Yelena Sannikova has been writing letters to political prisoners since she was a Soviet teenager in the 1970s. Almost half a century later, with the Russian state’s long, harsh clampdown on dissent intensifying further amid the war against Ukraine, she is as busy as ever.

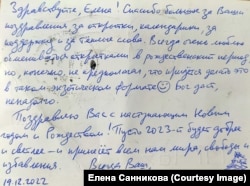

A poet, translator, publicist, and dissident who was jailed and sent into internal exile in her 20s, Sannikova has dedicated much of her time to writing letters and postcards to prisoners — “tiny greetings from the free world,” she calls them — and providing other essential support to people she believes have been put behind bars for their political activism or their ideals.

“When I was in prison myself, I learned what confinement really is and how important letters are when you are there,” she told RFE/RL’s Siberia.Realities. “When I was in exile, I got letters from strangers, and I know how much support and help they provide. So, today, I consider it my obligation to write to prisoners.”

According to the now-banned human rights group Memorial, the number of people designated as political prisoners in Russia has tripled in the last five years, reaching 554. Since Moscow invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the ranks of the repressed have been swollen by dozens of people sentenced for anti-war activity and statements, as well as for purported “treason” or “justifying terrorism.” Dozens more are currently under investigation or being held pending trial on similar charges.

On July 16, Sannikova mailed 23 letters to prisoners — “with postcards, cute stickers, and good wishes.” Over the years, the number of cards and letters she has sent has mounted into the thousands.

“Now, when the number of political prisoners is very high, it isn’t possible to write to everyone,” Sannikov, 63, conceded. “But you can try to involve friends and acquaintances. I am very happy to see that more and more initiatives of this type are popping up. People understand that prisoners need words of support.”

‘Darkest Before The Dawn’

“Tomorrow is the first day of summer,” reads a letter that recently arrived from respected historian Yury Dmitriyev, who is serving a 15-year sentence that his supporters say is retribution for his groundbreaking research into the crimes of Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, “but the flies and mosquitoes have already been chewing up the poor prisoners for about three weeks.”

“We live a little more peacefully here than those of you outside the walls,” Dmitriyev continued. “At least we have some clarity — a sentence, a beginning, an end. But you never know when and from where they will come down on you. But just the same as you, we are waiting for an end to all this.

“I hope you survive the ‘terminal stage’ of the Putin regime,” he concluded. “Take care.”

Sannikova says she is impressed by how many prisoners maintain their optimism and, like Dmitriyev, try to comfort those outside the prison walls. In this context, she mentioned opposition politician Vladimir Kara-Murza, who was sentenced to 25 years in prison in April after being convicted of treason and other crimes over his criticism of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“He writes a lot,” Sannikova said, “saying not to lose optimism and hope.”

In June, Kara-Murza said prison authorities were illegally preventing him from receiving letters.

Ilya Yashin, another opposition politician who is serving an 8 1/2-year sentence for his condemnation of the invasion of Ukraine, recently wrote a similar message on a postcard from captivity.

“Thank you for your sincere and warm message,” he wrote. “I really liked it. Preserve your optimism and your faith in people. The night is darkest before the dawn. All will be well, Ilya Yashin.”

‘Collision With The System’

Sannikova first learned of the existence of political prisoners in the Soviet Union from foreign radio broadcasts when she was a schoolgirl. As a teenager in the 1970s, she met the family of imprisoned dissident Kronid Lyubarsky, and they first told her that it was possible to write letters to such prisoners.

“He received quite a lot of letters, and I added my modest contribution to that flood,” she said. “The letters arrived, and he mentioned them in his letters to his wife. At a certain point, I got bolder and began writing my opinions in the letters, which only led to them being confiscated and to trouble for me at school and with the local authorities. I was in the ninth grade then and didn’t quite understand that this was my first serious collision with the system.”

After Lyubarsky was released and expelled from the Soviet Union in 1977, he began publishing information about Soviet political prisoners, including how to write to them.

“In the 1980s, his list became a guide for me as I undertook the work of collecting information about prisoners and trying to help them,” Sannikova said. “I used this list when I gathered friends around New Year’s or Easter to send a large number of cards to prisons, labor camps, and places of internal exile.

“We selected pretty cards and wrote kind words, good wishes, and three or four of us would sign each card,” she recalled.

Sannikova later learned that such efforts sometimes had an enormous effect. Gleb Yakunin, a dissident priest who was imprisoned for seven years in the 1980s, never forgot the letters he received.

“Almost to the end of his days, whenever he saw me, he recalled how our cards cheered him up in prison and asked about the fates of those who signed the cards with me,” she said of Yakunin, who died in 2014.

In 1984, the KGB arrested the 24-year-old Sannikova and held her in Moscow’s Lefortovo prison, whose inmates today include people arrested by the KGB’s main domestic successor, the FSB. She was later sentenced to a year in prison and four years of Siberian exile for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.”

“I continued writing to political prisoners even while I was in exile,” Sannikova said. “I also corresponded a lot with other people in exile.”

During her time in prison, Sannikova herself received many letters from strangers abroad.

“I don’t know how these people found out about me, but I imagine they were members of Amnesty International and other such organizations,” she said.

She returned to Moscow at the end of 1987 and resumed her human rights activity — and continued writing letters to political prisoners.

‘The Promise Of Change’

To this day, the work remains largely the same — a group of four or five friends writing birthday greetings or congratulating prisoners on various holidays.

“I love to buy postcards with classical paintings from museums,” she explained. “Also landscapes with pretty views of cities. After all, in a cell there is nowhere for the eye to rest.”

She also includes such items as envelopes, paper, and blank postcards to make it easier for the prisoners to communicate with the outside.

“I want to give them hope that this horror is not endless,” she said, “and that things will definitely change for the better. I don’t want them to lose hope. It is very easy to fall into despair when you are in prison.”

Although the growing number of repressed people alarms Sannikova, she is heartened by the grassroots movement to support people who are considered political prisoners. The political party Yabloko regularly organizes letter-writing events in cities all over the country. Several former prisoners have taken up the cause of supporting others still behind bars on what are considered politically motivated charges, while quite a few inmates have Telegram and other social media channels that provide information about them and about how to contact them.

“All this is the work of volunteers who are sympathetic,” she said. “And that is a reason for hope. Such solidarity is itself valuable and, what’s more, it is the promise of change for the better.”

Written by RFE/RL’s Robert Coalson based on reporting by correspondent Andrei Filimonov of RFE/RL’s Siberia.Realities.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.