has mastery of six languages. About two years ago, he transitioned from working as a curator – with Documenta 14, at the House of World Cultures in Berlin and the Fondazione Adolfo Pini in Milan – to becoming a full-time artist.

His famous surname also weighed heavily on him in Israel. No, he is not the son of performer Gidi Gov, but his nephew – he is the son of producer Michael Gov, Gidi’s brother, and visual artist Neta Gov. His younger brother is Uri Gov, who has recently garnered fame as the lead actor in the television series “Carthago,” and his younger sister – Uri’s twin – is Aya Gov, an artist and product designer. “I have a pretty strong suspicion that people will think that people worked things out for me, that my achievements depend on favors and shortcuts because of the family,” he says. “ In Berlin, and in other places I’ve lived since 2010, that risk isn’t there.”

‘There’s something natural in Jews being immigrants. That’s Jewish history – when you have to get up and leave, you leave. The most interesting stories about Jews throughout history are stories of wandering.’

Life in Berlin suits him. “This is a city where everyone is foreign. Even the Germans come from all sorts of places in Germany, and I don’t feel like I’m being judged when I walk down the street. And there’s a lot of space to do things here. In Paris, I felt like a stranger, even though I speak French. Paris is a rich and interesting city, but there’s a sense that everything is frozen there. It isn’t open and inviting like Berlin.”

We’re just the third generation of immigrants in Israel, and we already want to move again. Do you think that is our fate?

“There’s something natural in Jews being immigrants. That’s Jewish history – when you have to get up and leave, you leave. The most interesting stories about Jews throughout history are stories of wandering. Those who survived in the period before the Holocaust were very often the ones who knew when to leave and escape. And with no connection to history, when you leave Israel, you put things into perspective. They educate us to grow up in Israel feeling like it is the most intelligent, important and relevant place in the world, and then you realize it isn’t. I remember what a shock it was for me in Paris to meet Jews who weren’t interested in Israel. There are still more Jews living outside of Israel than in Israel, and it’s not the only option for Jews in the world.”

Indeed, it is easy for him to engage with subjects that are less popular in Israel. “It feels like it wasn’t acceptable to deal with Jewish history in Israel over the years, because it was taken for granted that we are Jews and we don’t question the Zionist narrative. Primo Levi wasn’t exciting enough and anyone who goes to Poland gets a book by Ka-Tzetnik.”

These thoughts led him to put together the German-language book “Ein jüdischer Garten” (“A Jewish Garden”) that was published a few months ago – a collection of Jewish experiences, ideas and memories by means of 160 works of literature from different periods, languages and places. “I worked on the book for four years with Hila Peleg and Eran Schaerf, and it’s camouflaged as a plant guide in alphabetical order – only instead of botanical information about apple, willow and poppy, there are literary excerpts in which these plants are mentioned and information about the hardships of the people who wrote them. Israel and Hebrew are part of the book, but aren’t central.”

Do you not have any connection to Israel?

“I come for visits, and I have only one passport, and it is Israeli. I am here in Germany on an artist’s visa. That is the essence of my connection. But my whole adult life has been here in Berlin. I have never been involved in anything in Israel. Not that I’ve declared this, it just happened. My family background as an Israeli and a Jew is, of course, present in my work, and I don’t deny it.”

Where did your obsession with depicting the Holocaust and Nazism come from?

“My mother’s father, who was born in Warsaw in 1926, managed to survive the war years with a Christian identity. He escaped from the ghetto after his parents died of typhus and bought forged papers showing that he had been baptized as an infant. As a Christian Pole, he was conscripted into the German army, and so that no one would discover he was circumcised, he volunteered to guard an arms cache in a forest, something that no one wanted to do. Later on, he escaped and joined the partisans, discovered that he had attached himself to an antisemitic group that was looking for Jewish partisans in the forest, fled again and joined another group. When the Russians arrived, he was sent to prison as a Polish partisan. He went back to Warsaw and tried to re-establish his life there and registered for law school, but that failed. Even after the war, the Poles didn’t like having a Jew in their class.”

At a certain point, his grandfather started working as a sailor in European ports, until he joined an illegal immigrant ship and later became an officer in the Israeli navy. David Ben-Gurion did not like his Polish surname, Vishnevsky, and, as part of a process of Hebraizing the names of Israel Defense Forces officers, it was changed to Sharon.

“My grandfather’s story is always with me – the whole issue of identity and pretending to be someone else, of being part of a group or observing from outside, the thought that there are superior and inferior races and the desire to deceive everyone into believing that you are part of the superior group, in order to survive.”

From Zeus to Dolly the sheep

Gov’s solo exhibition at the Zilberman Gallery in Berlin is titled “Chemistry and Physics in the Household.” The strange name was borrowed from a lecture given in 1901 by the chemist Clara Immerwahr, who was born Jewish but converted to Christianity, that same year, she married the Jewish chemist Fritz Haber, who in 1918 won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. “I found an advertisement in a newspaper and the title intrigued me,” says Gov. “I asked myself what it meant, chemistry and physics in the household, and I discovered only that the lecture was held at a women’s club in Breslau” – the city where the couple lived, today Wroclaw in Poland. Gov looked into the couple’s estate and mostly found mysteries.

One of the mysteries concerns Immerwahr’s death. She committed suicide in 1915 with a pistol shot, two days after the successful trial of her husband’s newest invention – the development of a chemical weapon. In the second Battle of Ypres in Belgium in World War I, Haber himself supervised the use of poison gas that the German army deployed against Allied soldiers, which led to tens of thousands of casualties. After his wife’s death, Haber aided in the German attack on the Russians.

One claim is that Immerwahr committed suicide because of her objection to the use of chemical weaponry, but this is uncertain, and she may have killed herself because she, unlike her husband, went unrecognized. After the war, Haber moved to Switzerland to escape being tried for war crimes, but went back to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Germany, where Zyklon A was developed. It was used initially as a pesticide, but was subsequently developed into Zyklon B, which was used as a weapon of mass murder several years after Haber’s 1934 death in Switzerland.

Immerwahr’s lecture was the starting point of the creation of a branching and seemingly random flowchart of historical events that Gov connects. Among them are the “Splendor Solis” book of alchemy written by Salomon Trismosin in the 16th century; Mary Shelley’s book “Frankenstein” from the early 18th century; Leni Riefenstahl’s 1938 film “Olympia,” which delves into the obsession with the perfect human body; and the discovery of the Prussian blue pigment in 1704, which is also the color obtained when mixing Zyklon B with plaster surfaces – and the medicine approved by the World Health Organization as an antidote for heavy metal and radiation poisoning.

The flowchart is the basis for four installations at the Zilberman Gallery, which, unlike its Israeli counterparts, is not a clean white cube, but rather a space with a natural wood flooring and walls that have been painted, of course, in Prussian blue. The central installation, “Olympia (COR.145-PED.510)” consists of a metal operating table with many white statues of body parts cast from Gov’s body or sculptures by artist Arno Breker, a major sculptor during the Nazi period, who created what the Nazis considered “German art.” On the upper part of a metal operating table are the torso of a muscular man, and, on the bottom, a mix of body parts – buttocks, feet, internal organs, women’s breasts and eyeballs.

Also in the space is the object “Amalthea 717.” In Greek mythology, Almathea is the goat that suckled Zeus. In Gov’s view, the object is the electro-mechanical sibling of Dolly the cloned sheep, with posable metal limbs and real sheepskin laid on top. Gov’s explanation is detailed and circular: “Amalthea is a kind of adoptive mother, and it’s also the name of one of the moons of Jupiter; 717 is the number of minutes it tales the moon to circle around Jupiter, and heavenly bodies and space programs are given Greek names. The idea was to show how much all processes and inventions are mixed together and interdependent – it is impossible to separate alchemy from technological development, from race theory, from Greek mythology and from chemical weaponry.”

Gov has created a fascinating, alluring, and also quite crazy and bizarre space (in another installation, “The Nursery,” about 20 elliptical bodies are suspended in the air, resembling mummified butchered animals or massive cocoons). “Maybe it is a mad professor’s laboratory,” he says. “I’m suggesting a non-hierarchical and non-chronological view of more or less scientific events that took place in the past and will perhaps take place in the future. I am an artist and not a scientist, but in our era, when technology and science are breaking records every day, anything can happen.”

Gov’s obsession with Nazi history also manifests in a multi-channel video installation called “Breker CCTV” at the Kunsthalle in Mannheim. The installation relates to a list of artists compiled by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels in 1944, who were defined as “God-gifted” and central to Nazi culture. About 300 of the statues produced by these artists during the Nazi period are still standing in public spaces in Germany and Austria. The starting assumption of Gov’s work is that if they have remained in place, it has been decided that they pose no danger. Gov photographed 16 of these sculptures, and the installation acts as a control room that examines them and lets visitors decide whether they present a threat.

Gov got the idea for the installation from a fleeting coup attempt by extreme rightists in Germany. On December 7, 2022, 25 members of the far-right terror group Patriotische Union were arrested for trying to depose the German government and install Prince Heinrich the 13th, a member of the country’s minor hereditary nobility, as king.

“That was one of the most hallucinatory events that have happened recently. No one thought they would really succeed in staging a revolution and everyone considered [Heinrich] a clown. And then I asked myself, is he really just a clown? Do the actions of these groups really pose no danger? That brought me to the statues that are scattered throughout Germany, and to the fact that they’re not perceived as dangerous, that no one is going to become a Nazi because of them.”

This story corresponds with the disfiguring and removal of statues of Confederate leaders in the United States, and other figures throughout the world. “As I see it, taking down statues in the United States is fine and justified. Everything around us gets updated and refashioned, and the world rectifies injustices. There’s no reason to cling to symbols of oppression and injustice. In the case of those statues in Germany – that is a lot less clear-cut, because they don’t represent specific historical figures. I’m simply observing a situation and scratching a bit.”

How did you research the statues?

“A year ago, the German Historical Museum in Berlin did a project on artists from Goebbels’ list. There is now a detailed list and an interactive map of works by those artists. After the war, everything that was too ‘Nazi’ was taken down and disappeared, like statues that had swastikas on them. Sometimes a statue remains, and just the swastika was scratched off, so a small hole remains.

“What’s interesting about those statues is that these figures aren’t clad in anything ‘Nazi,’ but they symbolize the Nazi ideal of beauty, the imagined Aryan race. And because these statues are standing on public land, each municipality is responsible for them and has to see to cleaning them if there’s graffiti or stickers on them. There are municipalities that have decided not to clean the statues.”

Two of the statues are in the western part of the city, near the 1936 Olympic stadium. They are called “Die Siegerin” (“The Winner”) and “Der Zehnkämpfer” (“The Decathlete”), and were sculpted by Arno Breker, who was the undisputed star of Nazi art. Breker accompanied Hitler during the occupation of Paris and stood at his side in the famous picture in front of the Eiffel Tower.

The two statues are larger than life-sized, and they stand naked, shapely and broad-shouldered, gazing out at the horizon. Another sculpture is “Ring der Statuen” (“the Ring of Statues”) in Frankfurt, by Georg Kolbe, the second-most prominent artist on Goebbels’ list. He sculpted seven statues of naked and muscular men and women standing in a circle and gazing at the horizon, as well as at one another. Kolbe began working on them in 1933, and continued until his death in 1954, nine years after the fall of the Third Reich.

What’s so interesting about statues that are just standing there on the street?

“Since 1945, the Germans have occasionally convened committees and decided to leave them where they are. Germany knows to make changes in buildings or transform places into memorials. In this case, they’ve decided simply not to touch most of them. I don’t think that they necessarily have to be taken down, but it is interesting that so many naked people have been standing around in Germany for 80 years, and they decided that they’re not dangerous enough to get rid of them. It’s strange.”

Click the alert icon to follow topics:

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.