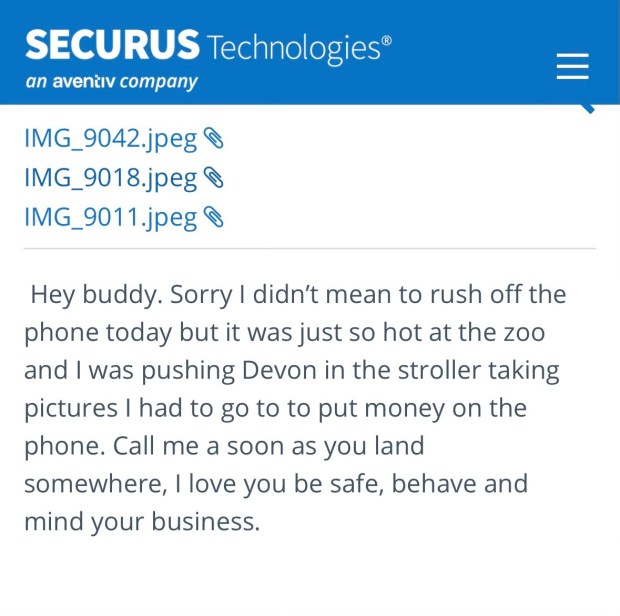

Maria Valdivieso likes to send her incarcerated son photos of his two-year-old son, who she watches over while he’s in prison.

“I love you[. B]e safe, behave and mind your business,” Valdivieso said in a message containing photos of the boy feeding a giraffe at the zoo.

“It was a big milestone for my grandson because he has autism,” she told the Orlando Sentinel. “But I had to carefully select which pictures I wanted to send.”

That’s because she could only afford to send three.

Phone calls, messages and the sharing of media, all of which are subject to costs and fees, are part of her weekly budget in addition to transferring about $50 a week so her son can buy things like toothpaste and soup. Every $50 transfer is charged an additional $8.95 processing fee by the prison banking service company Jpay.

(Handout)

A message by Maria Valdivieso to her son in Florida prison.

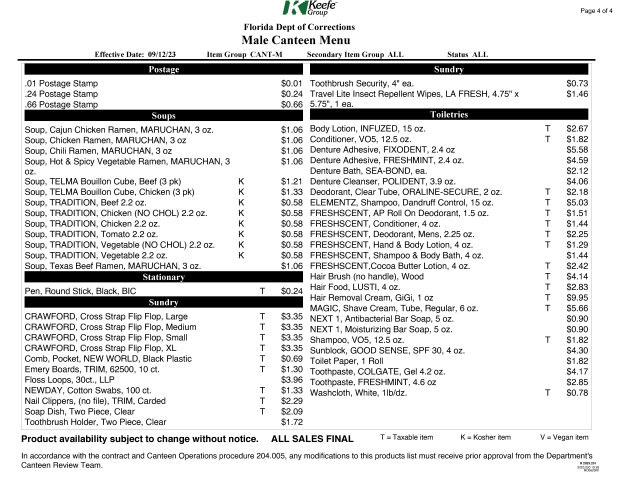

In August, things got more expensive for Valdivieso when a new contract between the Florida Department of Corrections and Keefe Commissary Network increased the costs of snack food and toiletries sold inside prisons.

Male menu commissary items increased by as much as 80%, according to an analysis by the Orlando Sentinel.

Since then, Valdivieso said her 22-year-old son is communicating less, eating less and getting less of the things he may need. He’s been imprisoned in the state since 2020 and is returning home next year.

“Money does not go far anymore,” she said. “Everything has gotten so extremely expensive.”

(Handout)

Maria Valdivieso sent her incarcerated son photos of his two-year-old feeding a giraffe at the zoo. (Courtesy photo)

People who are incarcerated in the state of Florida have to contend with prices set by canteen operators under contract with FDC, and because a majority of them do not earn salaries, people advocating for prison reform say higher rates tend to disproportionately hurt low-income households.

“Across the country we see prisons using commissaries and communication systems and other services that are offered to incarcerated people as a means of squeezing money out of the poorest of families,” said Wanda Bertram, a spokesperson at the Prison Policy Initiative. “These are people who are already struggling, people who are one lost paycheck away from bankruptcy or people who cannot handle a medical emergency.”

Paul Walker, a spokesperson for the Florida Department of Corrections said prices in the new commissary menus and order forms are the result of negotiations, nationwide inflation and efforts to provide a variety of products.

“While FDC was able to limit price increases over the past couple of years, the nation has experienced record inflation over the same time,” he said in an email.

He added that Keefe Commissary Network provided pricing relative to the cost of supplying and maintaining the inventory in prisons across Florida.

FDC did not provide the Orlando Sentinel with a requested copy of the fair market value analysis report that Keefe Commissary Network is contractually required to prepare for the department. Representatives with Keefe did not respond to a request for an interview.

‘How is that fair market?’

Similarly to people outside prison, people who are incarcerated can buy things like food, over-the-counter medicine and hygiene products. But unlike the outside world, price competition does not exist inside prison. Instead, the value of goods is determined by the contractor and signed off by the Florida Department of Corrections.

The Sentinel found more than 60% of the items sold in the male canteen menu went up in price as a result of the new contract.

Four ounces of saltine crackers used to cost $1.16; now they cost $2.80. The Big AZ frozen sandwiches found in gas station convenience stores, a staple inside many Florida prisons, went up by roughly 30%. And a pack of 100 cotton swabs costs $1.33, up from 78 cents.

About 25% of the items went down in price and less than 15% of items cost the same.

“We can go buy a 40-pack of water from Walmart for $5.36, but [FDC] decides to sell [a single bottle of] water for $1-plus,” said author Walter Dunn, a formerly incarcerated man who overturned his sentence after nine years in state prison. “How is that a fair market?”

Food purchased from the commissary can cost more than double the price for similar items sold by large retailers that tend to sell items at a cost-saving volume.

Under the new contract, a bottle of water costs more than seven times the average wholesale price in 2021, according to the Beverage Marketing Corporation.

In Florida prisons, one roll of toilet paper costs an incarcerated person $1.82. As of Wednesday, a pack of a dozen Scott Brand toilet paper rolls costs $10.68, or 89 cents per roll, on Walmart’s online retail store.

Two caplets of extra strength Tylenol costs $1.24 inside a Florida prison. Walgreen’s online store sells 100 caplets for about 14 cents each.

At a senate committee meeting Wednesday, FDC Secretary Ricky Dixon said he doesn’t disagree with the outcry about the prices.

He told legislators on the Appropriations Committee on Criminal and Civil Justice that FDC is working with the vendor to lower the costs of certain items like water and ramen.

The department is also reevaluating limits to the amount of money a person who is incarcerated can receive, capped at $100 a week.

“No one claims, the vendor or us, that we compete with Walmart or Walgreens,” he told legislators. He said canteen operations run similarly to gas station convenience stores where there is a premium added to the value of goods.

“But I don’t want to be dismissive to all the complaints because they do appear to be priced high,” he said.

‘This is a lucrative business’

Sarah Couture, state director and senior research strategist at the Fines and Fees Justice Center in Tampa, said the average grocery store markup in the U.S. is between 1% and 3%.

“It’s insane the markups when it comes to prisons and jails,” Couture said. “Using that chicken ramen example from Walmart, it is 2.53 times more expensive in Florida prisons at $1.06 than what we’re paying. That’s not inflation.”

In August, the Consumer Price Index for grocery store food was 3% higher than last year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Food-at-home prices increased by 11.4% in 2022 and are expected to grow this year but at a slower rate.

Provisions in the previous contract already allowed the commissary contractor to raise prices up to 10% every year. People familiar with canteen prices inside Florida prisons say they did increase annually.

An analysis of canteen prices between 2013 and 2023 shows the cost of toothpaste, tampons, certain frozen sandwiches and pain relief pills have steadily increased over the last ten years.

“From a business perspective you can see this is a lucrative business,” Couture said. “Somebody figured out this could be a revenue stream, so that’s what they did. They went and talked to legislators and the local level politicians and said, ‘Let me take this off your hands, we’ll run this for you,’ and then they jacked up the prices.”

In the new contract, Keefe Commissary Network could request to increase prices every six months by no more than 10%. An exemption clause allows the vendor to increase prices by more than 10% if the contractor can provide documentation of “extreme and unforeseeable market volatility,” among other requirements.

The contractor will compensate the department at the commission rate of 35.6% under the new contract.

During the fiscal year of 2021, FDC made about $26.8 million. The previous commission rate was slightly above 20% of all gross sales, according to a prior contract with Trinity Services Group, which is owned by the same company as Keefe Group.

In fiscal year 2022, FDC made about $28.3 million off commissary commissions.

Revenue generated from canteen sales goes into the recently expanded Inmate Welfare Trust Fund, which is meant to be used to fund things like educational programs.

But Denise Rock, the executive director of the prisoner advocacy group Florida Cares, said she worries the system is broken.

She said she has concerns that the money generated off of canteen sales and telephone commissions, paid by the incarcerated population and their families, will be used to supplement operating expenses and maintenance costs instead of being spent on things like school supplies.

She points to the recent canteen contract which includes value-added services for things like installing 92 recreation yard pavilions and outfitting vending machines with ID scanners.

“All these value-added services are great, but it doesn’t belong in a canteen contract,” she said. “It’s getting paid for with our money. It does not feel fair we don’t have a say in how the money is spent.”

‘We ain’t paying no more’

When a majority of the commissary prices increased more than 10% in August, the department faced an onslaught of criticism from families of people who are incarcerated, prison reform groups and prisoners who lost their ability to afford items they deem essential, like shower sandals.

Dunn said commissary items help supplement a lack of appetizing food and hygienic products issued by the state.

“Hygiene products offered at commissary are a necessity,” he emphasized. “The toothpaste and soap the prison is offering are not adequate.”

He called the markups “astronomical” for people in prison who are likely not earning salaries.

In Florida, only 2% of the prison population, or about 1,700 workers, are paid by the self-funded nonprofit PRIDE Enterprises, which runs work programs in the state system. Those who are paid earn less than a dollar per hour, according to a 2022 report by the ACLU and the Global Human Rights Clinic of the University of Chicago Law School.

When people serving time in prison learned of the new contract, they revolted, with a plan to boycott the price increases.

A message shared within prisons read: “No one goes to the canteen for anything NO ONE. Like straight up forbidden. This is statewide.”

In a video shared with the Sentinel, a detained man participating in the boycott called attention to the price of one packet of ramen.

In Florida, ramen increased 25% to $1.06. In Texas prisons, a packet of low sodium ramen noodles costs 35 cents. “But in Florida we paying extra,” the man said in the video. “We ain’t paying no more.”

The Florida Department of Corrections did not respond to a request to comment on the boycotts.

Staple items more expensive in Florida

Compared to three other state correctional departments, prices for staple items like instant ramen noodles, coffee and water bottles are for the most part cheaper than in Florida’s correctional system.

In Illinois and Texas, bottles of water and packets of ramen at state-run correctional institutions can be purchased for less than 35 cents and more than four ounces of instant coffee ranges between $1.40 and $4.50.

The correctional departments in both states said the agencies contract with multiple canteen operators.

Nevada, which exclusively uses Keefe Group, sells a packet of ramen for 67 cents and four ounces of instant coffee costs $4.32. Bottled water costs $1.87, the highest amount for bottled water among the four states.

Meanwhile, inside Florida’s prisons, a packet of ramen costs $1.06, a bottle of water costs $1.15 and four ounces of instant coffee costs $6.99.

Amy McCourt said both she and her incarcerated boyfriend are struggling to adjust to the new price changes.

She said her boyfriend is prioritizing buying hygiene products before anything else.

There will be days he cannot afford to buy canteen food when chow hall portions are too small or unappealing for him.

“There have been financial times where I’ve been able to send him the max per week so $400 a month. We’re not in that financial situation right now,” she said. “He’s been hit on both ends. He’s getting a reduction in his income, so to speak, and also getting hit with price increases.”

Rock sees the markups as a blow to the local economies where people with incarcerated loved ones live.

“When we go back home we don’t go out to dinner or spend money on a haircut,” she said. “We can’t afford it.”

arabines@orlandosentinel.com

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.