There has been a pattern of increased activity in recent years at high-security detention facilities in Tibet, according to a new study measuring night-time lighting usage, suggesting a potential rise in harsher imprisonments by Chinese authorities.

The report, by the Rand Europe research institute, said the findings added rare new clues about the Chinese government’s “stability maintenance” policies of control in the highly securitised Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), which it described as an “information black hole”.

“Using overhead satellite imagery analysis and night-time lighting data, this study sought to add another piece to the puzzle in the hope of helping and encouraging other workers to complete the picture,” the report said.

The Rand study examined 79 detention facilities across the TAR, finding patterns of growth in night-time lighting were concentrated in the 14 higher-security facilities. They found increases across prisons in 2019-2020 and high-security detention facilities in 2021-2022. Growth in lower security facilities appeared to peak in 2017.

The light is seen from space and measured over monthly averages, and researchers said it could indicate new construction – as previous studies had found in Xinjiang – or the expansion of existing buildings, which was more likely in the Tibetan facilities. The study said growth in emitted light could also indicate increased occupancy or usage of facilities, without physical expansion.

The researchers believe the increased activity probably indicates a shift towards longer detentions, “similar to recent observations in Xinjiang” where up to 1 million people were estimated to have been sent to re-education facilities and high-security detention centres.

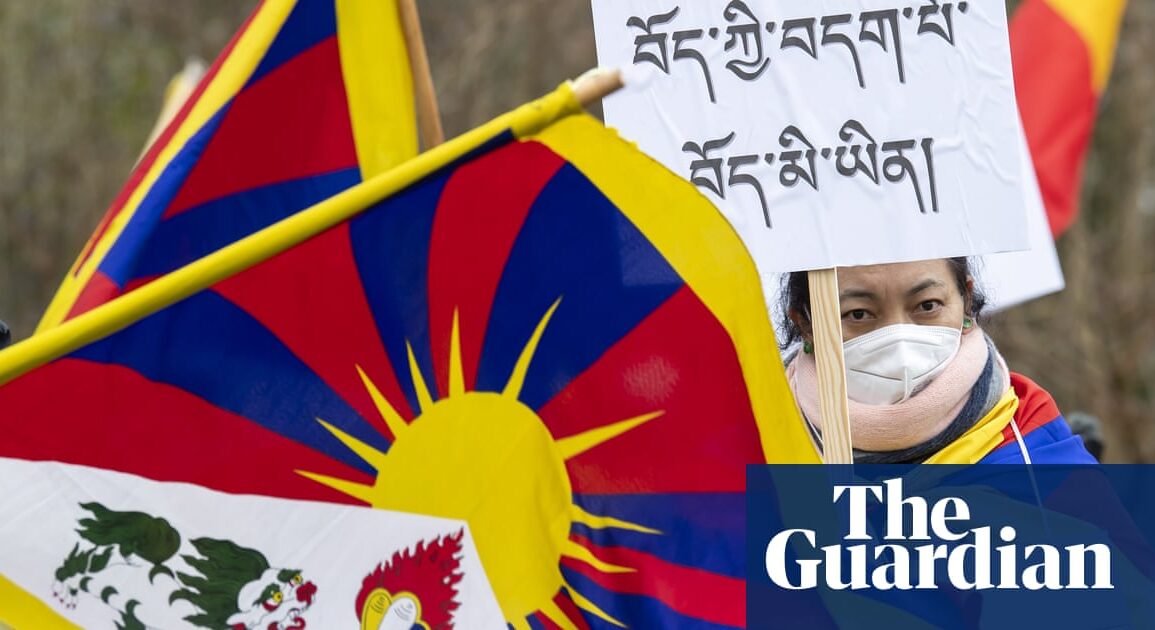

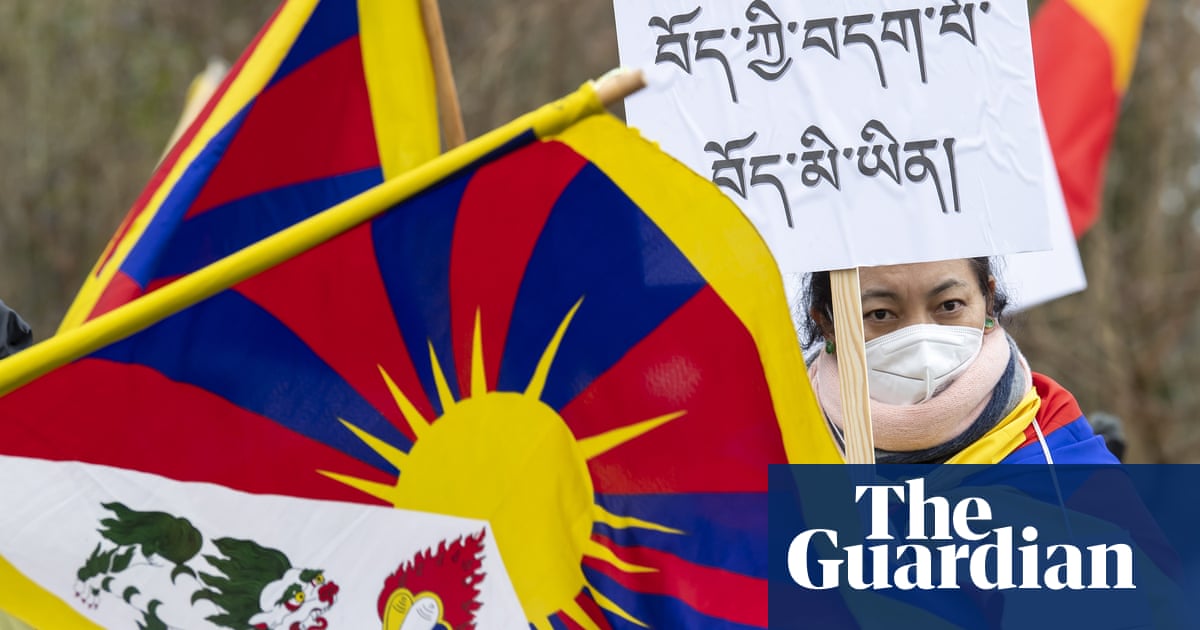

Tibet has been under Chinese control since it was annexed more than 70 years ago, in what Tibetans describe as an invasion and Beijing claims was a peaceful liberation from theocratic rule. It is among border regions including Xinjiang and Mongolia that are subject to long-running crackdowns on the religious and cultural practices of non-Han ethnic minorities. Government control accelerated after mass protests in 2008.

There have been successive waves of government crackdowns and what the report called “preventative repression” in the TAR, including the campaign against “underworld forces” launched in 2018 which targeted groups and individuals suspected of supporting increased Tibetan autonomy, organising over environmental protections and land acquisitions, and working to preserve Tibetan language.

Activists and human rights groups have expressed growing concern over the harassment, detention and torture of Tibetan activists, religious figures, and intellectuals, as well as mass surveillance of the population, and programmes of mandatory re-education and labour transfer. UN experts have also said about 1 million Tibetan children have been separated from their families and sent to state-run “boarding schools” in an effort to “culturally, religiously and linguistically” absorb them into the dominant Han society.

However, there is far less information from inside the TAR compared with other targeted regions such as Xinjiang, which analysts say is due to extraordinary controls on travel, communication and information, as well as a waning international focus on the government policies of control and oppression.

While researchers are confident there is continued and – according to the study – probably increased use of high-security detention facilities, the details of who is in there and why, and the conditions they face, remain unknown.

“Tibet remains an information black hole and any attempt to understand the security landscape there is fraught with difficulty,” Ruth Harris, the director of defence and security at Rand Europe, told the Guardian.

“Foreign researchers are blocked from accessing many Chinese sources and find much available data unreliable,” she added.

The report emphasised that a lack of information from Tibet did not mean a lack of repressive control, but highlighted the need for more research and greater international focus, on the level given to Xinjiang in recent years.

Tenzin Choekyi, a senior researcher with the UK-based human rights group Tibet Watch, said it was impossible to know what was going on inside detention centres and noted that the pattern of growth in night-time light coincided with the pandemic. The TAR reported just one case of Covid-19 before an outbreak in August 2022, but was subject to the strict and often punitive nationwide “zero Covid” policies.

Tenzin said there had been a steady decline in media coverage of Tibet in the last decade. She said this was in large part due to the lack of information flow, coinciding with travel bans and punishment of pilgrims crossing the border to India, and a pattern of reprisals and increased surveillance against entire communities for acts by individual activists.

She cited one instance of a Tibetan self-immolating in protest in 2015, which did not come to light until 2021. “That is the level of fear of Tibetans inside Tibet about sharing those stories,” she said.

“Because of the information delay and disarray, it’s difficult to tie a coherent narrative together of what’s happening in the TAR.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.