Many barrels of ink have been employed for the obituaries and assessments of Henry Kissinger’s life and legacy since his death last Wednesday at the age of 100. However, one story involving the former Secretary of State that might not attract as much coverage is nevertheless one of the most fascinating and revealing tales of its time: the accusation against the “Harrisburg Seven,” a group of antiwar activists, that they had formed a conspiracy to kidnap then-Secretary Kissinger in 1970.

In a 1972 trial, the federal government charged the defendants, most of whom were current or former Catholic priests or women religious, with a conspiracy that included the kidnap plot as well as plans to raid draft offices and bomb steam tunnels beneath Washington, D.C.

In November of 1970, F.B.I. Director J. Edgar Hoover first revealed the supposed conspiracy to members of a Senate Appropriations subcommittee, saying he had provided Mr. Kissinger with F.B.I. bodyguards to foil any kidnapping attempt. Attorney General John Mitchell repeated the bombing and kidnapping charges in his January 1971 indictment of the alleged conspirators. At first, the government sought life in prison for the members of the alleged plot, though by May 1971, prosecutors announced they were seeking only five-year sentences and fines.

F.B.I. Director J. Edgar Hoover revealed the supposed conspiracy, saying he had provided Mr. Kissinger with bodyguards to foil any kidnapping attempt.

While Philip Berrigan, S.S.J., Elizabeth McAlister, R.S.H.M., the Rev. Neil McLaughlin, the Rev. Joseph Wenderoth, Eqbal Ahmad, and Anthony and Mary Cain Scoblick were charged, a number of others were cited in the 1971 indictment as “co-conspirators,” including Father Berrigan’s brother and fellow activist, Daniel Berrigan, S.J., and Jogues Egan, R.S.H.M., the provincial superior of Sister McAlister’s Marymount order of women religious. Sister Jogues was briefly jailed for contempt of court for refusing to answer grand jury queries. Amid allegations that the F.B.I. had illegally wiretapped the Marymount order’s phones both at home and in Rome, she was released after three days.

The drastic reduction in the government’s initial ambitions led more than a few commentators to accuse Mr. Hoover and Mr. Mitchell of trying the case in the court of public opinion even though they knew that the charges of attempting to kidnap Mr. Kissinger would never stick. “The redrawn indictments clearly indicate that the government cannot prove the specific accusations leveled at the defendants by Messrs. Hoover and Mitchell,” the editors of America wrote in a Current Comment in May 1971. “Naturally, they also call into question the prudence and competence of those who authored the original charges.”

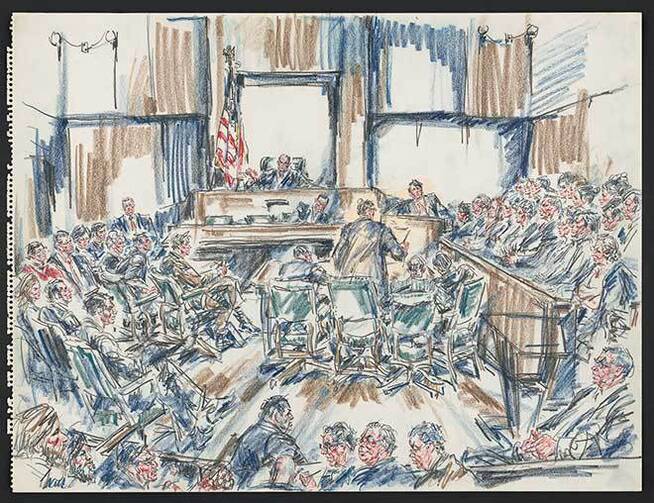

The trial began on Jan. 24, 1972, at the U.S. District Court in Harrisburg, Penn., with Judge R. Dixon Herman presiding. The defendants had a star among the lawyers on their side: former United States Attorney General Ramsey Clark, who told the court, “I am shocked that the United States Government should present such flimsy evidence. If I was still Attorney General I would never have permitted it to go before the grand jury, and you should enter a judgment of acquittal.”

The government’s star witness was Boyd Douglas Jr., a former convict described by The New York Times at the time as a “two time loser.” Mr. Douglas had met Father Berrigan in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary when the latter was still imprisoned on a six-year sentence for his role in the burning of draft records as part of the “Catonsville Nine.” (Mr. Douglas was in for pulling a gun on an F.B.I. agent when the agent attempted to arrest him for check fraud.) Allowed out of Lewisburg at the time to attend classes at nearby Bucknell University and work in a local library as part of the prison’s work-release program, Mr. Douglas soon became a go-between for the still-incarcerated Father Berrigan and some of his correspondents, including Sister McAlister.

Among the letters was one speculating that they should “kidnap—or, in our terminology, make a citizen’s arrest—of someone like Henry Kissinger.”

Because letters in and out of Lewisburg were read by prison officials, Mr. Douglas had two friends rewrite incoming letters into his school notebook, which guards normally did not check. According to a former associate warden at Lewisburg, the scheme didn’t last long before Mr. Douglas was caught, at which point he agreed to become a paid F.B.I. informant and started turning over the original letters to the F.B.I. He received over $9,000 from the F.B.I., including a $200 reward for information aiding in the capture of Father Daniel Berrigan on Block Island, R.I., in August 1970, after the latter had led the F.B.I. on a four-month “merry chase.”

Mr. Douglas was not an ideal witness for the prosecution: He had clearly agreed to the smuggling scheme as part of a deal with the government to avoid further incarceration, and his constant cajoling of the accused to come to Lewisburg to meet him and engage in further plotting created the impression of entrapment. Further, he admitted in his testimony that he gave the defendants Army manuals (provided to him by the F.B.I.) on how to build bombs, and encouraged them to use a gun to kidnap Mr. Kissinger—suggesting that the core of the government’s case was manufactured by the F.B.I. itself.

Among the letters presented as evidence was one from Sister McAlister to Father Berrigan speculating that they should “kidnap—or, in our terminology, make a citizen’s arrest—of someone like Henry Kissinger.” She envisioned releasing Mr. Kissinger—the bête noire of antiwar activists at the time—after a week in exchange for a promise to cease the aerial bombing of North Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, as well as the release of “political prisoners.” Father Berrigan responded to her in a letter from Lewisburg that her plan was “grandiose” and warned that such an action “opens the door to murder.” Mr. Douglas nevertheless claimed that Father Berrigan later told him of plans to recruit a team for the kidnapping.

After the prosecution presented its case, The New York Times later reported that lawyers for the Harrisburg Seven asked the accused if they wanted to pursue an active defense, given the optics of the case for the jury—a group of idealistic antiwar activists with no history of violence, including young priests and a nun, prosecuted for a fantastical crime for which they hardly had the means to commit—and the trial judge’s restrictions on what arguments they could use. Four of the defendants voted to rest and three (including Father Berrigan and Sister McAlister) voted to present a more active defense.

“I felt we ought to face squarely the violent absurdity of this indictment insofar as we could in this suffocating court,” Father Berrigan said in a news conference after the trial. “That we ought to submit to the requirements of truth, even toward the Nixon Administration, and that we owed people an explanation of our lives and resistance.”

In the end, Ramsey Clark did not call a single one of the defendants to testify. Rather, he simply stated, “Your Honor, the defendants shall always seek peace. They continue to proclaim their innocence. The defense rests.”

Ramsey Clark simply stated, “Your Honor, the defendants shall always seek peace. They continue to proclaim their innocence. The defense rests.”

After 59 hours of deliberations, the jury announced it could not reach a verdict on the conspiracy charge. After a hung jury was declared, the government declined to retry the case. Father Berrigan and Sister McAlister were convicted of a far lesser offense: smuggling letters in and out of prison.

America covered the trial in a long April 1972 essay by Evelyn Joseph Mattern, I.H.M., an Immaculate Heart sister and literature professor from Philadelphia who spent her spring vacation attending the trial, but otherwise gave it far less coverage than secular outlets like Time, The New York Times and The Washington Post.

In their 1971 Current Comment, “Kissinger Kidnap Plot Revisited,” the editors had expressed their disapproval of the government’s conduct in the case but also criticized “some segments of the peace movement” for harboring “a romantic fascination with quasi-terrorist activity.” The “plain people” of the United States, they wrote, “have no stomach for bombing and kidnaping, or even loose talk about such capers, no matter how well-intentioned.”

Father Berrigan and Sister McAlister were later married, and remained staunch antiwar activists in the following decades, with both serving significant prison time for their actions over the years. Father Berrigan died in 2002. His brother, Daniel Berrigan, S.J., died in 2016.

A personal note: When my grandfather, Michael Keane, a former mounted policeman in New York, died in August 1970, his funeral drew a large crowd to Incarnation Church in Washington Heights. The funeral program included art by Sister McAlister, who was in the same Marymount religious order as my aunt, Ellen Marie Keane, R.S.H.M. Years later, a relative of the family told my parents that on the way into the church for the funeral he had seen two men he recognized as former classmates from Fordham Prep parked on the street. When he stopped to say hello, they shooed him away in a hurry: They were F.B.I. agents, staking out the funeral in case Father Daniel Berrigan appeared.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.