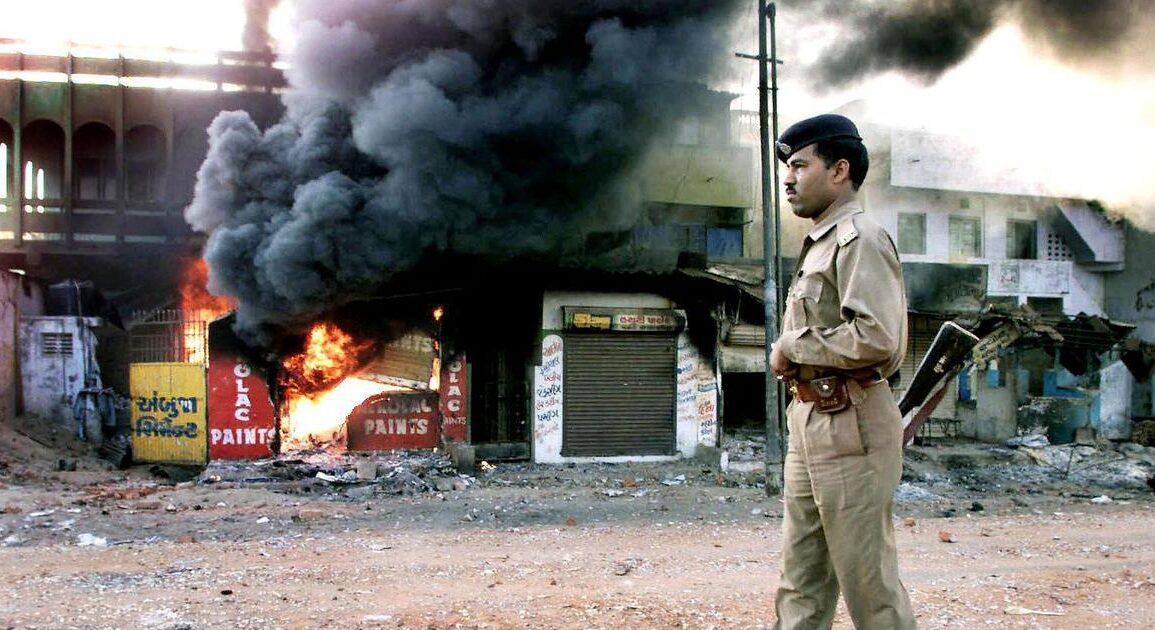

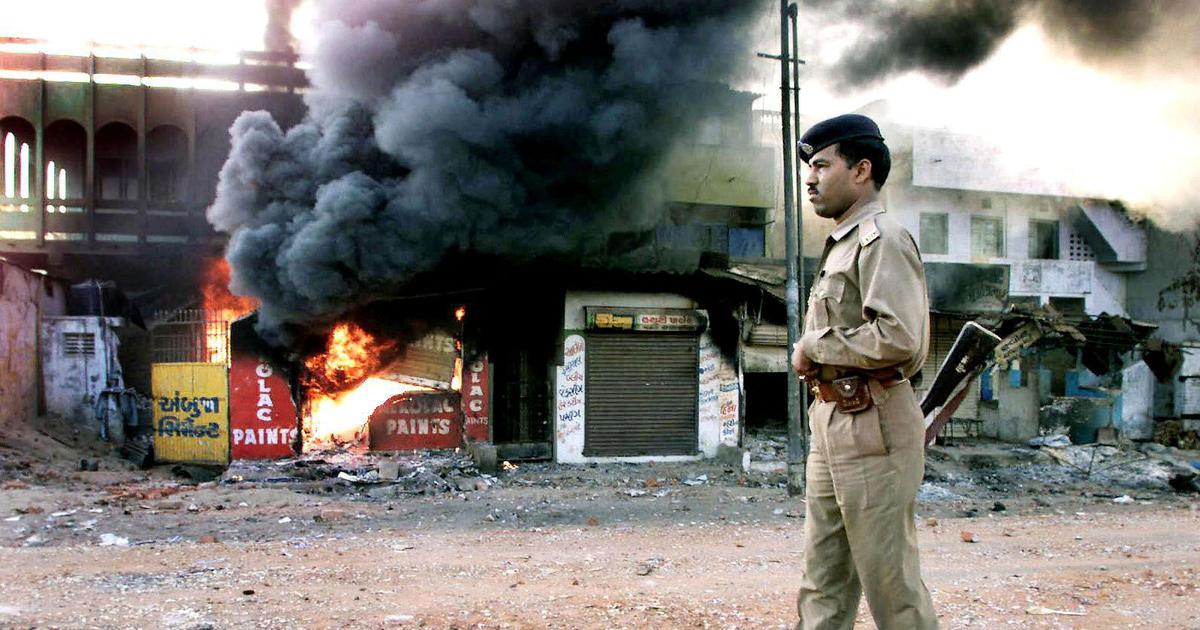

A policeman looks on as a row of shops burns in Ahmedabad on March 1, 2002.

|

AFP

The violence in Manipur has continued for more than two months, leaving in its trail largescale death, destruction and displacement. Several reports of sexual violence have emerged this week. While it is crucial to do everything to stop the violence and provide relief to victims, ensuring accountability for the crimes should be equally high on the agenda.

If India lets go of the opportunity to independently investigate and prosecute this latest outbreak of mass violence, history will be destined to repeat itself. This will only reinforce India’s blemished record of frequent mass atrocities, especially against vulnerable communities, and of the weakened rule of law and democracy.

The toll in the ethnic violence in Manipur has been high. The state government, in its filing before the Supreme Court on July 10, said that 142 people had been killed, while 17 were missing as of July 4. There had also been 5,053 cases of arson – burning of houses and businesses, sometimes of entire villages.

The report also confirmed that 54,488 persons are housed in 354 relief camps. Media and civil society reports say more than 150 people have been killed in the clashes so far and more than 60,000 displaced.

The reports of assaults on women, including rape, have prompted fears that sexual violence has been used as a weapon. Widespread arson and the destruction of churches has been reported. The violence has also affected education – schools in some areas are only now reopening while public services remain crippled.

What stands out in the violence has been the role of individuals and groups in instigating and perpetrating attacks. State authorities – politicians and officials, including the police and security forces – have been accused of failures of commission and omission, and of bias, resulting in the persisting violence and the human toll.

Two months of violence, no resolution

What is known of criminal proceedings, to investigate and fix blame, as a precursor to justice and accountability?

On June 4, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs was reported to be setting up a three-member judicial commission, headed by a retired judge of the Guwahati High Court, to investigate “the causes of the violence and identify those responsible for it”. This followed Home Minister Amit Shah’s announcement in Manipur to restore peace that also included forming an all-community peace committee, which has, from all accounts, been a non-starter so far.

Established under the National Commission of Inquiry Act, 1952, the panel will have only a recommending role and its findings will not be binding on a court of law. Experience shows that the performance of these bodies on their truth-seeking mandate, too, can be patchy. Observers have noted how the hope for accountability in Manipur lies first in effective working of the criminal justice system itself.

The state government’s submission before the Supreme Court says that 5,995 first information reports have been registered and 181 people arrested, besides 6,745 detained as part of the investigations. It is not clear how these investigations have progressed.

What is clear, however, is that authorities have also been registering criminal cases, not just against Kuki scholars, politicians and activists who have been speaking to the press about the violence and complicity of state actors, but also against civil liberties groups that have conducted fact-finding missions. This crackdown on any opinion and expression that is directed against the authorities, bodes ill for the progress of investigation into the violence and for justice.

Shah has also announced the transfer of six “important” cases, to the Central Bureau of Investigation, to probe with “independence and transparency”. The agency handling investigations is no guarantee of independence and transparency, given the controversies surrounding the central agency. Since these cases were identified by the state government, already accused of bias by victims and civil society, independence seems further moot.

Victim groups have approached the Supreme Court, but so far, there is no indication that the court is willing to push for a greater scrutiny of the claims made by state authorities on criminal proceedings, rather than limiting its role to ensuring the restoration of peace and the rehabilitation of victims. The violence and incitement to further violence continues.

Not learning from history

Seeking to stop bloodshed and restore peace without identifying the causes of the violence – and especially holding to account those responsible – risks repeating the mistakes of the past. There is no justice for victims while impunity is reinforced, perpetuating violence in turn.

The 1992 Naga-Kuki clashes in Manipur that left death, destruction, and permanent social fissures, still awaits justice and accountability, as do the Kuki-Paite clashes of 1997. The complete silence of state authorities and civil society on justice for the victims and accountability for the mass violence is as telling as it is constitutive of further conflict and instability in the region.

Neighbouring Assam has its own history of silences and erasures, such the Nellie massacres, where, over the course of just six hours on February 18, 1983, close to 2,000 Bengali-speaking Muslims – according to official count – were killed by youth activists and local villagers.

The findings of a commission of inquiry that exonerated state authorities resulted in the failure to prosecute even those identified, and culminated in a de facto amnesty for all responsible, in negotiations between the central government and Assamese nationalist groups that led to the Assam Accord in 1985.

It is such impunity that created the grounds for the cycles of violence to follow in Assam, in 2012 in Kokrajhar when violence between Bodos and Muslims killed over 100 people, and in Baksa in 2014 when Bodo militants shot dead 30 people

There was some progress on accountability for state violence in the region when the Supreme Court in 2017 ordered an investigation into and prosecution of cases of extrajudicial killings in Manipur. But that hope may be fleeting with victims yet to see concrete justice despite the passage of 12 years since the court’s first ruling.

The lack of accountability for mass violence is, of course, not a Manipur problem, or one just of the North East. Over the history of independent India, the victims of multiple instances of mass violence are yet to see justice.

History of riots, killings

Among the major ones are the anti-Sikh pogrom in Delhi in 1984 in which over 2,700 were killed, the anti-Muslim atrocities in Uttar Pradesh’s Malliana in 1987 when 68 were killed and the riots in Bhagalpur in Bihar in 1989 when more than 1000).

Then there were the Bombay riots of 1992-’93, after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, in which over 900 people were killed. The anti-Muslim pogrom in Gujarat in 2002 recorded more than 1,000 killings. More recently, the Muzaffarangar riots in Uttar Pradesh in 2013 saw 58 killed and the Delhi riots in 2020 in which 68 were killed.

There was also the anti-Christian violence in Odisha’s Kandamahal in 2007 in which over 100 were killed. Besides these there have been several other episodes, big and small, over the past decades, too many to name, that all await truth-telling and justice while their perpetrators suffer no consequence.

This is also the situation of the victims of state violence in Kashmir and Adivasis in central India. Despite laws passed to specifically check violence against Dalits and their persecution, there have been waves of mass atrocities against Dalits and other poorer sections in Bihar in the 1990s. In these instances, too, there has been no justice for the victims nor the perpetrators being held accountable.

Diluting accountability

Instead, there is a growing trend to further dilute accountability. In Uttar Pradesh, cases against the accused in the 2013 Muzaffarangar riots are being withdrawn.

In the Delhi riots, victims have fought an uphill and largely unsuccessful battle, with the police and prosecution, courts and National Human Rights Commission, to register and investigate cases.

Those already convicted of serious crimes in past episodes of atrocities are granted remissions while victims and human rights advocates seeking justice are penalised, effectively criminalising the survivors’ demands for justice and accountability. It is but evident that the absence of accountability breeds impunity.

Paper tigers

What are the provisions in Indian law on accountability?

The main tools for accountability against crimes, including mass violence, are the Indian Penal Code, 1860, and the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, besides special statutes and case laws – such as the Prevention of Atrocities against Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribe Act, 1989, the Supreme Court’s 2018 judgement on mob lynching and the 1996 DK Basu judgement on custodial violence.

The National Human Rights Commission is also empowered to investigate abuses while the Supreme Court and High Courts have writ jurisdiction to hear matters of human rights violations, justice and accountability. There are also public interest litigations.

At the same time, a plethora of laws exists alongside that undercut accountability. For instance, Section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, pertaining to the prosecution of judges and public servants, makes it difficult to prosecute public servants. This is made more difficult due to Article 311 of the Constitution, which set out a rigorous procedure to penalise or dismiss civil servants.

Section 46 (2) of Code of Criminal Procedure provides special powers to police officials to use force if an accused resists arrest. There are also laws such as the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 1958, which provides an effective carte blanche to security forces in “conflict zones” to use force. These provisions have shielded state officials accused of abuses, against accountability. The higher courts have, controversially, upheld these provisions.

International conventions and norms on justice and accountability find a cold reception in India, despite its claims to being committed to these ideals. New Delhi has not ratified or accepted several relevant mechanisms, including the Torture Convention, Convention on Enforced Disappearances and the Additional Protocol I and II of the Geneva Convention to protect the victims of non-international armed conflicts. The Optional Protocol of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which offers a for the redressal of human rights violations, has not been ratified either.

While India has ratified the Genocide Convention, it did so with reservations. Genocide is also not defined in Indian law, in effect preventing the identification and prosecution of crimes defined in the convention, including the crime of incitement to genocide.

India is also not a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, set up to prosecute atrocity crimes, including genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The country has instead questioned the legitimacy of the International Criminal Court, and contests developments in international law on the prevention and prosecution of crimes against humanity.

Weak regime, no accountability

A weak domestic regime on accountability against mass violence and a poor record on engaging and adopting the international regimes encourages impunity, especially in instances of mass atrocities, with telling consequences.

India consistently ranks among high-risk countries in the Early Warning Project’s Statistical Risk Assessment of mass violence and genocide, and has several cases marked for Genocide Alerts.

It is crucial to break this vicious cycle of impunity and mass violence. The tragic developments in Manipur provide an opportunity that India must seize to chart a new path.

This should begin with an independent investigation into the atrocities in the state and speedy prosecution of the accused. The July 13 resolution by the European Parliament on the violence in Manipur provides an opportunity to make this transparent, by incorporating external observers, as a way to better engage the international regime. In the process, India could play a leadership role, internationally, on truth, justice and accountability for mass atrocities, for other countries to follow.

Sajjad Hassan worked in Manipur for several years, in the Indian Administrative Service, and has studied and published on conflicts and governance in the state and nationally.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.